Feb 6, 2023

China’s Rapid Covid Reopening Tests PBOC’s Easing Path

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The calculus behind the People’s Bank of China’s pledge to use monetary policy to bolster the economy has been altered by the faster-than-expected recovery following the scrapping of Covid restrictions.

The rapid rebound in consumption and services following the sudden ditching of Covid Zero in December has left some economists questioning the need for more stimulus. However, sectors including property, durable goods, manufacturing and exports remain weak, meaning the PBOC may still see a need to follow through on its vow last month to stabilize growth and support domestic demand, with some still expecting a cut to either the required reserve ratio or interest rates.

The other variable is inflation. While still well below the 3% target for the full year, the consumer price index is set to climb to 2.2% in January from December’s 1.8%, data on Friday is forecast to show.

“The reopening momentum of in-person activities is reasonably good, which means less need for the PBOC to cut interest rates or RRR in the near term,” said Zhong Zhengsheng, chief economist at Ping An Securities Co. who consulted with Premier Li Keqiang in 2020. He sees a window for a rate reduction in the second quarter if a second wave of Covid infections hit.

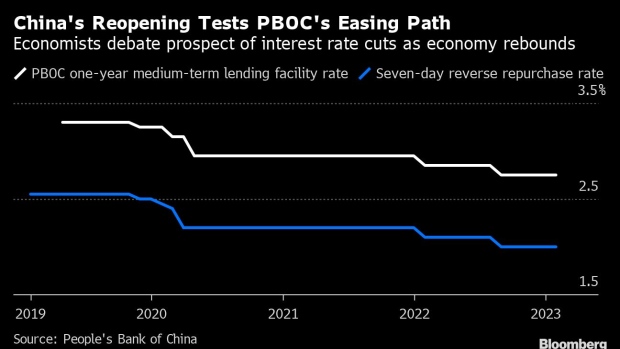

The PBOC kept its monetary easing measured in 2022 and relied more on structural tools to provide targeted support to the economy, even as Covid outbreaks and lockdowns dragged growth to the second-lowest level since the 1970s. Authorities were wary of overstimulating the economy and wasting policy space, and there was concern that easing faster when the Federal Reserve and other global central banks were tightening would put even more pressure on the yuan to depreciate.

However, the gap between the PBOC and its foreign peers might start to shrink this year, with investors now forecasting the Fed will start to cut rates by the end of the year. That lower external pressure meant the yuan has strengthened since November on expectations for the Fed to slow its tightening and the better economy in China.

The yield gap between US and China’s 10-year sovereign bonds has narrowed to around 60 basis points from a peak of around 150 basis points in early November. That means the value of buying Treasury bonds compared with Chinese ones is shrinking, alleviating capital outflow pressures, attracting overseas investors, and also giving China’s central bank greater space to cut rates now should it wish to do so.

Some economists expect the PBOC to trim the RRR to replenish interbank liquidity this year. Zhong of Ping An predicts a total of 50 to 100 basis points of cuts in 2023, with potential windows at mid-year, when liquidity is usually tight, and in the fourth quarter, when a large amount of policy loans will mature.

Others, like Standard Chartered Plc’s Ding Shuang and Bloomberg Economics’ David Qu, predict a cut in the one-year policy rate in the first quarter. “Monetary policy still has an important role to play” before the government budget is approved in March and the effect of fiscal policy starts to kick in, said Ding, chief economist for China and North Asia at Standard Chartered.

Structural tools will likely play an even more significant role in 2023 after authorities expanded special programs in the past few years, as Beijing aims to funnel funds into targeted areas such as infrastructure, the completion of housing projects and green sectors. Any drop in deposit rates could also lead to a decline in banks’ benchmark loan prime rate even without a policy rate cut.

If inflation were to speed up it might limit the central bank’s options, although in the past few years it has cut interest rates or the RRR despite structural and supply-driven price pressures such as high factory-prices and high pork prices. Consumer inflation has stayed below the 3% target over the past decade, a contrast with soaring consumer prices in advanced economies recently, and there are reasons to be optimistic that inflation will remain mild.

Disruptions to supply chains and logistics from Covid lockdowns will be much smaller than in 2022, while more workers are likely to return to the job market. The risk of absenteeism is low as the government has avoided handing out cash subsidies to individuals and social welfare is insufficient, while the jobless rate remains elevated, meaning that competition for jobs and thus pressure on wages may not be as fierce as elsewhere.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.