Jun 7, 2022

Customer-Service Wait Times Triple as Staff Shortage Vex Call Centers

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Thanks to a trio of pandemic-era shake-ups -- job vacancies, work-from-home, and chattier callers -- customer-service wait times are soaring in the US.

The average length of a service call rose by several minutes since the pandemic started, according to call-center analytics firm CallMiner. During the Covid-19 lockdowns, callers were so desperate for human contact that they started “talking about the pandemic, talking about the vaccines, talking about the political climate,” said CallMiner Chief Technical Officer Jeff Gallino.

In a 2021 study of call-center leaders that Forrester Research did for CallMiner, 68% of respondents said the phone was a new “empathy channel for customers” and 70% said their agents were dealing with more emotionally charged consumers.

Add to that endemic turnover that got worse as remote work enabled employees to easily switch to other types of jobs, and you get waiting times that probably tripled, according to Gallino’s estimate.

“Hold times have been measurably terrible,” Gallino said, adding he expects things to improve as call centers work through the hiccups. “As they staff up, this will come down.”

One silver lining: the data didn’t show much change in overall customer-service quality during the pandemic.

The Covid-19 crisis that has emptied offices nationwide has been a mixed blessing for call centers. At once, it’s made customer-service work more appealing to those who prefer to work from home, but it’s also made it easier for call-center employees to jump to another place.

Worker turnover has always run high in customer service, around 50% a year, said Jeff Christofis, who oversees staffing giant Kelly Services’ contact center unit. During the pandemic, it has swelled to at least 80% -- and in extreme cases to as much as 300%.

There are roughly 3 million customer-service workers nationwide. Before Covid-19, as many as 90% worked in office settings, Christofis estimated. He sees the industry settling into a 50-50 split among in-person and at-home workers, but for now, the workforce is largely working remotely and resisting change.

Among them is Timarie Czichas, a 55-year-old from the Phoenix area whose small business was wiped out in the pandemic. Her arthritis flared up and made working outside the home unfeasible, so she counts herself fortunate to have landed a remote customer-service job with used-car dealership company CarMax Inc.

“I enjoy talking with and helping people, so I feel very blessed to have this position,” Czichas said.

Claire Roma, a 28-year-old from the Detroit area, took a work-from-home customer-service job with a meal-delivery company in January, happy about the good pay and “insanely good” health-care benefits. She says she doubts she could handle the stress of a commute, office culture and occasionally cranky customers if it were an in-person job.

Unfilled Positions

In suburban Atlanta, it has taken Chris Sperry two to four weeks to replace a remote position, but seven to nine weeks to fill an in-person spot. Sperry oversees the Georgia Medicaid operations of Gainwell Technologies, which manages Medicaid programs for various states nationwide, and he’s obligated to at least have some staff working on-site.

On a recent morning, the 10th and 11th floors of the glassy office tower where Gainwell has its contact and technical-support centers were eerily quiet, save for a half dozen agents who’d come in to work the phones. For now, most agents are free to work from home, but he worries about mass departures among his 110-person call center staff if they’re asked to report to the office. He already has around 25 unfilled positions.

Call-center managers are responding by hiking pay and trying to build company culture despite seldom seeing their workers. Pre-Covid, customer-service representative pay averaged around $14 an hour, and there was little variation in wages among the big business process outsourcing giants, or BPOs, that employ tens of thousands of agents. So, there was little reason to switch jobs, Gallino said.

But with workers in short supply during the pandemic, some BPOs bumped up pay to $17 an hour on average, and to $19 in some cases. Remote work meant people could jump ship without getting out of their pajamas.

“If you’re sitting at home and you’re not happy with your job, you’re, like, two clicks away from filling out an application,” said Bryan Ennis, CarMax’s vice president of customer-experience centers and customer relations.

CarMax is trying to build rapport among its far-flung crew by hosting more employee icebreaker events and volunteer opportunities with charities, Ennis said. Turnover peaked a year ago and has been falling lately, he said. Other companies are setting up Facebook-style company intranet systems so work-from-home staff can vent and build rapport among each other.

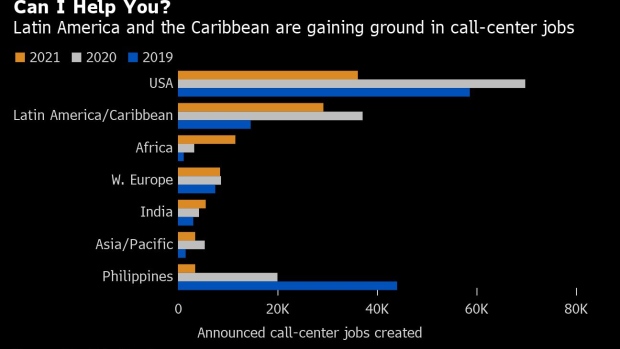

Some companies give up and move abroad. The industry has gone through periodic waves of offshoring and onshoring for decades, with massive shifts to India 20 years ago and to the Philippines around 2010, although many jobs came back to the US because of quality concerns, said King White, who leads Dallas-based Site Selection Group.

He’s seeing the start of a new wave to Latin America and Jamaica as companies get fed up with the lack of people.

“I’m talking thousands and thousands of jobs,” White said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.