Apr 12, 2022

China’s Covid Outbreak Highlights Weak Lending as Borrowers Hold Back

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China’s central bank is struggling to drive up lending in the economy despite cutting interest rates and giving banks a cash boost.

With a worsening Covid outbreak locking down mega cities Shanghai and Shenzhen, worries about jobs and incomes mean businesses and consumers are unwilling to take on more debt. Banks are reluctant to extend more loans too as a property downturn drives up bad debts and squeezes profits.

That creates a challenge for the People’s Bank of China, which is set to diverge further with a tightening U.S. Federal Reserve by possibly cutting policy interest rates for a second time this year on Friday. Many economists also expect the central bank to reduce the amount of cash banks must hold in reserve, freeing up more money for lending.

Problem is, with restrictions to contain the spread of omicron amid China’s ongoing Covid Zero strategy keeping consumers on edge, any new stimulus may end up being parked at banks rather than flowing through to the real economy.

“Credit demand is so weak, but there is abundant liquidity in the interbank market and the banks are having trouble lending them out,” said Helen Qiao, chief China economist at Bank of America. Since credit demand is very low, adjusting interest rates and cutting reserves isn’t the most effective form of monetary policy for China, she said.

With monetary policies in the world’s two biggest economies now headed in opposite directions, the traditional premium Chinese debt returns compared with U.S. Treasuries vanished for the first time since 2010. That may constrain the PBOC’s policy options, for fears too much easing would spur money to shift out of the nation’s markets.

China’s leaders in early March set an ambitious GDP growth target of around 5.5% for the year. Since then, the war in Ukraine has pushed up energy costs, and virus outbreaks and shutdowns to contain infections have caused economists to cut their forecasts. The State Council, China’s cabinet, has also pledged additional support.

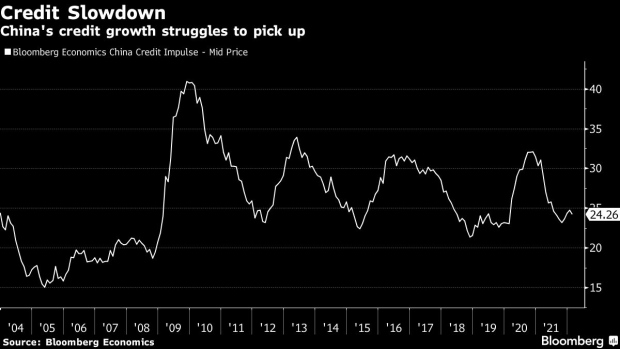

Despite two reductions last year in the reserve requirement ratio -- the level of deposits lenders must lock away at the central bank -- and an interest-rate cut in January, China’s credit impulse, a measure of the ratio of new credit to gross domestic product, decelerated sharply in 2021 and has yet to pick up significantly.

Latest figures show a pickup in credit in March, largely due to a ramp up in bond sales from local governments and a seasonal boost as companies accelerated borrowing after the Lunar New Year holiday. But mortgage growth and long-term corporate loans remained weak, suggesting ongoing caution.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say...

Monetary policy transmission is a key issue for almost all central banks. The better the transmission is, the more willing the central bank would be to ease policy when necessary.

The demand in private sector in China has been weaker than before. It is a hurdle for the PBOC to maintain credit expansion.

David Qu, China economist

The central bank has acknowledged it has a problem. At the end of March, the monetary policy committee promised to “unclog” the transmission system, the first time since late 2020 it’s referred to the issue.

For Xu Gao, chief economist at Bank of China International, the key to getting credit flowing again lies in the property market, which remains under strain after Beijing tightened restrictions last year to curb runaway prices and debt.

“The core problem is a lack of confidence,” he said. “Even if banks lowered mortgages rates, residents still don’t dare to buy houses and take on mortgages because they fear the buildings won’t be finished and delivered.”

Signs of weak lending are everywhere.

Even though the average corporate loan rate trended lower last year, the growth of new medium and long-term corporate loans -- reflecting companies’ fixed-asset investment demand -- slowed in the first three months of this year from last year. Long-term household loans, a proxy for mortgages, shrank for the first time ever in February and remain below the levels reached in previous years.

And rather than a lack of liquidity, banks are actually flush with cash. The rate on one-year interbank loans has been below the policy interest rate on the one-year medium-term lending facility since mid-2021, implying that it’s cheaper for banks to borrow from each other than to take out low-cost loans from the PBOC.

Even with all that cash sloshing around, banks are saddled with low profitability and rising debt though, making them less willing to give out loans.

John Beirne, vice chair of research at Asian Development Bank Institute, said interest rate cuts from the central bank reduce the net interest margins for banks, and combined with high levels of risk aversion and fears of taking on more debt, rate cuts may not be passed through to borrowers.

The amount of bad loans rose to 2.85 trillion yuan in the fourth quarter of last year, up around 18% from two years ago before the pandemic, according to figures from the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission. Even though the non-performing loan ratio declined to 1.73% in the October-December period from a recent peak of 1.96% in 2020, it was still well above the level of around 1% a decade ago.

The situation is likely worse at smaller banks. Net income at Guangzhou Rural Commercial Bank Co., for instance, plunged 28.4% last year, mainly because it made more provisions for asset impairment losses to “enhance its ability to resist risks under the complex external environment and the epidemic,” the lender said in its annual report. Credit impairment losses surged nearly 60% last year to 12.5 billion yuan ($2 billion), it said.

A weaker monetary policy transmission means the PBOC may opt for only a small rate cut, a move that would be more about signaling supportive policy, said Jing Sima, a China strategist at BCA Research Inc.

“Our view is that the PBOC has done its job,” she said. “More rate cuts won’t do much to boost the real economy.”

Rather it’s regulatory policies that are preventing central bank measures from being more effective, she said. Strict financing rules imposed on the property sector, tighter regulation of the Internet sector and Covid Zero controls have all hurt private sector sentiment and borrowing demand, she added.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.