Mar 6, 2021

China’s Top Leaders Leave Tough Climate Decisions to Bureaucrats

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

Slowing global warming comes down to cutting emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases. There are different ways to get there, but a country's policies flow from that top-level target. China, the world’s biggest polluter, fell short when it unveiled its goal for the next five years.

The world’s second-biggest economy said Friday it plans to lower emissions per unit of gross domestic product by 18% by 2025—the same level it targeted in the previous five-plan. The lack of new ambition was conspicuous after President Xi Jinping won international praise in September for pledging to get China to net zero by 2060.

The new targets were in line with where current trends show China is heading anyway. Plans to get a fifth of the country’s energy from non-fossil fuel sources by 2025 would mean growing its wind and solar generation by an average of 12% a year, about the same rate U.S. installations increased under former President Donald Trump, who actively opposed green energy.

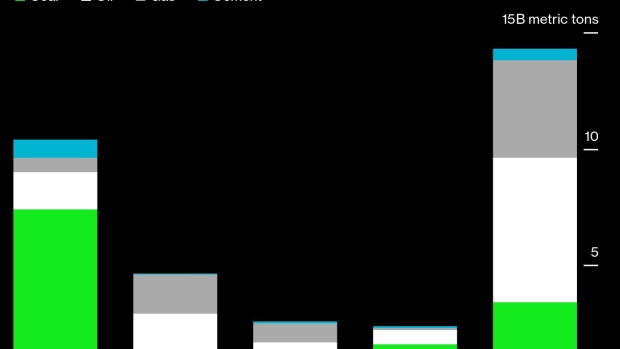

The policies may get China to peak emissions by 2030, which is its pledge under the Paris Agreement. But that isn’t enough to help the rest of the world slow global warming in time, according to research by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. The group estimates that China would have to cap carbon dioxide emissions around 9.3 billion metric tons by 2030 to reach net zero in 40 years. Rhodium Group estimates that China’s energy sector generated 10.2 billion tons of CO₂ last year.

China has so far resisted setting an absolute limit on emissions, choosing instead to set targets as a share of growth. After all, it’s still growing at multiple times the rate of developed countries such as the U.S., and emissions will probably continue to rise considerably. China was the only major economy to grow in 2020 after quickly containing the coronavirus outbreak, and accounts for about 30% of global emissions.

Climate experts more broadly agree that China will have to reach peak emissions around 2025 if the world has a chance of achieving the Paris Agreement’s aspiration of limiting the average global temperature rise to 1.5ºC from pre-industrial levels. “Everything else risks leaving the heavy lifting to the period after 2030,” said Myllyvirta.

China’s top officials largely delegated the difficult decisions to the different ministries and state-owned enterprises that oversee the country’s energy sector. In the coming months, the energy administration will provide specific targets for wind, solar, hydro, oil and coal power use over the next five years. Provincial governments will have to say what they’re going to do. China will also release a five-year climate plan for the first time, led by the environment ministry.

China hasn’t released an official roadmap for carbon neutrality, but Friday’s five-year plan is consistent with the two-speed approach proposed by climate researchers at Tsinghua University. They suggested keeping emissions reduction small before 2035, leaving most of the hard work to the second half, when researchers argued cutting emissions — and by proxy slowing growth — will have less of an impact on a wealthier society. They also assume that China will by then be able to rely heavily on new clean energy sources such as hydrogen as technological breakthroughs will have made them cheap enough.

Choosing that route will allow the country’s powerful fossil fuel industries to build more capacity and further entrench their place in the nation’s economy. China mines and burns half the world’s coal, and any serious effort to tackle climate change will have to shrink the industry significantly. The five-year plan doesn’t lay out hard targets for cutting coal use, and instead says China will continue domestic production of fossil fuels like coal and oil.

The document as a whole illustrates China’s struggle going forward. On one hand, Xi wants to build what he calls an “eco-civilization,” and support for environmental protection is growing among the public. On the other, local governments are already finding ways around Xi’s green agenda and the fossil fuel industry continues lobbying hard for its expansion — for example, seizing on a power shortage this winter to argue for more energy security.

A lot hinges on how much the environment ministry can persuade other ministries and state-owned companies to take China’s 2060 goal seriously. Since taking on the task of reducing emissions in 2018, it has been relatively toothless, though it appears to have gained sway after Xi’s net-zero pledge. The five-year plan sets a target of “basically eliminating” heavy air pollution by 2025, boosting forest coverage to 24%, cleaning up the nation’s rivers, and restoring wetlands. How far China goes in implementing these policies will be a sign of how effective the ministry is becoming.

Earlier this year, an “environmental inspection team” from the ministry publicly criticized the powerful National Energy Administration for failing to rein in coal power generation. The language was unusually tough, and showed the top leadership could potentially side more with environmental policies in the next five years, said Dimitri de Boer, chief China representative of nonprofit ClientEarth.

There’s also a chance that China could be waiting for global climate talks in November to upgrade its goals. Xi has sought to position himself as a leader on the issue, and China is set to host an important United Nations biodiversity conference this year. It’s also in the midst of rebuilding ties with the U.S. under President Joe Biden, with climate essentially the only area for possible cooperation after disputes over everything from human rights to trade and the coronavirus.

During the first phone call between the two presidents, both countries mentioned climate as an area of shared interest. China hasn’t officially submitted its updated Paris commitments for the upcoming COP26 gathering. It’s important to watch if it further strengthens its targets after the U.S. announces its new goals in April, said Li Shuo, a climate policy advisor at Greenpeace East Asia.

“China needs to bring its emission growth to a much slower level, and to flatten the emission curve early in the upcoming five-year period,” he said. Still, the nation has traditionally set itself targets that are easily met. “The habit of the Chinese government to under-promise and over-deliver will hopefully preserve space for more ambition,” Li said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.