May 27, 2020

Covid-19 Is Going to Hasten the Demise of Many Oil Refineries

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Who needs a loss-making, inflexible oil refinery in a world where demand for petroleum has been obliterated? We’re about to find out.

When consumption of transport fuels collapsed this year because of coronavirus, much of the industry moved into survival mode, cutting processing rates and even temporarily stopping refining in some cases. While that helped prop up the industry’s margins for a while, a combination of rising crude costs and still-weak end-user demand are starting to bite.

With many oil traders and analysts expecting a slow and uncertain recovery in demand, there’s now an open question about where that leaves refineries supplying tens of billions of barrels of fuel each year. It seems likely that many of the weaker plants will be permanently shuttered.

“The Covid situation has accelerated the rationalization process that was always coming,” said Spencer Welch, vice president of oil markets and downstream consulting at IHS Markit. “It will hit Europe hardest and first. But it will also hit North America, particularly the East Coast.”

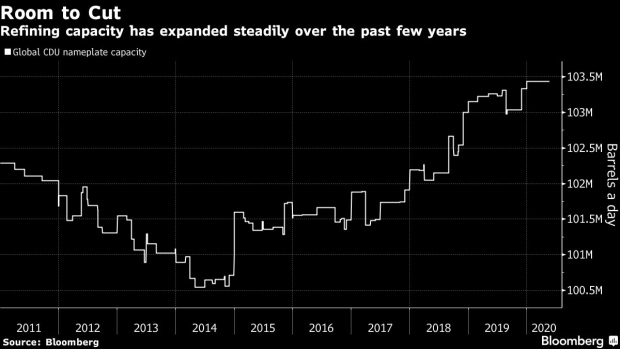

The refining industries in Europe and the U.S. have long grappled with overcapacity as bigger, more efficient plants got built in the Middle East and Asia. The expansions mean that plants making fuel in France or Belgium, for example, have found themselves increasingly competing against supplies imported from the likes of India, Saudi Arabia or even as far afield as South Korea.

In recent weeks, Asian refineries have enjoyed stronger local demand that’s kept the region’s plants busy, while a recovery in Europe and the U.S. has lagged.

While the refining industry globally has been forced to take capacity offline, the hit has probably been bigger in Europe and the U.S. than in Asia, according to Fitch Ratings. China, in particular, is a relative bright spot -- its refinery runs have recovered, and margins are being helped by a government-set floor in product prices.

The combination of a tightening crude market and weak demand is set to keep refining margins at historic lows over the coming months, researcher JBC Energy GmbH said in a note.

“In this difficult environment, efforts by the more resilient refiners, not only in Asia, to gain market share may further contribute to pushing out the most vulnerable players, ultimately leading to some pressure relief in the medium to longer term,” JBC said.

IHS estimates that Europe could lose about 2 million barrels a day of oil-processing capacity by 2025, roughly equivalent to 13%. And about half of that is attributable to the fallout from the current crisis.

But it’s not only Europe. Where they can, refiners in the U.S. are switching out of jet fuel and, to some extent, gasoline, and making more diesel. But that’s only adding to a surplus of that fuel.

America’s refiners responded to the downturn by slashing rates to a minimum and idling some gasoline-making units. Marathon Petroleum Corp., the biggest U.S. refiner, temporarily shuttered two of its refineries.

The devastation that Covid-19 has wrought on demand “is not over yet,” Tom Nimbley, chief executive officer at PBF Energy Inc., said on a May 15 earnings call, even as U.S. gasoline demand was showing signs of recovery. PBF is running its six refineries at minimum rates.

“2020 will be a tough year for the industry, and in particular for refineries with high debt and weak liquidity,” said Dmitry Marinchenko, a senior director at Fitch Ratings, which has taken negative rating actions on Marathon Petroleum, and Turkey’s Turkiye Petrol Rafinerileri AS, or Tupras.

In Europe, the most vulnerable refineries are probably the so-called simple plants -- those lacking options for reprocessing what’s left over after the key distillation process in refining, according to IHS. While the initial slump was particularly bad for jet fuel and gasoline, there have been signs of recovery. Diesel has held up better in Europe, but that’s at risk too because jet fuel is being diverted into that product.

Weak margins in the industry could last for years, said Jonathan Lamb, an analyst at Wood & Company, an investment bank. He says demand could take a couple of years to recover at best.

“In the meantime, capacity continues to increase,” he said. “Hanging on in the hope of better margins is not a smart move.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.