Jul 10, 2019

Defend Fed Independence. You Might Need It Someday.

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Federal Reserve independence is on trial in Washington again.

President Donald Trump’s top economic adviser, Larry Kudlow, broke with decades of economic orthodoxy on Tuesday when he agreed with the prominent supply-sider Arthur Laffer that Fed independence is undemocratic and that monetary policy should be handled by the Treasury Department or Congress.

Then on Wednesday, Maxine Waters, Chair of the House Financial Services Committee, urged Fed Chairman Jerome Powell to resist efforts by the White House to compromise his institution’s autonomy.

Like most economists, I consider Fed independence to be a valuable tool. At the same time, the conservative Laffer raised important concerns, many of which are echoed on the left by adherents of modern monetary theory.

Supply-side theory emerged in the 1970s, and argued that a combination of tax cuts and relatively low interest rates could bring down inflation and grow the economy. Supply-siders waved away concerns about deficits.

Modern monetary theory argues that government spending should be used to sustain growth and that any resulting deficits should be financed by monetary policy. MMT waves away concerns about inflation.

Most of the commentary around these theories focuses on their lack of concern about deficits. That lack of concern, however, is a product of their rejection of central bank independence. With the central bank at its disposal, the White House could always control the high interest rates that deficits encourage.

Both supply-siders and MMT adherents justify this stance by arguing that monetary policy is a tool of public policy that should not be controlled by a technocratic committee of economists any more than foreign policy should be controlled by generals.

This is an unorthodox stance but it deserves to be taken seriously.

The first is democratic accountability. The reason for creating an independent Fed is to reduce the influence of democracy on monetary policy. The thinking is that democratic bodies and the public are likely to be shortsighted, ignoring long-term risks like inflation that could follow politically popular tax cuts or spending increases. Instead, monetary policy should be run by experts trained to recognize those risks and address them.

When the Fed meets to discuss interest-rate changes only seven — the chair and six governors — out of a total of 19 decision makers are appointed by the president and approved by the Senate. The other 12 are regional Fed presidents who are appointed by their respective boards. The Fed’s unusual voting structure requires seven of the 12 presidents to sit out each vote, theoretically giving the White House appointees a majority.

Currently, however, two governorships are vacant, meaning that the regional presidents have as much voting power as the federally appointed chair and governors. Nor is this situation unusual. When Trump came into office, two of the governorships were vacant and two more governors resigned soon after.

This structure implies that despite Trump’s efforts to pressure the Fed to raise interest rates, neither the White House nor Congress has much power to compel the Fed to do anything.

The Fed was set up this way so that it could take a long-term view without being influenced by the next election or the whims of the party in power.

As Laffer pointed out in a CNBC interview on Monday, however, it also removes a powerful tool that governments have for making policy. As a supply-sider, Laffer believes that the Fed should lower interest rates to accelerate economic growth, encourage investment and make the most of the recently passed tax cuts.

I generally agree. The Fed’s rapid pace of interest-rate increases combined with the Trump’s haphazard trade policy have increased uncertainty and caused businesses to pull back on investment at precisely the moment when it's most advantageous for them to plow ahead. As a result, the U.S. economy won’t get a clean test of the power of tax cuts to spur long-term growth.

Unlike Laffer, however, I am willing to swallow this bitter pill because the same institutional structure that prevents supply-side economics from being fully implemented also constrains MMT.

MMT is risky because it overlooks the long-term costs of increased government spending. Spending speeds up economic growth quickly and give politicians concrete projects they can tout as signs of success. The costs come later, sometimes decades later, as the return on investment from projects chosen for political popularity turns out to be less than expected. The larger and more expansive the political vision, the more difficult it is to abandon even in the face of disappointing results.

MMT advocates have sweeping economic plans like the Green New Deal and job guarantees for all Americans. Like supply-side economics, there is no way that these plans could be put into place unless the Fed plays along.

This similarity between the supply-side and MMT approach to the Fed reflects a deeper philosophical kinship. Both schools of thought believe that the U.S. economy has untapped productive capacity that aggressive coordination between monetary and fiscal policy could reach.

The difference is that supply-siders are attempting to jump-start the private sector while MMT is supplying a rationale for expansive government programs like universal health insurance and college tuition subsidies. Another difference is that while supply-siders are waning in influence, MMT is on the rise.

This reflects a change in circumstances. Supply-side economics was born in the 1970s amid rising taxes, slowing job growth and accelerating inflation. MMT is coming to prominence in an era of moderate taxes and low inflation but stagnant wage growth.

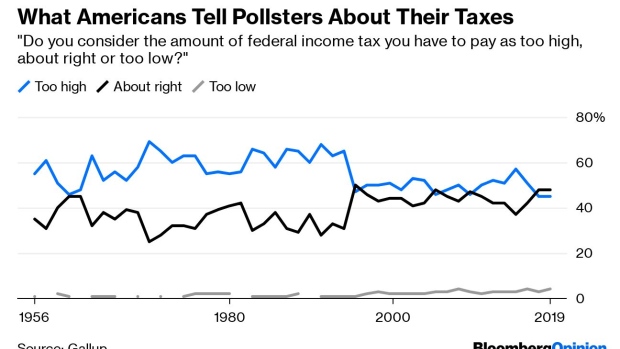

In the 1970s and 80s, according to the Gallup Poll, most Americans viewed taxes, particularly income taxes, as too high. Today income inequality is a more salient concern.

Both then and now, however, the problem is complex. Advances in technology, changes in international trade, the entry and now exit of the baby-boom generation from the workforce wreaked slow havoc across the economy both in the 1970s and over the last 20 years.

It's natural then that more heterodox economists, as well as the general public, would yearn for a more comprehensive solution.

In 1980, public dissatisfaction reached a boiling point and voters elected President Ronald Reagan, who was ready to implement supply-side economics’ radical prescriptions.

The Fed, however, forced Reagan to pay for his priorities with surging interest rates and a sharp recession. That limited his administration’s ability to implement its ideas but also ensured that the nation would not veer too far off track.

If a Democratic president embraces MMT, it will be crucial for an independent Fed to make sure that the potential costs of those policies are transparent, not papered over and left for future generations.

To contact the author of this story: Karl W. Smith at ksmith602@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Karl W. Smith is a former assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina's school of government and founder of the blog Modeled Behavior.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.