Oct 2, 2019

‘Corbynomics’ Is More Popular Than You Think

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Jeremy Corbyn, leader of Britain’s Labour Party, is seen as an unpopular politician. But new polling shows how popular many of his radical economic policies are.

Britain will soon (though it’s not yet clear when) hold its fifth nationwide election in four years. The looming general election will be the most consequential since Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979, if not the entire postwar era. Aside from determining the direction of Brexit, the election will also decide whether Britain is run by the most radical left-wing government that the country has ever known.

Corbyn’s Labour Party will offer voters one of the most radical economic agendas anywhere in the democratic world. It will include sweeping tax increases for corporations and high earners, handing 10% of company shares to workers, a 32-hour working week, a cap on private rents, strengthened unions and plans to redistribute the assets of private schools into the state sector -- another measure that is clearly aimed at high net worth individuals. A Corbyn campaign would also include (as Labour’s 2017 manifesto did) a commitment to take key industries, including water, gas and rail companies, out of the private sector and putting them back into the hands of the state.

Clearly, the likelihood of such policies being implemented will depend on whether or not Corbyn’s Labour can win a majority or, alternatively, garner sufficient public support to lead a “progressive alliance” with the Scottish nationalists and/or the Liberal Democrats and Greens.

Some argue that all of this is unlikely for three reasons. First, the Labour Party lags well behind Boris Johnson and the Conservatives; of the last 40 polls, Labour has not led in a single one.

Second, Corbyn’s ambivalence over Brexit is helping to fuel a resurgence of support for the unequivocally anti-Brexit Liberal Democrats. According to the latest polls, one in four people who voted Labour at the last election in 2017 say they now plan to vote for the Liberal Democrats and their leader Jo Swinson. If the Liberal Democrats remain strong then this will divide remainers and, ultimately, help Johnson.

Third, Corbyn himself is incredibly unpopular. According to the pollsters Ipsos-MORI, Corbyn now has the lowest leadership rating of any opposition leader since they started conducting surveys in 1977.

Of course, there is another, competing view. Public support for Labour could rally during an election campaign, just as it did in 2017, when Corbyn started poorly but went on to bring his party its highest vote since Tony Blair’s second landslide in 2001. Corbyn and his team are making no secret of their desire to frame Boris Johnson as “Britain’s Trump,” an irresponsible Brexiteer who they will argue is the embodiment of a wealthy, distant elite.

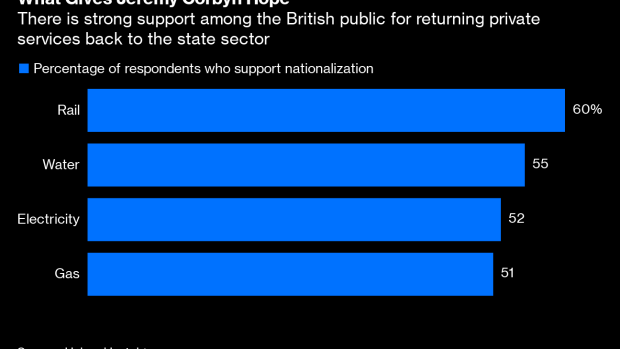

Support for Labour might also be underestimated because of something else: Many of its radical policies are more popular than people think. A new poll of a nationally representative sample of British voters for UnHerd Insight confirms a trend of ongoing and strong public support of nationalization. Overall, 55% of all voters said that they supported the nationalization of water, 52% supported the nationalization of electricity and 51% felt the same way about gas. Remarkably, 60% supported the renationalization of rail. Among Labour voters the figures were much higher: Over 70% supported putting utilities back into the public sector while over 80% wanted to see the same for rail networks.

Such numbers reflect the fact that large numbers of Brits perceive the economic system to be rigged in favor of the rich, and are incredibly pessimistic about their future economic prospects. In the shadow of the financial crisis and austerity, they still feel squeezed by low growth, the rising cost of living and often have no direct memory of earlier decades, when key industries were controlled by the state.

Nor is nationalization the only part of Labour’s radical agenda that enjoys fairly widespread public support. In recent months other work has similarly pointed to a large reservoir of latent support for a more interventionist and protectionist agenda.

For example, large majorities support a battery of policies that Corbyn will be offering people at the looming general election including: capping rent prices at the rate of inflation, increasing income taxes for the top 5% of earners, requiring businesses to reserve a proportion of seats on their boards for workers, scrapping university tuition fees, ensuring that at least 60% of Britain’s heat and electricity come from low-carbon or renewable sources by 2030, and renationalizing utilities like energy and water.

There is also clear evidence, reflected in the policies of both major parties now, that the public are tired of austerity. Britain’s National Center for Social Research points out that, for the first time since 2002, a majority of voters want taxes to increase in order to spend more on hospitals, schools and other public services, which they feel have been eroded by years of austerity.

Any election in the current environment is impossible to predict. But, as these polls show, while Corbyn himself may not be liked, his radical economic policies are more popular than many of his critics, and those in business, often think.

To contact the author of this story: Matthew Goodwin at

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Therese Raphael at traphael4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matthew Goodwin is a professor of politics at the University of Kent and a senior fellow at UnHerd Insight.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.