Mar 1, 2021

Chocolate makers have sweet-loving Indians in their sights

, Bloomberg News

India has long been known for its love affair with sugar. Sweets play a major role in festivals and family celebrations and delicacies such as gulab jamun -- fried dough balls soaked in syrup -- and barfi -- made with condensed milk -- are popular gifts. Not only is the country the world’s biggest consumer of sugar, it’s also one of the top producers.

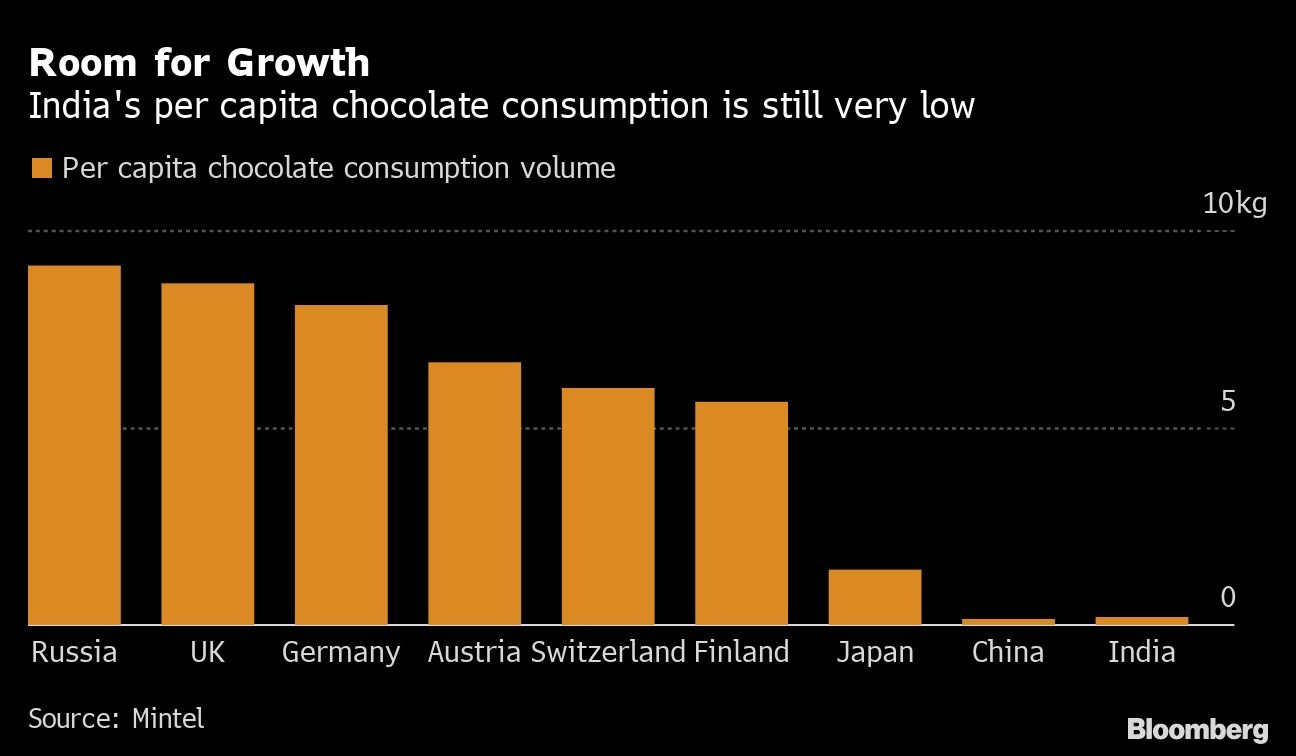

That penchant for sweet confections together with a massive, youthful and increasingly affluent population has chocolate-makers around the world sitting up and taking notice. Indians currently eat only about a 10th as much chocolate confectionery as the global average and the International Cocoa Organization recently described the country as the No. 1 potential market of the future.

Chocolate -- as well as ice cream, cakes and milk shakes -- is already starting to displace traditional treats among the middle classes. No longer just something to be given at special occasions such as weddings or the Diwali festival, it’s becoming an everyday snack for many Indians. The country’s chocolate market was estimated to be worth 172 billion rupees (US$2.3 billion) in 2019 and will grow by 6.7 per cent a year from 2020 to 2024, according to Mintel.

The rise of India as a chocolate consumer comes at a welcome time for a global industry struggling with stagnating sales as people seek out healthier snacks. Virus lockdowns are also posing a challenge in the shorter term, with cocoa prices in New York posting their biggest quarterly drop in a year.

As the global outlook dimmed, Barry Callebaut was building its presence in India. From just a single employee in 2007, the chocolate titan now has 200 staff and has just opened its third factory.

The changing face of India’s retail landscape is one of the key drivers of consumption, according to the Swiss company. While small neighborhood stores and traditional grocers remain the most popular places to buy chocolate, particularly in lower-tier cities and rural areas, the rise of supermarkets and modern retail in places like Mumbai is boosting the availability of chocolate, said Dhruva Sanyal, Barry Callebaut’s managing director in India.

“More consumers are choosing to shop at modern retail stores such as hypermarkets and supermarkets on a weekly or monthly basis,” he said. “This is encouraging modern retailers to expand their product range, and food such as chocolate is now prominently available.”

E-commerce and the internet are also boosting sales as Instagram-savvy manufacturers harness the power of social media to appeal to millennials. “What many pastry chefs and foodies have done with their social media is providing tremendous access to the chocolate culture in India,” Sanyal said.

There’s also a growing interest in premium products such as Les Recettes de l’Atelier, Nestle SA’s luxurious collection of chocolate tablets, and ITC Ltd.’s Fabelle Trinity range. High-quality chocolates are expected to grow to 80 per cent of the total market in a decade from 20 per cent now, the International Cocoa Organization said. This would represent a complete flip of the current split with the lower-quality category of chocolate that’s produced from vegetable oil.

A growing health-consciousness and the fact that India has a rising number of vegans is also shaping the evolution of the industry in the country. Another key challenge for chocolate makers will be how to overcome the price-sensitive nature of the market and the plethora of cheap alternatives. They’ll also be hoping there won’t be any more scandals like the one in 2003 when customers found worms in Mondelez International Inc.’s Cadbury Dairy Milk bars.

Swagatika Priyadarsani, a sales manager at an insurance company, said she prefers darker chocolate because of the taste and the lower sugar content. The 20-something, who lives in the city of Bhubaneswar in the eastern state of Odisha, said she felt better about giving dark chocolate rather than sugary local treats to younger relatives and the children of friends.

Amul, the country’s biggest dairy company, is tapping into this preference and is offering more bitter varieties with a higher cocoa content. The company is currently doubling its chocolate production capacity.

“One expects cocoa consumption to increase but not the sugar addition in that,” said R.S. Sodhi, managing director of the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation Ltd., which owns the Amul brand. “Our dark chocolate business has been growing at more than 100 per cent in the last two years.”

Niche varieties of chocolate could also prove popular in India due to the high numbers of vegetarian, vegan and lactose-intolerant people.

Gurgaon-based startup Piperleaf India Pvt. is marketing “mylk chocolates” with a rich cocoa and creamy hazelnut paste as an alternative to dairy. It’s also planning to introduce sugar-free bars and chocolate gift boxes by August to coincide with Raksha Bandhan, a Hindu festival celebrating the bond between siblings at which gifting sweets is an essential part of the occasion.

“We are witnessing a shift in consumer preferences in India, with people increasingly getting attracted toward vegan products and becoming health conscious,” said Anshul Agarwal, Piperleaf’s founder. “The Indian chocolate market is bound to grow at a fast pace as per-capita consumption is still very low, incomes are rising and people are looking for quality alternatives.”