Aug 18, 2022

China Vows to Ensure Unmarried Mothers Get Equal Maternity Leave

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China has vowed to ensure unmarried mothers receive maternity benefits, as the world’s second-largest economy revamps a slew of policies in a bid to boost its falling birthrate.

Liu Juan, deputy director of payment security at the National Healthcare Security Administration, said Wednesday that marriage licenses shouldn’t be required to claim maternity benefits, responding to reports some regions were demanding such documents.

“The issue you are concerned about is one we are also aware of,” she told reporters at a news briefing in Beijing. “We’ll work with the relevant departments to ensure we can better protect the legitimate rights of the insured.”

China’s National Health Commission on Tuesday rolled out a policy framework with new guidelines on tax, housing, employment and education policies designed to ease the financial burden of having a child. Seventeen ministries collaborated on the document, which the Communist Party’s Global Times newspaper called a “rare” coordination “underscoring the seriousness” of the population problem.

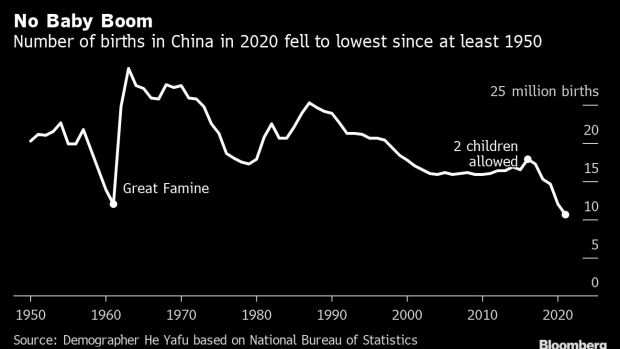

READ: China’s Population Flatlines With Fewest Births Since 1950

The drive to ensure unmarried women can collect maternity benefits was the second-highest trending topic on China’s Twitter-like Weibo on Thursday morning, sparking discussion of the country’s notorious family planning policies that previously limited families to a single child.

Many applauded the move as an advancement, after Chinese authorities for decades penalized mothers outside wedlock by excluding them from certain health care benefits in a bid to push what some see as traditional family values.

“Finally we have some progress,” one user wrote. “This was really so hard earned.” Another said: “This is the first step in liberating women’s maternity rights.”

China is facing a population crisis. The Asian giant reported its fewest births since 1950 last year, with 1.4 million fewer babies born in 2021 compared to 2020. Beijing is struggling to arrest that decline after decades of stringent birth controls. A feminist awakening and now uncertainties of Covid curbs have changed younger generations’ attitudes toward family life.

After relaxations to the one-child policy in 2013 and then 2016 led to only a small up-tick in births, the government further relaxed its policy in 2021 to allow women to have up to three children. But economists have warned measures to alleviate housing and education costs were needed to significantly change the trend.

Since then, Beijing has made reforms to encourage couples to have more children. In December, the country proposed a bill to ban employers from asking women about their marital and pregnancy status, as part of an overhaul of its nearly three-decades-old women’s rights law.

The Communist Party has been less receptive to broader calls to improve women’s rights, however, repeatedly suppressing the nation’s nascent #MeToo movement, which it views it as a vehicle for spreading liberal Western values.

READ: Attack on Chinese Women Revives #MeToo Anger Xi Can’t Extinguish

The policy framework rolled out this week called for broader institutional support for families, including improvements to prenatal care and children’s health and education, as well as tax deductions, preferential housing loans, and insurance benefits to those with children.

Still, many on Chinese social media said the guidelines didn’t go far enough for a generation without siblings bearing sole responsibility for elderly relatives, who now make up nearly one-fifth of the population. Adding to the problems are an economic slowdown, record youth unemployment and a housing crisis.

“Those of us who are only children born in the 1980s have to take on all of the burden,” one unidentified user in Guangdong wrote. “We don’t have a house or a car, and we certainly can’t afford a child.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.