Jan 17, 2022

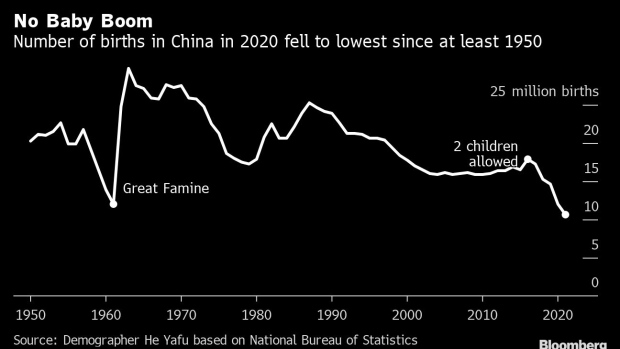

China’s Population Flatlines With Fewest Births Since 1950

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China’s population crisis continued to worsen in 2021, with the latest birth figures again sliding despite government efforts to encourage families to have more children.

There were 10.62 million babies born in China last year, down from 12 million in 2020, according to data released by the National Statistics Bureau on Monday. That’s the fewest number of births since at least 1950, according to calculations based on official data. The birth rate, or the number of newborns per 1,000 people, dropped to 7.52 last year, the lowest level since at least 1978.

The precipitous fall in the number of new babies means the population of the world’s largest nation will likely start falling even earlier than expected. There were some forecasts that it could shrink this year, but the 10.1 million deaths was slightly lower than births, postponing that milestone for a while longer.

The drop in the number of women at optimal age for childbearing, changing attitudes toward raising children and the impact of Covid-19 all contributed to the decrease in births, Ning Jizhe, head of the National Statistics Bureau, said at a press briefing in Beijing on Monday. However, the population will continue to hover at around 1.4 billion people, with around 10 million newborns expected in years to come, he said, as the new three-child policy gradually takes effect.

There were 1.41 billion Chinese people in mainland China at the end of last year, a 480,000 increase from the level at the end of 2020. Of those, 62.5% were of working-age, which China defines as people aged 16 to 59, down from more than 70% a decade ago, highlighting the challenges the country faces as its population ages.

The count excludes foreign citizens in China and the populations of Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Last week, a controversial economist was banned from China’s Twitter-like Weibo platform after he called for the central bank to print 2 trillion yuan ($314 billion) a year for a decade to help boost the fertility rate. Ren Zeping, China Evergrande Group’s former chief economist, went on to argue in an article that women born between 1975 and 1985 should be the focus group for childbearing, as those born from the 1990s are not even willing to get married.

Although such remarks were widely criticized as sensationalist, Ren’s comments might have shed some light on the challenges facing the authorities. Decades of stringent birth controls, a feminist awakening and uncertainties of the lingering Covid-19 pandemic have changed younger generations’ attitudes toward family life.

Beijing has struggled to arrest the country’s declining birthrate for years. While easing the stringent one-child policy in 2013 and allowing each family to have two children in 2016 led to a small up-tick in births, the effect was temporary. After births in 2020 dropped to the lowest level since 1961, Chinese authorities effectively got rid of any restrictions on the number of children families can have.

There are now various efforts to make it easier to have more children, including making education cheaper by wiping out the for-profit after-school tutoring industry, issuing a new guideline to reduce abortions, and even beginning to overhaul a decades-old law to better protect women’s rights.

Regional governments across the country have also taken action. By late November, at least 20 provinces had come up with their own measures to boost fertility, according to the official Xinhua News Agency, from extending maternity and paternal leave to offering subsidies and providing baby loans.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.