Jun 23, 2020

China Threatens U.S. Space Power By Completing Satellite Network

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- A Long March-3B rocket took off from a launchpad in Sichuan province Tuesday to put a satellite in orbit, giving China a win in its intensifying rivalry with the U.S. and boosting its ability to be self-reliant in new technologies.

The five-ton satellite is the final piece of the Beidou network, a collection of several dozen satellites that is China’s alternative to the U.S.-run Global Positioning System. GPS provides navigation and timing data that is essential to operating everything from massive container ships to electric cars while also tracking the microchip in your dog.

Completion of the Beidou network, estimated to cost more than $10 billion, is the latest milestone in China’s decades-long effort to become a power in space. In May, state media trumpeted the test flight of a next-generation spacecraft designed to take Chinese astronauts to the moon. China plans to send a robotic mission to explore Mars this summer and is moving ahead with plans to build its own space station.

“This year is the time when China’s long-term space ambitions meet their fruition,” said Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. “In some ways, they stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the U.S. as a major space power.”

These ambitions haven’t gone unnoticed in Washington, with the U.S. locked in an intensifying fight for global dominance with Beijing. NASA is determined to stay ahead. The agency has a Mars robotic probe scheduled for launch this summer and wants to send a crewed mission back to the moon by 2024. NASA in April picked Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin LLC and Elon Musk's Space Exploration Technologies Corp. to develop lunar landers. SpaceX launched two astronauts into space last month, the first travel by Americans aboard a U.S. spacecraft since the termination of the space shuttle program in 2011.

The situation mirrors the Cold War rivalry between the Americans and the Soviets, said Nilton Renno, professor in the department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering at the University of Michigan. “They will be stronger competition for the U.S., not only in the space program but also in world dominance,” he said. “I’m sure the U.S. will be more careful about messing with the Chinese. They are getting stronger and more independent.”

Beidou (the Chinese name for the Big Dipper) dates to the 1990s, though its first-generation satellites couldn’t compete with GPS. China began developing the most recent version in 2009, using more advanced satellites to expand its reach globally. According to state media, Beidou now has more capacity for two-way messaging than GPS and is more accurate. Beidou “will bring new highlights to global navigation satellite systems,’’ Ran Chengqi, director of the China Satellite Navigation Office, told state media, referring to positioning and messaging.

The system already is used by companies doing business in China. Huawei Technologies Co. makes mobile devices that connect to Beidou, and about 7 million vehicles adopted the system by the end of last year.

But the network could have more contentious applications. Beidou also could help the People's Liberation Army develop systems relying on satellite communication that would face fewer risks of being disabled by the U.S. Air Force, which operates GPS, said Larry Wortzel, a member of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

A completed Beidou network also should help President Xi Jinping progress toward his goal of upgrading the Chinese economy by 2025 to make it less reliant on foreign technology. Local companies will have an edge when it comes to supplying Beidou-enabling semiconductors and other equipment, said Dean Cheng, senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Center.

“The Chinese would like to have everyone buy a Beidou receiver and for companies to use Beidou for their trucks, fleet, aircraft and ships,” Cheng said.

At a time when millions of people are sick and economies are crumbling because of Covid-19, China’s space program may help divert attention from the country’s role in the health crisis, said Steve Eisenhart, senior vice president at the Space Foundation, a nonprofit organization in Colorado Springs, Colorado. “There is a strong desire on the part of the Chinese to be more open about their space program to draw attention to things other than the pandemic and all the criticism associated with it,” Eisenhart said.

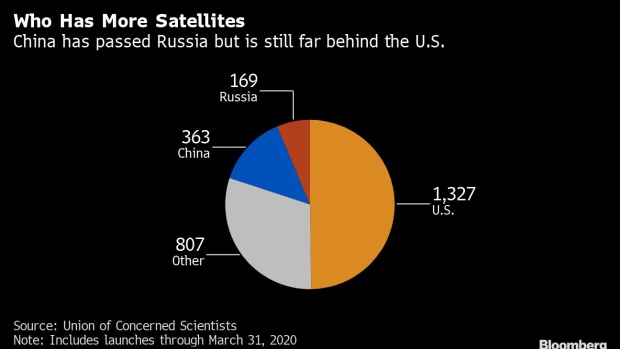

China still cannot match the U.S. in many space projects. The first Chinese astronaut isn’t likely to set foot on the moon until sometime in the 2030s, more than six decades after Neil Armstrong took the first step there. China’s Mars mission will deploy the country’s first rover for the planet, something NASA did in 1997.

“The relative gap between the accomplishments of the U.S. space program and the Chinese space program has narrowed, but the U.S. is still the leader,” said Brian Weeden, director of program planning at the Secure World Foundation, a space-focused think tank in Washington.

The pressure to catch up may have contributed to a major incident last month, when part of a Chinese rocket crashed in the West African nation of Cote d'Ivoire. Chinese authorities seem to have lost control of the craft by the time it fell to Earth, according to the U.S. Space Command. The crash earned China a public rebuke from NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine.

China hasn't admitted that a problem occurred, and Chinese media has been largely silent. Weibo, a leading social media platform in the country, labeled accounts of a crash as “false information.”

When asked about the incident, a Foreign Ministry spokesman said he had no information.

An uncontrolled re-entry raises the possibility that China, as it races to catch up with the U.S. in space, may be cutting corners to save money and time, said Weeden, who added Chinese technicians should have been able to guide the rocket out of orbit safely.

Still, the incident shouldn’t detract from the significance of Beidou’s completion, he said. “They’ve proven that they’re an independent space power,’’ Weeden said. “And they can do a lot of things that the U.S. can do.”—With Bruce Einhorn, Jing Li and LeAnne De Bassompierre

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.