Jul 12, 2016

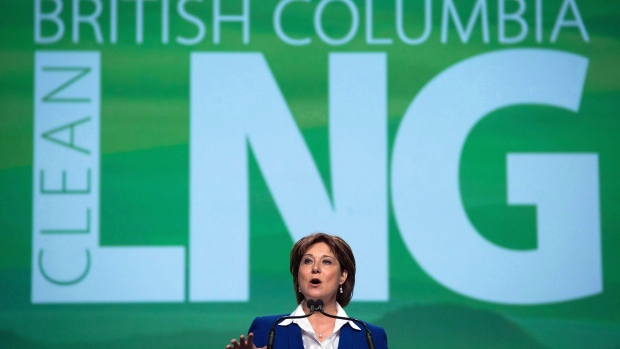

Christy Clark's jab at Alberta comes back to haunt amid LNG uncertainty

ANALYSIS: “Vigilance” will not save the nascent British Columbia liquefied natural gas export industry.

In the last agenda-setting throne speech from the westernmost Canadian province in February, B.C. warned against the pitfalls of relying too much on natural resources for economic growth. The words were a direct shot at neighbouring Alberta, which still derives more than 25 per cent of its gross domestic product from the energy sector.

“It has never been more important to stay vigilant,” B.C. Lieutenant-Governor Judith Guichon said in the Feb. 9 address. “Over the decades, Alberta lost its focus. They expected their resource boom never to end.”

Yet as hopes for a vibrant west coast LNG export sector being up and running by the end of this decade dwindle, B.C. finds itself in a very similar position to Alberta.

Growth in the oil sands is broadly expected to stop by around 2020 and with it, hopes of creating roughly 100,000 new well-playing jobs in the next decade. B.C. was counting on similar growth from LNG. Premier Christy Clark even made the promise of 100,000 new LNG-related jobs and $100 billion in added government revenue from new LNG-related taxes over three decades the centerpiece of her 2013 reelection campaign.

Now, it seems, that promise will almost certainly be broken.

LNG Canada, a $40-billion proposal backed by Royal Dutch Shell and PetroChina to export LNG from the coastal town of Kitimat, delayed a final investment decision this week on the project for the second time this year. While CEO Andy Calitz stressed in a conference call with reporters on Monday the project was being delayed and not cancelled, he refused to provide a new timeline for when the decision can be expected.

Of more than two dozen projects which have been proposed to export LNG from B.C., only LNG Canada had all the necessary regulatory approvals in hand to move forward. Global economic factors – the spread between Asian and North American natural gas prices has been cut in half over the past two years and there is already enough new LNG export capacity under construction around the world to grow supplies by 58 per cent over five years – were cited as the main reason for the latest delay.

Pacific Northwest LNG, the other leading proposal for a $38-billion export plan centered on a terminal just outside of Prince Rupert, is still waiting for final regulatory approval after multiple delays. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency launched a three-month extension period to its review on July 2nd, meaning Ottawa will have until October to decide whether to sanction the project.

Even if the government gives a green light, Pacific Northwest LNG is still facing resistance from local First Nations communities and the environmental lobby over potential threats to local fish habitats. And even if it manages to overcome those hurdles as well, it is highly probable Pacific Northwest LNG will face the same economic challenges as LNG Canada; particularly when the massive companies backing these projects are prioritizing less expensive so-called “brownfield” projects that do not require entirely new facilities to be built.

Unless there are unexpected and calamitous changes to the global gas business over the next several months, Clark’s hopes of having a major new revenue stream and source of job creation in time for her next reelection pitch in the new year appear highly unlikely.

That may not be an issue right now: B.C. is expected to lead economic growth in this country over the next couple of years largely on the strength of its real estate sector. Housing prices, particularly single-detached properties in and around Vancouver, have been spiking by as much as 40 per cent over the past year; leading a growing chorus of experts to warn of bubble conditions whereby prices could crash.

If that bubble were to pop, the province would quickly find itself without another source for substantial economic growth. And even if it doesn’t, B.C. could still find itself targeted in the next Alberta throne speech as an example of how not to build expectations for an industry based on global economic factors beyond local control.