Mar 2, 2023

Chicago’s Next Mayor Must Have a Plan to Tackle the City's $34 Billion in Pension Debt

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Chicago is guaranteed a new mayor after voters rejected incumbent Lori Lightfoot’s bid for a second term. With the looming leadership change, investors want to know whether the city will keep up recent financial momentum or return to old bad habits.

The third-largest US city escaped from junk-rating territory late last year after paying more into its long-strained pensions that are still short nearly $34 billion. The mayoral runoff contenders — Cook County Board Commissioner Brandon Johnson and Paul Vallas, the former Chicago schools chief, have starkly different approaches for how to address that shortfall and the rest of the challenges facing its 2.7 million residents.

“Preserving and furthering the financial and credit improvements should be a top priority for any candidate,” said Dora Lee, director of research at Belle Haven Investments, which holds Chicago debt as part of $15 billion in muni assets. “Campaign promises are very easy to make but very hard to execute. However, they will be easier to accomplish if the city is on a sound financial footing.”

The city has long struggled with pension debt and chronic structural deficits. With about one out of every five budget dollars going to pensions, there’s less money available for crucial services like policing. This comes as the city struggles with rising crime, a key issue that contributed to Lightfoot’s loss. Both Vallas and Johnson have promised to make the city safer and more equitable for residents but differ on how to fund their plans.

Johnson, who is backed by the Chicago Teachers Union, and Vallas, who is endorsed by the police union, have laid out high-level plans. Neither were immediately available for an interview.

According to his campaign website, Johnson, 46 wants to raise taxes on companies that profit from doing business in the city, including hotels, and airlines that pollute the city’s air. He would reinstate the so-called “big business head tax” with a $4 per employee levy on companies that perform 50% or more of their work in Chicago. He’s also proposing a “mansions tax” on the transfer of high-value properties and a levy on securities trading, which the city’s exchanges have opposed.

Vallas, 69, the front-runner who won nearly 34% of the Feb. 28 vote compared to Johnson’s 20%, has an entire page on his campaign website devoted to pension funding. He would put the city’s retirement funds under the direction of independent professional investment managers who are held accountable for performance. His plan also leans heavily on working with state officials to secure more funding.

Vallas also would consider tapping surpluses from tax increment financing districts to fund pension obligation bonds, according to his campaign website.

One major point of agreement: both Vallas and Johnson have said they won’t raise property taxes, a major source of revenue. Roughly 80% of those levies go to pay retirement benefits.

Advanced Payment

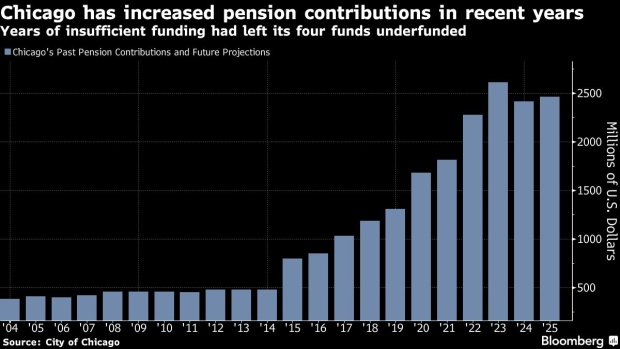

Under Lightfoot, the city boosted payments to its retirement funds by more than a $1 billion in the last three years to meet statutory funding mandates that kicked in before Covid-19 hit. But her administration went further by putting in $242 million more than required in the 2023 budget. It also advanced roughly half a billion dollars to its funds starting in late 2022 to prevent them from selling assets during a market rout.

The increased pension funding led to credit upgrades, including one in November from Moody’s Investors Service that lifted its rating from junk to investment grade for the first time since 2015. The previous month, Fitch Ratings had raised the city’s credit by one level to BBB with a positive outlook.

“While it’s too early to gauge the impact of any new administration’s fiscal policies and financial management, Chicago’s ‘BBB’ rating and positive outlook hinge upon the city sustaining its commitment to maintaining high budget reserves and actuarial pension funding,” Michael Rinaldi, a senior director for Fitch, said in an email.

Chicago is continuing to recover financially from the pandemic, with revenue growing and budget shortfalls shrinking since the worst of 2020 and 2021 partly thanks to to federal aid, according to Sarah Wetmore, acting president of government fiscal watchdog the Civic Federation.

“There are still a number of issues the city faces going forward, including still high levels of violence, a public transit system struggling with reliability issues and decreased ridership as well as substantial projected budget deficits in coming years once federal pandemic funding runs out,” Wetmore said.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.