Apr 27, 2022

Child-Care Workers Are Quitting the Industry for Good in the U.S.

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Low pay, demanding work and a lack of benefits have driven child-care workers out of the industry for good during the pandemic — creating ripple effects on the rest of the U.S. economy.

Employment in daycare services remains more than 10% below pre-Covid levels, compared with just 1% for the labor market at large. LinkedIn data suggest many of these women — early child-care work is almost entirely done by women — moved to other jobs, primarily in education.

Sarah Mallett, 32, is one of them. She worked at an early childhood facility in Maine for almost nine years, struggling to pay her student loans with her hourly wages before ultimately leaving during the pandemic to teach in a public school.

“That was where my heart and soul was,” Mallett said of working with younger kids. “But when we shut down, and we hadn’t been working for three months, that’s when I knew I needed to shift my income and my security and find a way to get benefits.”

Staffing shortages — paired with the thousands of child-care centers that never reopened — leave about 460,000 families struggling to find alternatives, based on Wells Fargo & Co. estimates, keeping some of these parents, especially mothers, out of the labor force. As Wells Fargo economists put it in a note last month: The daycare industry's challenges are making hiring more difficult and expensive for all sectors.

Covid-19 exacerbated pre-existing shortages in an industry known for its high turnover, causing hundreds of thousands of employees to lose their jobs when daycares shut down.

As the economy recovered, the tight labor market pushed employers from retailers to restaurant chains to boost wages to at least $15 an hour, extend benefits coverage and offer job flexibility to lure applicants. The early child-care sector is unable to compete financially. It means that, on average, people who take care of infants and toddlers often make a lot less than those who work at the local store or warehouse.

Providers say they can’t charge parents much more than they already do — households on average spend about 13% of their income on child care in the country. Pandemic relief helped some daycares increase pay temporarily. But without sustained government support, business owners say they can’t afford sustainable wage increases.

“You want to pay people what they should be getting but then at the same time that means you have to charge parents a whole lot more to be able to do that,” said Tieraney Rice, owner of Gilmore Prep Academy, a preschool based in Greer, South Carolina.

The average day-care worker earns about $12.40 an hour — or $25,790 a year, according to May 2021 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s barely above the poverty level for a household of three in the country, according to government data. Across all occupations, the average is $28.01 an hour.

In Maine, where the average hourly wage for child-care workers is below $15, Tara Williams, executive director of the Maine Association for the Education of Young Children, said she’s seen early-childhood educators leave for national chains, convenience stores, hair salons and even to open a photography business.

“We have signs all over at big-box stores, retail, coffee shops, restaurants — everybody’s hiring — and all of the signs are showing $17, $18, $19,” Williams said. “And that often includes starting bonuses, benefits packages.”

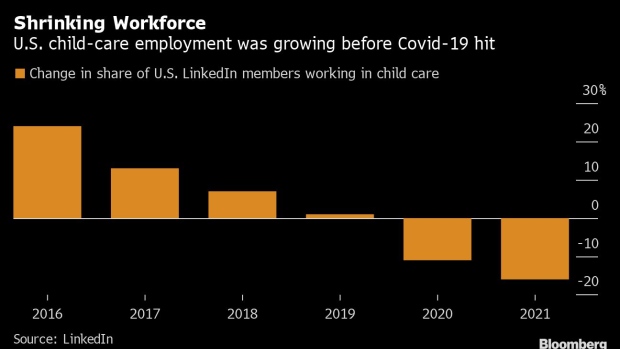

An analysis by LinkedIn found that the share of U.S. users who work in child care shrunk by 11% in 2020 and another 16% in 2021. During the three years that preceded the pandemic, that share had grown — albeit at a declining pace.

Excluding teaching roles, common next roles by people who exit the field include administrative assistants, sales and customer service. Some also took jobs as nurses or receptionists.

The impact on care quality is widespread. Two-thirds of early-childhood educators said staffing shortages are affecting their ability to serve families, according to a survey by the National Association for the Education of Young Children earlier this year.

Advocates point to the need for government funding to help providers increase wages for workers who are often required to have a bachelor’s degree — and sustain their business operations.

The U.S. is an outlier among developed countries, investing relatively little public money into the care of very young children. The largely private system relies instead heavily on families’ spending at a time in their lives and careers when parents often have limited resources, according to a report by the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution.

Although reforming child care generally has bipartisan support, the federal government hasn’t been able to agree to new legislation.

President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which originally included $400 billion for child care and preschool, has been stalled by Democratic Senator Joe Manchin, who has offered a slimmed-down package that wouldn’t include child care.

Republican Senators Tim Scott and Richard Burr introduced a bill on March 22 that would reauthorize the Child Care and Development Block Grant, providing about $6 billion a year to subsidize child care for working families and improve reimbursement rates for businesses so they can recruit and retain staff.

The fate of that bill is still unknown, but if it passes it could expand child-care supply and help cover costs incurred by providers, said Cindy Lehnhoff, director of the National Child Care Association.

“There's no question that this is not a crisis that will get better on its own,” said Charlie Joughin, a spokesperson for the First Five Years Fund, an advocacy group. “The only solution is significant and sustained funding from the federal government.”

Rachel Shelton, a former public school teacher and mother of two in Asheville, North Carolina, was working at the preschool both of her children attended heading into the pandemic. The preschool shut down in March 2020, ultimately closing permanently. Now she’s looking to leave teaching entirely.

“As a society we just haven't valued that work in the way that we do other professionals,” said Shelton, 36. “I’m not looking for jobs in that profession right now, and I wish it were different because I think I’m good at it, and I have good skills.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.