Jul 26, 2021

Credit Suisse Brain Drain Hits Investment Bank in Top Deals Year

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- When a U.S. insurer indicated it was looking to sell its European business earlier this year, Credit Suisse Group AG executives thought they were in pole position to advise on the $1 billion-plus deal. Then a cadre of the Swiss bank’s top insurance dealmakers walked out the door.

AmTrust Financial Services Inc. went with JPMorgan Chase & Co. instead, according to people briefed on the decision, who asked not to be identified discussing private matters.

It’s a scene playing out from New York to Sydney as Credit Suisse struggles to retain its most talented advisers and risks losing out on valuable deals in one of the hottest merger markets in years. More than 40 managing directors across the dealmaking side of the business have left since a pair of scandals rocked the firm’s profits and image, including the M&A chief and five global heads or co-heads of industry teams.

The departures have especially hit groups courting financial institutions and technology, media and telecom companies, two areas of traditional strength for Credit Suisse. And of the 10 senior bankers the firm tapped late last year for an elite squad to work on the biggest transactions across industries, three have left in recent months.

Credit Suisse declined to comment.

Many top bankers are concerned about pay after the collapse of Archegos Capital Management cost the bank $5.5 billion. They also fret about the firm’s reputation after it angered asset management clients who had invested in now-frozen funds the bank offered with failed lender Greensill Capital. Credit Suisse has handed out some retention bonuses to keep top performers, but it hasn’t halted the stream of departures.

Newly installed chairman Antonio Horta-Osorio is currently reviewing the firm’s strategy as he seeks to chart a new course. But his comments have sown further uncertainty about how the investment bank in particular will emerge.

The exodus threatens the strength of businesses that have been among the top in the industry dating back decades to when the investment bank was known as Credit Suisse First Boston. And it comes as a record deluge of transactions lifted first-half profits at its biggest Wall Street rivals. With conditions ripe, competitors are flush with cash and luring away entire teams and top rainmakers. Credit Suisse is set to give investors an update when it reports second-quarter results this week.

While the exits go beyond just dealmakers, those have particular importance both because of the fees they bring in and how they fit with the bank’s broader strategy. The business doesn’t carry the risk or capital requirements of trading and tends to have high profitability. And Credit Suisse and rival UBS Group AG, while reducing their investment banks in recent years, have argued that they need to maintain advisory businesses as a service to offer rich clients and to capture deal flow opportunities. Strong investment banks are seen as a key selling point to the wealthy.

The departures present a huge challenge for top management, including Chief Executive Officer Thomas Gottstein, a former investment banker. He’s pushed, unsuccessfully, to try and keep bankers including George Maddison, the vice chairman for the insurance team, from leaving, people familiar with the matter said. While Credit Suisse has made a few hires of its own, replacing the senior bankers who have left could take years and prove costly.

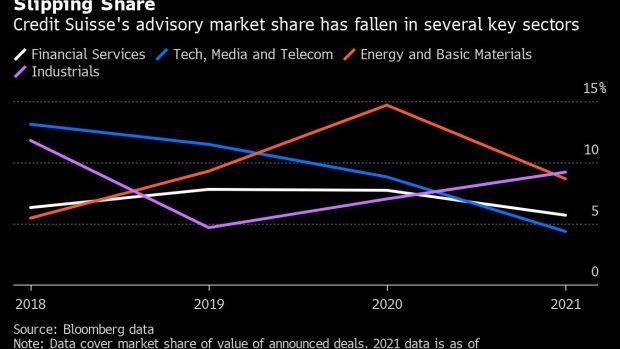

The firm clocked up about $350 billion worth of deal credits across four key coverage sectors last year -- industrials, energy and basic materials, technology, media and telecoms, and financial services -- according to data compiled by Bloomberg. They included S&P Global Inc.’s $44 billion takeover of IHS Market Ltd., Advanced Micro Devices Inc.’s roughly $35 billion purchase of rival chip maker Xilinx Inc., and the multibillion-dollar tie-up of payments firms Nexi SpA and Nets A/S.

Credit Suisse has dropped down the adviser rankings in three of those four sectors so far this year. While the missed opportunities may not show up in revenue right away as mergers often take months to complete, it could weigh on revenue growth at a time when the firm is also cutting back on risk in its trading unit.

Signs are already emerging that the bank may be missing out on deals where it might historically have expected to play a role, either due to a track record advising a company or senior connections. Australian newspapers reported that Hansen Technologies was expected to tap the firm for advice on its takeover offer from a local private-equity firm. Hansen, which has Credit Suisse’s former country head as its chairman, chose UBS.

And Credit Suisse doesn’t have a role on the $17 billion takeover bid for Sydney Airport, even though Global Infrastructure Partners is part of the consortium vying for the airport operator. GIP was co-founded by Credit Suisse banker Adebayo Ogunlesi in 2006 and has used the bank before as adviser on deals.

Alejandro Przygoda had led Credit Suisse’s financial institutions group for a decade before leaving for Jefferies Financial Group Inc. in May. Max Mesny, a specialist in fintech and payments, was credited with the most deal volume in EMEA last year, according to data provider MergerLinks. He’s leaving to join Perella Weinberg Partners. And in Australia, M&A head Kierin Deeming has left for JPMorgan.

Every managing director and rainmaker that leaves risks jeopardizing Credit Suisse’s ability to capture big fees and deals. Its bankers have brought it more than $3 billion of annual advisory and capital markets fees in three of the past four years. Analysts at Jefferies cited the talent drain earlier this month as a reason they expect Credit Suisse’s investment bank to fall short of rivals’ performance.

“We think revenues will disappoint expectations and show a sudden fall in momentum,” bank analysts including Flora Bocahut wrote in the report

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.