Dec 17, 2018

China's ground zero for billionaire tycoons faces new risks in Trump era

, Bloomberg News

Shenzhen, ground zero for China’s economic opening, has never had it better. But the glittering megacity is also poised to face a string of new threats in an era of increasingly contentious international relations.

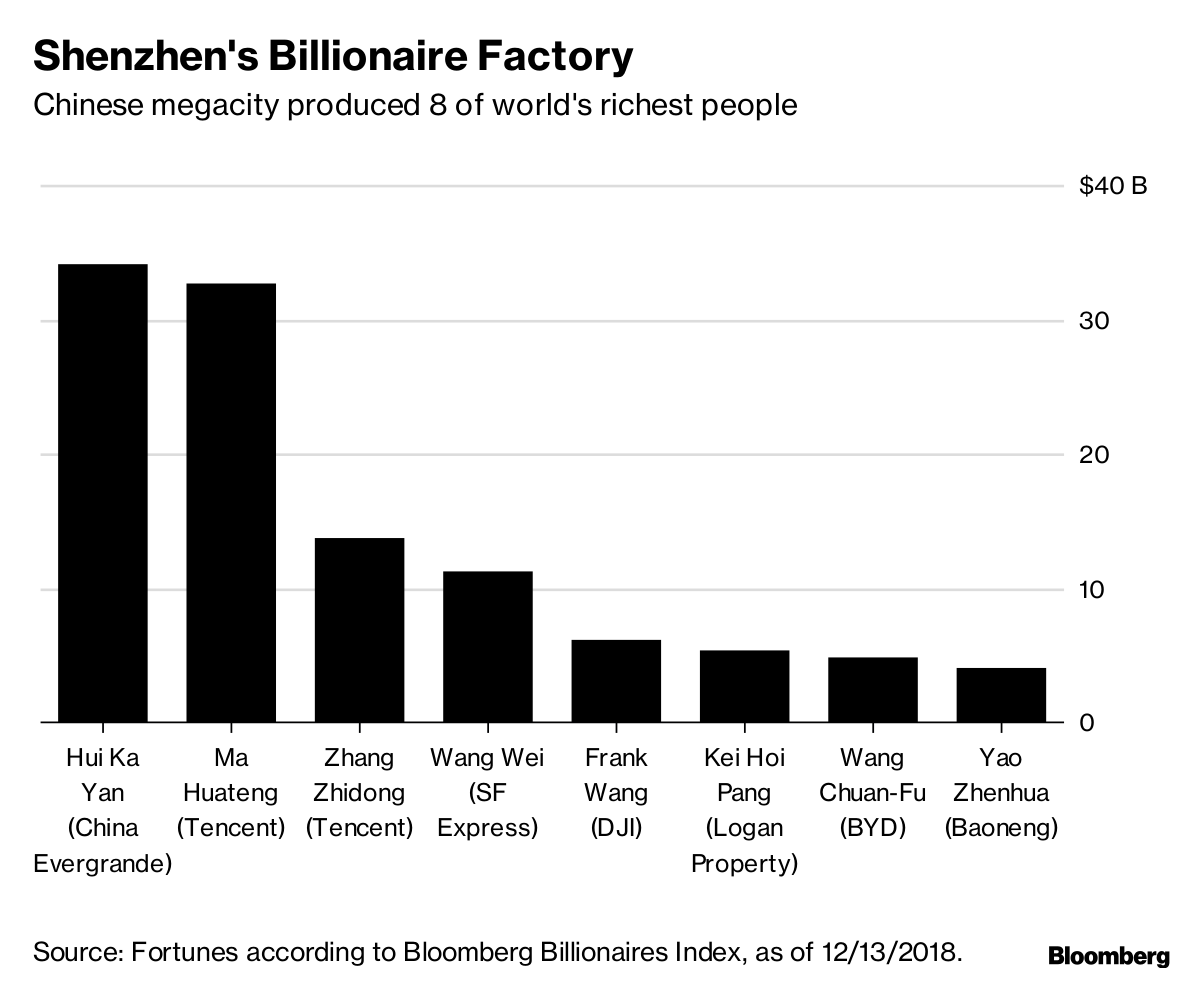

The Chinese city, in the Pearl River Delta north of Hong Kong, will feature celebrations this week of the 40th anniversary of economic reforms that spurred astonishing growth for China. The great opening up, as it’s known, transformed a village of fishermen and rice farmers into a thriving metropolitan area, home to hundreds of companies, including eight controlled by tycoons who are among the world’s 500 wealthiest people and together worth US$110 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

They include Tencent Holdings Ltd.’s (TCEHY.PK) Pony Ma and Wang Chuan-fu, who started BYD Co. (BYDDY.PK), which produces more electric vehicles than Tesla Inc. (TSLA.O). And they are among the powerful across China who must steer their businesses through new challenges. The tariffs U.S. President Donald Trump imposed on Chinese goods are weighing on the whole country’s economy.

Chinese stocks dropped earlier this month after Meng Wanzhou, chief financial officer of Shenzhen-based Huawei Technologies Co. and daughter of the telecom giant’s billionaire founder, was arrested in Canada on Dec. 1 at the request of the U.S., which has accused her of violating sanctions on Iran. The technology-heavy Shenzhen Composite Index is down about 30 per cent for the year, heading for its worst performance since 2011.

“The entrepreneurs in Shenzhen and other places face heavy headwinds in the next few years,” said Liu Jing, professor of accounting and finance at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in Beijing. “They face a possibility that the global markets will no longer remain open and there’ll be insufficient domestic demand.”

That’s not to say that Shenzhen hasn’t been booming as it produces everything from air-conditioning units to smartphones. Its gross domestic product is projected to reach US$350 billion in 2018.

But many of the city’s tycoons have already been hit, to one degree or another, by the 2018 “wealth rout” in Chinese internet stocks that was driven by the Trump trade war, weakening advertising revenue for online businesses and worries over a slowdown in economic growth, said Chelsey Tam, an analyst at Morningstar Investment Service.

The Chinese tycoons are also under pressure at home, from the new emphasis of President Xi Jinping’s government on equality and from new tax policies that threaten to put the rich, and their businesses, under the microscope.

While the Communist Party still backs private business and entrepreneurs as drivers of economic growth, it seems to have a new attitude toward personal wealth and the problem of income inequality. It has cut taxes on lower-earning citizens while pushing up levies on property and other assets to increase the burden on the most affluent.

Many of those are based in Shenzhen, the city most emblematic of China’s dramatic ascent. After it become the country’s first special economic zones in 1980, ruled by more market oriented policies that were radical at the time, foreign investment poured in, attracted by tax and other incentives.

Shenzhen was tapped by Deng Xiaoping, who on Dec. 18, 1978, consolidated his power after Mao Zedong’s death during a meeting of Community Party leaders. That set the stage for the shift to a more market-friendly economy.

Shenzhen exploded — its population went from around 30,000 to more than 12 million in less than four decades — and helped create the new China. “Shenzhen has given us a great push in terms of innovation and a great stage to develop,” BYD’s Wang said in an interview earlier this year.

Among the city’s first tycoons was Yuan Geng, a former guerrilla fighter and adviser to Vietnam’s rebel leader Ho Chi Minh. As an envoy of China’s transport minister, Yuan drew up reports in the 1970s for party leaders that called for the creation of the economic zone. He later headed a unit of the conglomerate China Merchants Group, which developed ports and construction zones there.

Yuan died in 2016 at the age of 99, without ever becoming a billionaire. But he may have helped draw the blueprints for China’s global ambitions. The China Merchants Group in 2013 bought a stake in a port in Djibouti, and the company’s website says it plans to export to Africa the development model that Yuan pioneered in Shenzhen’s ports.

Meanwhile, a statue of Yuan was unveiled last year in Shenzhen. It’s located next to a vast shopping center and entertainment complex known for foreign eateries, western bars and a hotel shaped like a giant boat.

With assistance from Venus Feng and Matthew Campbell