Feb 28, 2023

China’s Imports of Russian Uranium Spark Fear of New Arms Race

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- On the same day in December when Chinese and US diplomats said they’d held constructive talks to reduce military tensions, Russian engineers were delivering a massive load of nuclear fuel to a remote island just 220 kilometers (124 miles) off Taiwan’s northern coast.

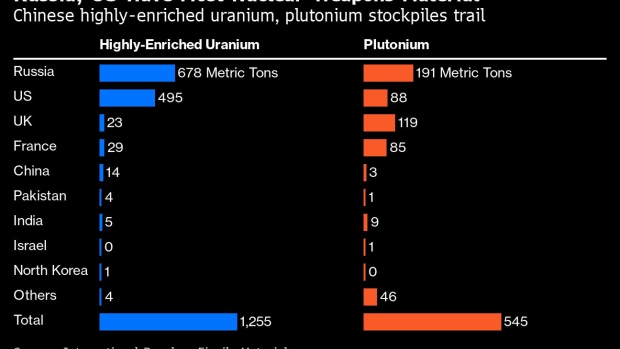

China’s so-called fast-breeder reactor on Changbiao Island is one of the world’s most closely-watched nuclear installations. US intelligence officials forecast that when it begins working this year, the CFR-600 will produce weapons-grade plutonium that could help Beijing increase its stockpile of warheads as much as four-fold in the next 12 years. That would allow China to match the nuclear arsenals currently deployed by the US and Russia.

“It is entirely possible that this breeder program is purely civilian,” said Pavel Podvig, a Geneva-based nuclear analyst with the United Nations’s Institute for Disarmament Research. “One thing that makes me nervous is that China stopped reporting its civilian and separated plutonium stockpiles. It’s not a smoking gun but it’s definitely not a good sign.”

China’s burgeoning capacity to expand its atomic weaponry comes as the last remaining treaty limiting the strategic stockpiles of the US and Russia is on the verge of collapse amid spiraling confrontation over the war in Ukraine. President Vladimir Putin announced Feb. 21 that Russia is suspending its involvement in the New START agreement, a decision US President Joe Biden condemned as a “big mistake.”

In a Dec. 30 videoconference, Putin told Chinese President Xi Jinping that defense and military technology cooperation “has a special place” in their relations.

“Clearly, China is benefiting from Russian support,” said Hanna Notte, a German arms-control expert. The risk for Beijing is the US may expand its own stockpile in response to China’s build-up as well as the Kremlin’s abrogation of arms-control treaties and “the discrepancy will just grow again,” she said.

US Department of Defense officials have repeatedly raised alarm over China’s nuclear-weapons ambitions since issuing a 2021 report to Congress. Military planners assess that the CFR-600 is poised to play a critical role in raising China’s stockpile of warheads to 1,500 by 2035 from an estimated 400 today.

Pentagon officials say Russian state-owned Rosatom Corp.’s Dec. 12 supply of 6,477 kilograms (14,279 pounds) of uranium is fueling an atomic program that could destabilize Asia’s military balance, where there are growing tensions over Taiwan and control of the South China Sea. China possesses few means to increase its plutonium stockpile for nuclear weapons after its original production program closed down in the 1990s, experts say.

China rejects the US’s concerns. The Foreign Ministry in Beijing said China “strictly fulfilled its nuclear non-proliferation obligations” and voluntarily submitted “part of civil nuclear activities” to the International Atomic Energy Agency. Defense Ministry spokesman Tan Kefei said in a Feb. 23 briefing the US repeatedly hyped up the “China nuclear threat” as an excuse to expand its own strategic arsenal, while China maintained a defensive policy that includes no first-use of nuclear weapons.

Why US-Russia ‘New START’ Nuclear Treaty Is in Peril: QuickTake

US protests didn’t dissuade China National Nuclear Corp. from taking delivery of fuel from Rosatom for the CFR-600 reactor, which is based on a Russian design using liquid metal instead of water to moderate operation. Exclusive trade data showing details of the transaction was provided to Bloomberg by the Royal United Services Institute, a London think tank.

The expanding nuclear partnership between Russia and China is having a huge impact on non-proliferation efforts. Between September and December, the RUSI data show Russia exported almost seven times as much highly-enriched uranium to China for the CFR-600 as all the material removed worldwide under US and IAEA auspices in the last three decades.

China paid about $384 million in three installments for 25,000 kilograms of CFR-600 fuel from Rosatom in that period, according to the RUSI data, which is sourced from a third-party commercial provider and based on Russian customs records.

Rosatom declined to comment. The project “will become the first nuclear power plant with a high-capacity fast reactor outside of Russia,” Rosatom’s TVEL Fuel Company said in a Dec. 28 statement confirming delivery of fuel.

Highly-enriched uranium, defined as the presence of uranium-235 isotopes refined to greater than 20% purity, is a strictly-controlled metal that only a few countries manufacture or possess. The higher the level of enrichment, the closer the suitability for use in weapons, and eliminating the international trade in highly-enriched uranium has been a central pillar of non-proliferation policy since the 1990s.

Read More: How Russia’s Grip on Nuclear-Trade Is Getting Stronger

The CFR-600 is part of China’s ambitious $440 billion program to overtake the US as the world’s top nuclear-energy provider by the middle of next decade. Unlike traditional light-water reactors it runs on a combination of highly-enriched uranium and so-called mixed-oxide fuel that yields weapons-usable plutonium as a byproduct.

China is also building a desert factory in Gansu province designed to extract plutonium from the CFR-600’s spent fuel, once construction is finished in two years. Beijing ceased voluntarily reporting plutonium stockpiles to the IAEA since 2017.

“The increasing secrecy and strong diplomatic efforts against providing greater transparency have raised international suspicion,” said Tong Zhao, a visiting research scholar at Princeton University’s Science and Global Security Program. “I don’t think anyone can rule out the potential military use.”

December’s high-level diplomatic meeting between senior US and Chinese officials in Langfang, a city neighboring China’s capital, was intended to pave the way for US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s first official visit as part of efforts to ease tensions between the world’s two biggest economies.

But tensions spiked again after Blinken’s trip was canceled in February in response to the alleged Chinese surveillance balloon over US airspace that Biden ordered shot down by a warplane. At a security conference in Munich, China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, blasted the US reaction as “hysterical” while Blinken warned Beijing not to supply lethal weapons to Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The danger now is that tit-for-tat recriminations between Beijing and Washington take a nuclear turn once the CFR-600 starts operating, enabling the potential production of plutonium for weapons in years ahead.

“Previously, China had limited itself to what it called ‘minimum nuclear deterrence.’ This potential was much inferior to the American one,” a Russian arms-control expert, Alexei Arbatov, said in a Feb. 6 commentary for the Kremlin-founded Russian International Affairs Council. “But then, apparently, the Chinese decided to match the United States (and, by default, Russia) in terms of the number and quality of nuclear forces.”

Russia has grown increasingly dependent on China since Putin’s year-old invasion of Ukraine prompted unprecedented international sanctions. China has shown it has little intention of abandoning its staunch diplomatic partner against their common US adversary, even as Beijing portrays itself as a neutral actor over the war.

As part of the five-member club of official nuclear-weapons states codified under the 1970 Non-Proliferation Treaty, China and Russia don’t have to report details that might help verify whether the CFR-600 is being used to boost Beijing’s weapons stockpile. The site isn’t subject to mandatory IAEA monitoring, requiring the Pentagon and arms-control analysts to make assumptions about its purpose.

Frank von Hippel, a physicist and former White House adviser now at Princeton University, figures the CFR-600 could produce as many as 50 warheads a year once it’s up and running. “I would expect the enrichment in the HEU for the CFR-600 to be less than 30% - still weapon usable,” even if lower on the spectrum of highly-enriched material, he wrote in an emailed reply to questions.

“For China, getting the technology and fuel is important,” because there aren’t many places where it can obtain plutonium and Russia won’t object if the heavy-metal is used for nuclear weapons, said Alexander Gabuev, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “Whatever is bad for the US and whenever you can strengthen American competitors, is viewed now as a good thing for Russia.”

--With assistance from Rebecca Choong Wilkins and Lucille Liu.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.