Jun 28, 2022

Controversial Law Could Remake English Countryside — And Not in a Good Way

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Peter Gantlett was out in the fields when he heard the phone ring. It’s the second strange call his family-run organic farm in southwest England has received recently, pitching the same thing: newt ponds.

Ponds for great crested newts — an endangered species threatened by housing and infrastructure development — have been popping up across the country over the past year as the government rolls out programs to protect them. Environmental service providers, like the ones who have been contacting Peter, broker deals to create new habitats for these creatures on private land.

Currently the core incentive to host ponds is a one-off payment, but that is set to change. A new rule — due to come into force in England next year — will create the country’s first nationwide biodiversity offset market, which could turn such habitats into a regular source of revenue. Soon, Peter and his family could be receiving many more calls about ponds and other habitats.

Under the new “biodiversity net gain” rule, developers must compensate 110% for any damage their construction does to nature. Where the developer can’t do this on-site, it can do so through a national market for biodiversity offsets, a type of token representing a unit of newly created or enhanced and maintained habitat. Controversially, the law will allow developers to invest in habitats completely different to the ones they destroyed, raising concerns that England’s landscapes could turn into something else entirely and result in a disaster for nature.

“There’s a strong risk that developers will all focus on the cheapest and fastest habitats to restore, leading to a decline in biodiversity,” said Frédéric Hache, executive director of the Green Finance Observatory, a non-governmental organization, and lecturer in sustainable finance at Sciences Po, a university in Paris. The offsets are, in effect, “permits to destroy,” he said.

A spokesperson for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, the UK government arm responsible for overseeing the new rule, said the “rule will require most habitats to be replaced on a like for like or higher basis.”

The offset credits are comprised of “biodiversity units” whose value are calculated by factoring in the size of a habitat parcel, along with its distinctiveness, condition and strategic significance. “Distinctiveness” refers to whether the habitat is scarce or declining, and such habitats score higher relative to those that are more widespread. “Strategic significance” refers to whether the habitat is in a place where it can be connected to others like it, or if it meets particular local biodiversity objectives. In other words, as long as there’s an overall net gain based on this metric, hectares of grassland could be replaced by a newt pond — no matter the species and habitat are completely different.

There’s a lot at stake in the UK getting this right. Its biodiversity offsetting rule could influence multiple others like it. The EU is in the process of developing its own nature restoration targets and mechanisms, while negotiations are underway at the United Nations on a biodiversity equivalent of the landmark Paris climate agreement. Meanwhile, studies on similar biodiversity offsetting schemes in Canada, Australia and at a global level have found very few achieve their targets and most are unsuccessful.

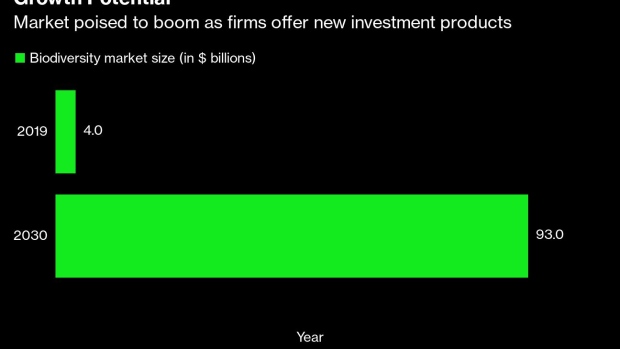

The UK government expects individual biodiversity units to fetch £20,000 on average, and estimates that the market value could reach up to £274 million per year. Among the entities looking to broker the deals are Malaysian construction conglomerate YTL’s EnTrade; a partnership between Nestlé and consultancy 3Keel called Landscape Enterprise Networks; and Environment Bank, which is fully backed by asset manager Gresham House. HSBC’s Climate Asset Management has also expressed interest. In the UK and beyond, investors are positioning themselves to capitalize on the global market for biodiversity investment products, which has the potential to grow 2,000% to $93 billion by 2030.

“We hope ultimately that biodiversity as a sector becomes recognized as an investment class and that this can drive larger pools of capital,” said Peter Bachmann, managing director for sustainable infrastructure at Gresham House. “We see a genuinely new opportunity here.”

Globally, the biodiversity crisis is rising up corporate and investor agendas as regulators, scientists and economists sound the alarm about rapid and irreversible species decline. Corporate claims of being “nature positive” or “biodiversity neutral” are increasingly featuring in sustainability reports.

Read more: Biodiversity Disclosures Set to Become Part of Company Reporting

In the UK, the new rule and broader emerging market for biodiversity offsets could engender widespread landscape change as companies seek to compensate for their harm to nature. Environment Bank estimates the market could require at least 10,000 hectares per year in England, equivalent to around 8,200 football pitches. “We have hundreds of inquiries each week, primarily from the construction sector,” said Emma Toovey, ecology director at Environment Bank. “We’re also seeing interest from the corporate market for ESG purposes, as biodiversity units used for net gain are transferable for that market too, and we can only see that increasing.”

Private sector interest in so-called ‘natural capital’ is not being welcomed in all corners, however. In Wales, farmers are competing with investment funds in farm auctions, as the latter look to acquire land for another type of environmental asset, carbon offsets, The Times reported. The National Farmers Union has cautioned against farmland conversion from food production to trees. “We cannot allow private companies to relentlessly pursue farmland in order to greenwash,” Stuart Roberts, deputy president of the NFU, wrote in a letter to the Financial Times.

Read more: This Timber Company Sold Millions of Dollars of Useless Carbon Offsets

Back on Peter’s farm, the family are still considering whether to take the newt pond offers and others like it that come in. Their primary focus is raising a dairy herd and growing crops. “There is quite a large pot of money coming for biodiversity,” Peter said. “But our core business is growing food and you don’t want to tie up your land, so you need to be careful what you sign up to.”

(Adds comment from Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs in the sixth paragraph.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.