Sep 28, 2020

COVID spike could push Ontario, Quebec back into lockdown

, Bloomberg News

Ontario shouldn't go back to Stage 2 based on the current case numbers: Infectious diseases specialist

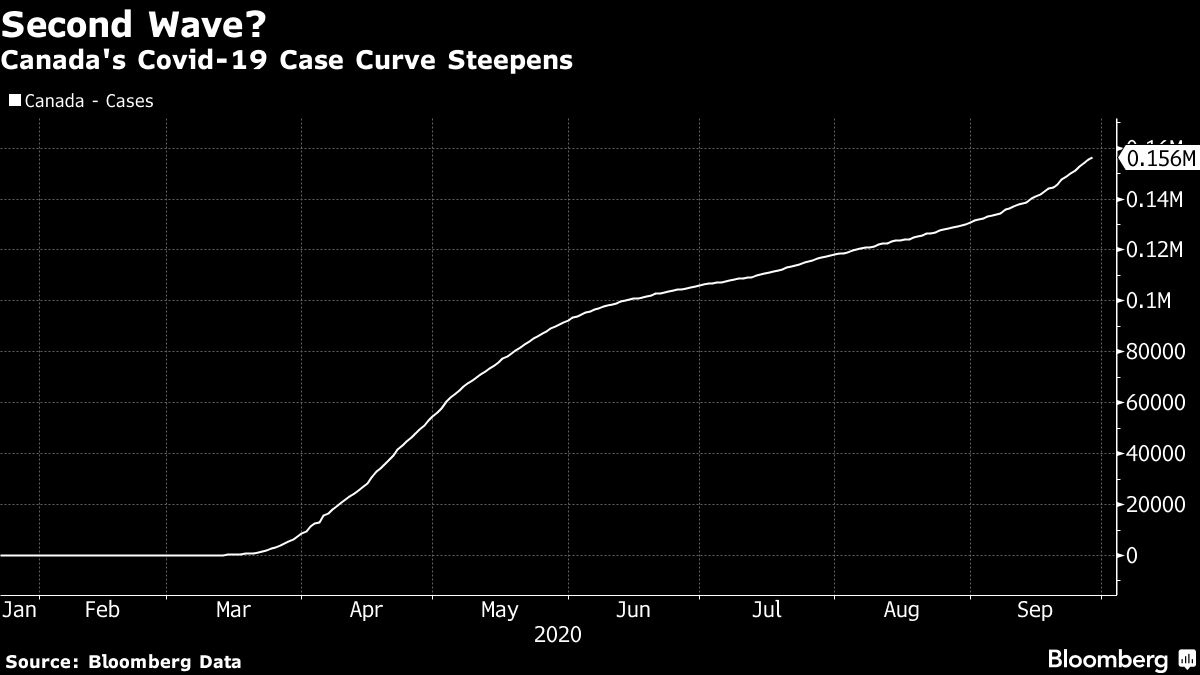

Canada’s largest provinces are bringing in new limits on activity after a spike in COVID-19 cases, threatening to short-circuit an economic recovery.

Quebec will force public places including bars, museums, cinemas and restaurant dining rooms to close from Oct. 1 to Oct. 28 in three regions, including greater Montreal and greater Quebec City. Schools and stores will remain open. The province, which has had more virus deaths than 40 U.S. states, is an epicenter of a second wave with about 5,000 active cases, a 71 per cent jump from the beginning of August.

Premier Francois Legault announced the measures Monday “with a heavy heart” and said his government is working on ways to support the businesses affected. People living in those regions also won’t be allowed to receive guests at home.

“The situation has become critical,” Legault said at a news conference. “If we don’t want our hospitals to be submerged, if we want to limit the number of deaths, we must act strongly right now.”

Ontario, the largest province with 14.7 million people, reported 700 new cases Monday, the most ever in a day, though it’s also testing far more people than it was in spring. A group of hospitals called on Premier Doug Ford’s government to revert to stricter “stage two” measures in Toronto and Ottawa, which would mean restricting or closing indoor businesses such as gyms, movie theaters and restaurants.

“It’s up to each of us. Together our collective actions will decide if we face a wave or a tsunami,” Ford said Monday at a news conference during which he pleaded for residents to follow rules and get the flu vaccine -- but did not move the province back to stage two. Earlier this month, his government reduced limits on how many people can gather in one place.

It’s a reversal of fortune for a country that avoided the summertime spike that hit the U.S. As the pandemic got worse in Sun Belt states, a largely compliant Canadian population hunkered down and wore masks.

Provincial governments, which set the rules for most companies, allowed the vast majority of businesses to open up again, sometimes with capacity limits and new sanitation rules. In Toronto, the financial capital, many restrictions were lifted on July 31.

As Labor Day neared, virus cases started to rise again. They flared in British Columbia, praised for its early handling of the crisis. Nationally, active cases have more than doubled since Sept. 1, to 12,759. Almost 95 per cent are in the four largest provinces, with the greatest problems in big cities.

Six months of restrictions left some Canadians just as restless as their counterparts in the rest of the world. Across the country, the spike in new cases is being driven by social gatherings among people in their 20s and 30s, fed up with social distancing and hoping to take advantage of the last weeks of warm weather.

ACTIVE CASES

| Province | Aug. 1 | Sept. 27 | Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 278 | 1,375 | 395% |

| Ontario | 1,319 | 4,196 | 218% |

| Quebec | 2,894 | 4,947 | 71% |

The greater concern is that COVID-19’s toehold is becoming a foothold just as the country begins its rapid slide through autumn to winter, said Colin Furness, an infection control epidemiologist at the University of Toronto. This coronavirus survives and stays in the air longer in cold, dry weather, he said -- people’s mucous membranes are less effective at filtering it out and infection rates are much higher indoors. Despite a run on fire pits and patio heaters, most policy makers are not expecting Canadians to dine outside in sub-zero temperatures.

Lower Mortality

One bright spot in the situation is the relatively low mortality rate in Canada. With the tragic exception of elder care facilities in Ontario and Quebec, where death rates soared early on, Canada’s fatality rate, per capita, is less than half that of the U.S. since the pandemic began -- roughly 25 people per 100,000 population versus 63 in the U.S.

As treatments have improved, along with better protection for the elderly and, crucially, greater testing -- and therefore identification -- of cases in younger people, so have the mortality numbers.

But while a lower fatality rate is good news, it doesn’t protect hospitals from being overwhelmed by a surge in cases, especially during flu season. And there are significant health consequences with the virus, Furness said.

“If we focus just on the death rate, eventually everyone is going to say this is no big deal,” Furness said. “We should reframe our understanding of COVID as vascular disease that causes widespread brain damage in the population.”

For policy makers and politicians, protecting the hospitals, which already have enormous backlogs of delayed surgeries, and keeping the schools open are key. But the rising case numbers threaten disruption on all fronts.

“If politicians do not have the political fortitude to reintroduce some restrictions, then our risk of sliding into something much worse -- like the U.K. or Spain -- that’s still on the table,” said Furness. Canada needs to implement rapid testing across the country, tighten definitions on “non-essential” travel and hold the line on 14-day quarantine periods for those who have been out of the country, he said.