Jan 10, 2023

China’s Population Likely Shrank in 2022 as Births Hit New Low

, Bloomberg News

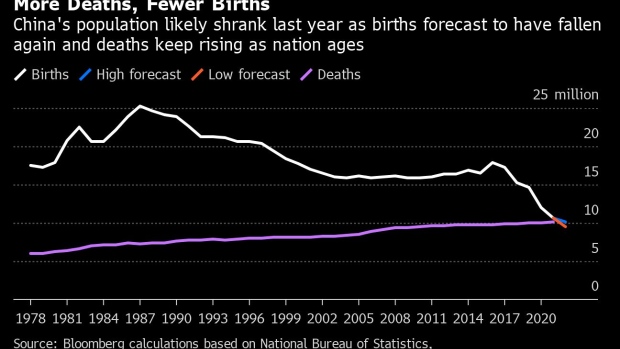

(Bloomberg) -- China’s population likely started shrinking last year for the first time in decades, experts say, a significant milestone that will have long-term repercussions for the economy.

The government’s official data for total number of births in 2022 — expected to be released next week — will probably show a record low of 10 million, according to independent demographer He Yafu.

That would be less than the 10.6 million babies born in 2021, which was already the sixth straight year of declines and the lowest since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. He added that the country likely recorded more deaths last year than the 10.1 million people who died in 2021, in part because of the spread of Covid infections.

The anticipated population drop-off is coming much faster than previously expected, and could curb growth in the world’s second-largest economy. The labor force is already shrinking, long-term demand for houses will fall further, and the government may also struggle to pay for its underfunded national pension system.

The upshot is that China’s economy may struggle to overtake the US in size and it could lose its status as the world’s most populous country to India this year.

Births fell in many nations during the pandemic as people feared going to hospitals, lacked family support because of lockdown restrictions and balked at child-care costs.

China, however, faces additional problems spurred in part by the decades-long enforcement of a “one-child policy” that skewed the gender ratio, given the traditional preference among Chinese parents for sons. That has led to a decline in the number of women of child-bearing age that will be hard to reverse — even after the government ended the policy and allowed families to have more children.

Some regions have started offering incentives for couples to have kids. Shenzhen, which neighbors Hong Kong, is working on plans to subsidize parents until their children turn three. Financial aid could be as high as a one-off payment of 10,000 yuan, along with an additional 3,000 per year.

Healthcare authorities in Shenzhen have acknowledged the challenges, saying in a statement accompanying those incentive proposals this week that the city’s population situation was “by no means optimistic.” New births have fallen for four straight years, they said, adding that the number of women of child-bearing age has fallen 8.7% since 2015.

“The measures taken to boost birth rates have been far too little and too late, and were completely overwhelmed by the impact of Covid Zero on birth rates,” said Christopher Beddor, deputy China research director at Gavekal Dragonomics.

“The core issue is that there’s only so much policy can accomplish in this realm, because declining birth rates are driven by deep structural factors,” Beddor said, adding that economic challenges posed by China’s aging and shrinking population have been discussed for years. “The leadership seems to have belatedly realized that those issues are very real and arriving very quickly.”

As recently as 2019, the United Nations was forecasting that China’s population would peak in 2031 and then decline. By last year, though, the UN had revised that estimate to see a peak at the start of 2022. It now expects China to lose 110 million people by 2050 and fall to about half its current size by the end of the century.

The fall in the working-age population will be even greater: That group will slump to about 650 million people in 2050, a drop of about 260 million from 2020, according to Bloomberg Economics.

They forecast that the demographic headwinds will cut into the long-term growth potential of the economy unless government policies to promote having children start to be effective.

It may take a few years for the population to settle into a steady contraction, according to Yuan Xin, a demographics professor at Nankai University in Tianjin. He cited the government’s decision to ease birth limits and introduce policies to encourage childbirth.

“Usually population growth would hover around zero for a few years before one can conclude that a country has entered the phase of population contraction,” he added.

The economy also may not feel an immediate hit from the population decline. Labor can still be shifted from less-productive or rural sectors, such as farming, to other areas, according to Wang Tao, head of Asia economics and chief China economist at UBS AG. “Total labor supply for the non-farming sector can still go up,” she said.

A change to the retirement age may address some of the issues, she added. Countries such as Japan have been successful in maintaining the total size of the labor force even as the population aged and shrank, as more older people worked and women who’d left the workforce to raise a family returned.

China would have to overcome some challenges, though. The topic has been discussed for years but never implemented at scale, and has frequently sparked public outcry. The country has kept that age — 60 for men and 55 for women white-collar workers — unchanged for more than four decades, even as life-expectancy has risen. By contrast, most men and women in Japan and Taiwan can retire and start drawing a pension a few years later.

The issue may come up again soon. At last month’s Central Economic Work Conference, China’s leadership said that they would “push forward the postponement of legal retirement ages in a gradual manner at the right time to actively deal with the issues of population aging and low birth rate,” according to a readout of the meeting.

--With assistance from Jing Li, Fran Wang and Phila Siu.

(Updates with Shenzhen’s birth incentive plan in the eighth and ninth paragraphs.)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.