Dec 8, 2022

China’s Carbon Market Falls Far Short of Making a Climate Impact

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- More than a year after its launch, China’s national carbon market has failed to force the country’s power companies to slash emissions.

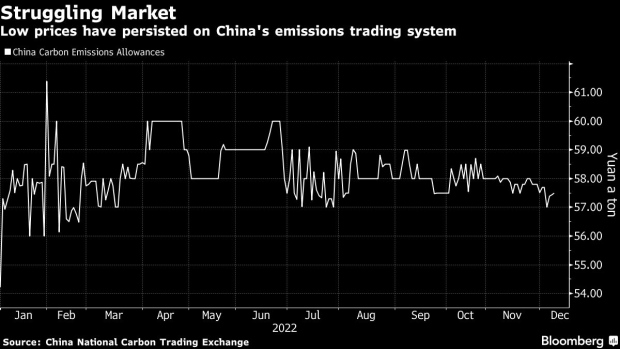

Trading volumes have underwhelmed as narrow participation and outsized allowances keep the price of polluting at a fraction of the more established market in the European Union. And while coal remains at the forefront of China’s electricity generation, utilities don’t have much incentive to limit the amount of carbon they spew into the atmosphere.

The cost to a power firm in China for releasing a ton of carbon dioxide has averaged less than $9 this year. That compares to $85 in the EU. The slow start is a feature of the system rather than a bug: the government has deliberately been generous with its permits, kept prices low, and left out other polluting industries, in order to avoid straining the finances of some of its most important companies.

“We don’t actually see a lot of pressure given the allocation we have and also the pricing point that’s currently there,” Hendrik Rosenthal, director of group sustainability at CLP Holdings Ltd., told the Asia Climate Summit in Singapore on Wednesday. The company, which holds stakes in coal-fired power plants across China, has been more concerned with rising fuel prices, he said.

China is the world’s biggest emitter and the carbon market, launched in July last year on the Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange, should become a prominent tool for fighting climate change at some point. But that’s unlikely to happen until the nation starts cutting coal consumption, which it plans to do from 2025, and adds other dirty sectors like steel and cement. In the meantime, the government is figuring out how to best make it work, including nailing down accurate data on emissions.

Why China’s New Carbon Market Is No Quick Climate Fix: QuickTake

The market has been ineffective because only power companies can trade, according to Qimin Zhang, head of environmental commodities trading for Asia-Pacific at ACT Commodities Group. Adding other sectors would trigger more activity, he said, as would allowing financial investors to participate.

Expansion has been trailed by the environment ministry, which oversees the market, although its plans have been set back by economic concerns because the government is reluctant to add costs to struggling industries. Deepening trade by adding derivatives has also been proposed.

“The most effective way and the easiest way to increase liquidity, in addition to adding more sectors, is opening the door to investors,” Zhang said. “All the trading firms, like us, should be allowed to enter. If there are no intermediaries in the market, there will be no liquidity.”

--With assistance from Dan Murtaugh.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.