Jun 17, 2021

China growth decouples from credit, with global implications

, Bloomberg News

Why China may feel more strongly about engaging with Russia post-G7

Chinese manufacturer Lou Zhongping is being bombarded with offers of new loans from banks and government officials, attention that he says is finally coming to smaller businesses like his own.

“A lot of financing companies have been contacting us wanting to invest and help us develop more quickly,” said Lou, whose company Soton Daily Necessities Co. Ltd., supplies drinking straws to retailers like Starbucks Corp. “The financing environment is the best it’s ever been.”

Lou’s experience suggests that even though China is putting the brakes on credit expansion in the economy, that doesn’t have to signal slower growth in the economy or demand for commodities. That’s because the traditional link between credit and growth is not as strong as it once was.

Foreign demand is playing a key role in the economy this year as a pandemic-fueled export boom is set to continue. Domestically, more financing is being funneled to private-sector businesses like Lou’s, while service and technology companies -- which require less credit to expand -- make up a bigger portion of the economy.

Some economists argue that credit has even decoupled from investment in the heavily indebted property sector as business models change.

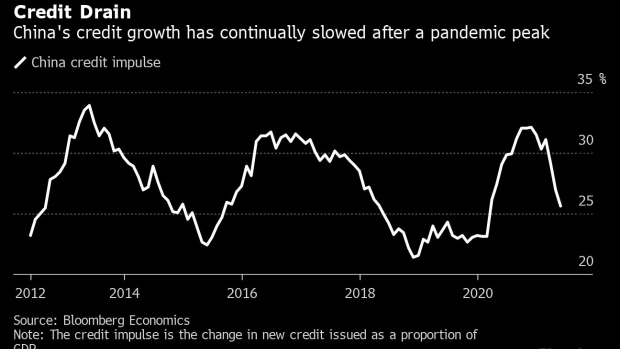

China watchers look at the “credit impulse” -- which measures the growth in new financing as a share of gross domestic product -- as an indicator of business cycles. China’s property developers, manufacturers and local governments depend on new credit for investment, driving up employment and demand for imports of industrial goods and commodities.

That in turn creates a global industrial cycle correlating with everything from Australian GDP to the strength of emerging-market currencies. U.S. Treasury bond yields tend to rise and the S&P 500 falls in tandem with the Chinese indicator.

The credit impulse peaked late last year and has been declining since as Beijing seeks to taper its pandemic stimulus. Here’s a deeper look at why that doesn’t necessarily mean a slowdown in the economy.

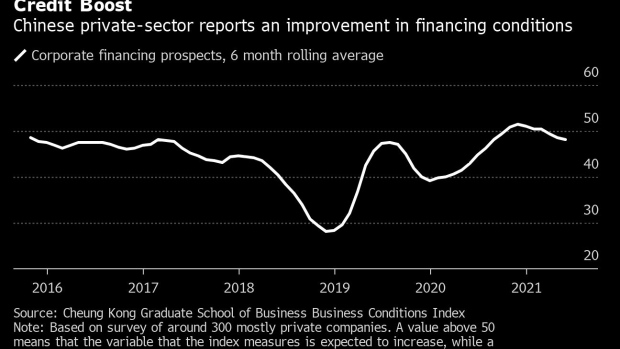

Private Sector

China’s central bank last year provided a surge of funding for banks specifically earmarked for lending to small and medium enterprises. Official and independent data show that has significantly raised the share of credit flowing to such companies.

That matters because privately-owned companies are generally more efficient than state competitors in the same sector, so their investment results in bigger increases to the economy’s productive capacity.

Services and Tech

The economy has shifted over the past decade from a reliance on heavy industry and investment to services and technology, referred to as “new economy” sectors. The share of services in China’s GDP reached nearly 55 per cent last year, up from 45 per cent a decade earlier.

Service companies typically need to spend less on investment in fixed capital like equipment, and there is evidence that, like many other places, the pandemic accelerated a digital shift as more services moved online. The share of economic output that depends on digital technology reached nearly 40 per cent of GDP in 2020, up from about 33 per cent in 2017, according to estimates from Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

“The impact of credit growth on China’s growth cycle has faded in recent years as construction, the most credit intensive sector, is no longer the key source of demand drive,” said Li Cui, chief economist at China Construction Bank International.

“The decline in credit intensity means Chinese commodity demand will change in its mix. Those related to construction, such as steel, will grow modestly but those related to manufacturing upgrading and green economy, such as copper, are still strong,” she added.

Profits and Equity Finance

Chinese companies can also expand in ways that don’t show up in official credit measures: they can issue equity or use retained earnings. Money raised from listing on stock exchanges in China almost doubled last year from the previous year, according to PWC.

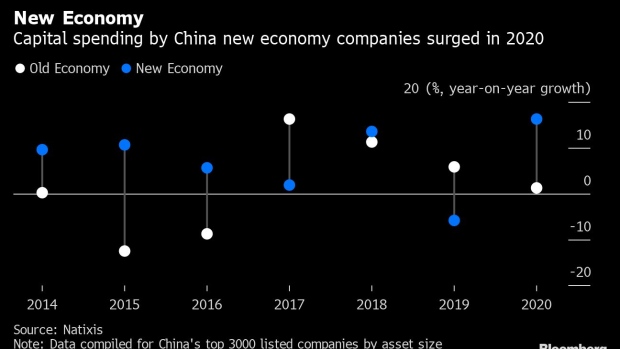

An examination of listed companies shows that those in “new economy” sectors, such as health care, renewable energy and semiconductors, had a smaller decline in income than those in “old economy” sectors like mining infrastructure, materials and real estate during 2020. Profit margins for new economy sectors also increased. That allowed for a 16 per cent surge in capital expenditure among listed new economy companies, according to analysis by Natixis SA.

China’s technology giants illustrate the trend: they are ploughing profits earned last year into expanding their businesses.

“Faster profit growth and lower leverage mean the new economy has larger room to expand capital expenditure than the old sectors,” said Gary Ng, an economist at Natixis. That will help China increase long-run productivity, meaning that “the decline of potential growth in China can be delayed with a higher share of the new economy,” he added.

Venture-capital funding has also risen sharply in China since the second half of last year, which benefits fast-growing companies, like Guiyang-based autonomous driving startup Pix Moving. The company’s founder, Angelo Yu, said “it’s really difficult for early-stage startups like us to apply for a bank loan,” yet the business raised several million dollars from venture capital investors last year.

Property and Savings

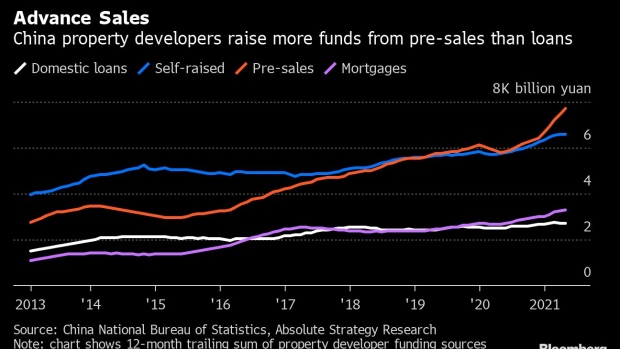

Real estate investment is one of the main drivers of China’s growth and has traditionally been dependent on debt-financing. Beijing has tried to rein in the property market since 2017, concerned that the sector diverts resources away from more productive uses and creates financial risks.

In response, China’s real estate giants have sharply increased their reliance on pre-sales of apartments.

“The link between credit growth and housing starts had already broken,” said Adam Wolfe, China economist at Absolute Strategy Research. “That means the most credit-intensive sector in the economy is less sensitive to the credit cycle.”

Beijing has tightened credit access for property developers even further this year. But that might do little to interrupt sales as wealthier Chinese households amassed extra savings last year as they stayed at home, which remain available to be spent on property.

Local governments also have savings from unspent bond issuance last year, available for spending on commodity-intensive infrastructure projects. And if just a fraction of household savings are spent in the next few months, there could be a noticeable boost to GDP growth, said Freya Beamish, China economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

“In the current circumstances, I’m less worried than normal about slowing credit and money growth,” she said.