May 19, 2022

China’s Stimulus Tops $5 Trillion as Covid Zero Batters Economy

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China’s plans to bolster growth as Covid outbreaks and lockdowns crush activity will see a whopping $5.3 trillion pumped into its economy this year.

The figure -- based on Bloomberg’s calculation of monetary and fiscal measures announced so far -- equates to roughly a third of China’s $17 trillion economy, but is actually smaller than the stimulus in 2020 when the pandemic first hit. That suggests even more could be spent if the economy fails to pick up from its current funk -- a possibility raised by Premier Li Keqiang earlier this week.

“The mainstay of policy this year is fiscal spending and government investment, while the central bank is only playing a supportive role so far,” said David Qu, China economist at Bloomberg Economics. “There’s still a lot of space for a stronger fiscal policy, which is more effective in supporting growth now.”

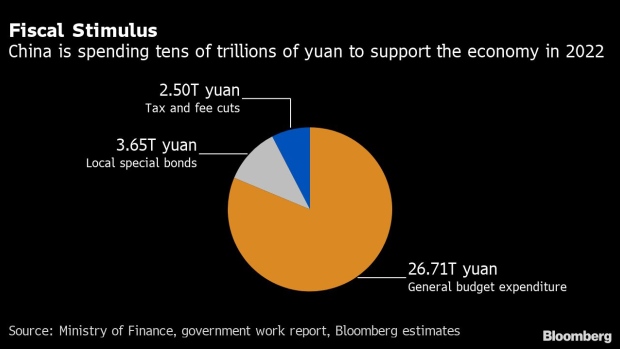

Bloomberg’s calculation of financial support pledged so far for 2022 amounts to 35.5 trillion yuan. On the fiscal side, we’ve added China’s general budget expenditure with the amount of money issued through local government special bonds and tax and fee cuts. Monetary policy support includes hundreds of billions of yuan in liquidity unleashed by the People’s Bank of China through policy loans, cuts to reserve ratios for banks, as well as cheap loans to help small businesses and green projects during the pandemic.

The world’s second-largest economy has come under immense pressure to meet the government’s growth target of about 5.5% for the year. As Shanghai and other cities and regions locked down this spring to contain Covid outbreaks, industrial output and consumer spending sunk to the lowest levels since early 2020.

Read More: China’s Stimulus Isn’t Going to Save Global Economy Like in 2008

While authorities have promised to reach their economic goal, top leaders have also made it clear they’re sticking with Covid Zero, prompting skepticism among economists about whether Beijing can achieve both objectives at the same time.

The fact that most of the stimulus was announced at the annual session of the National People’s Congress in early March, well before most of the lockdowns, suggests that authorities may announce more measures as needed this year. However, the central bank is likely to move cautiously, wary of diverging too much from hawkish policies elsewhere to combat runaway inflation, or repeating a strategy akin to its response to the 2008 financial crisis, which led to soaring debt.

“China may need additional support if the economy continues to slump rapidly,” said Ding Shuang, chief economist at Standard Chartered Group Plc. Credit growth will likely pick up, he said, as the PBOC recently said the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio would rise this year. He also expected infrastructure financing to climb, property loans to normalize, and targeted lending to sectors such as small businesses and green projects to also rise.

Whatever China puts up in support this year, it’s still dwarfed by the massive stimulus plan that helped the economy return to its high-growth trajectory after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. The 4 trillion yuan in additional investment announced that year alone accounted for 13% of the economy. The PBOC was also more aggressive during that period, cutting its benchmark lending rate by more than 200 basis points in a single year and bringing down the reserve requirement ratio by as many points.

“There are more challenges to shore up growth now than it was in 2008,” Qu said, adding that interest rate levels at that time were high, allowing the PBOC to unleash greater stimulus. Investing was also more attractive, as the economy was growing at a faster pace. The rest of the world was ramping up stimulus to shore up the global economy, too.

Now, he said, “China is facing all these problems alone.” Government-led investment is the “only thing that can be hoped for in the short term,” he said.

Here’s a look at Beijing’s fiscal and monetary support this year:

PBOC Measures

The PBOC hasn’t eased much this year, having only cut its policy interest rates once in January by 10 basis points. That compares to two cuts totaling 30 basis points in the first four months of 2020.

The central bank also reduced the reserve requirement ratio -- the amount of money banks have to hold in reserve -- a single time, less than the three cuts made by this point in 2020. The change to the ratio in April, the first reduction since last December, unleashed about 530 billion yuan of long-term liquidity into the economy.

The central bank has other tools in its arsenal aside from adjusting policy loans and reserve ratios. It’s increasingly been making use of its relending program, which provides cheap loans to commercial banks for targeted lending to small businesses and other areas designated as in need of relief.

The PBOC also announced plans to transfer 1.1 trillion yuan to the central government this year, resuming a practice that had been suspended during the pandemic. That transfer replenishes the central government’s fiscal resources outside of the general budget, while also increasing the amount of base money in the economy.

As much as 800 billion yuan has been transferred so far this year -- a move equivalent to an RRR cut of 0.4 percentage points.

Fiscal Measures

The bulk of the government support this year comes in the form of fiscal stimulus, including a general budget expenditure target of 26.7 trillion yuan -- nearly 2 trillion yuan more than that of 2021.

The rest of the money will come from tax cuts and rebates, along with a 3.65 trillion yuan quota for local government special bonds, a key source of funding for public projects such as infrastructure.

There is also 2 trillion yuan available from above-budget income, as well as funds left over from below-budget spending in the government fund account in 2021 that authorities can use on infrastructure and other public projects if needed, according to Qu.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.