Mar 9, 2020

Deflation Is the Biggest Fear of Leveraged Bond Markets

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s often said that inflation is the bogeyman for bond traders. Indeed, accelerating price growth diminishes the value of each fixed interest payment over the years. Investors would be better off buying assets that increase along with prices, like real estate or equities, in theory.

This week, bond traders are learning that the prospect of deflation can be just as painful.

The benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury yield tumbled by as much as 45 basis points on Monday to as low as 0.3137%. That’s more than 100 basis points below the record level of 1.318% that stood as recently as last month. Sure, anyone who owned U.S. Treasuries heading into 2020 has benefited from the incredible rally. But it leaves future investors with a grim reality of rock-bottom returns, putting the U.S. closer than ever to the likes of Germany and Japan.

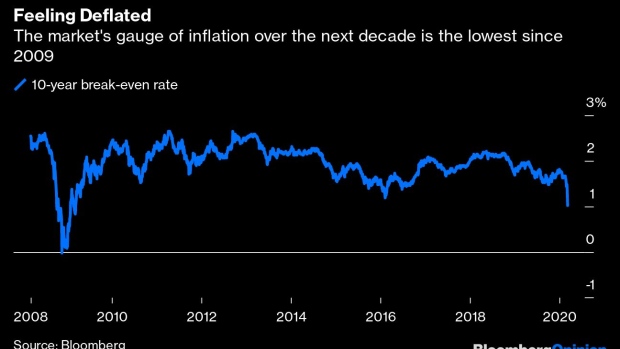

Last week, investors flocked to Treasuries purely as a way to protect against a swift slowdown in global economic growth because of the coronavirus outbreak. This week it’s something more. The price of oil crashed more than 30% after Saudi Arabia declared a price war and the OPEC+ alliance shattered. So too did break-even rates, which are the bond market’s measure of inflation expectations. The 10-year rate collapsed more than 30 basis points, the steepest decline since November 20, 2008, to about 1 percentage point, the lowest since March 2009. The five-year rate is 0.8 percentage point and the two-year rate is less than 0.5 percentage point.

That’s bad news for the Federal Reserve, which is desperate to get inflation consistently at or above its 2% target after years of failing to do so. While oil prices are historically volatile, a shock of this magnitude can’t be dismissed by simply focusing on the “core” measures that exclude energy and food prices. It will reverberate through Main Street and Wall Street alike.

The sharp drop in oil prices is even worse news for credit markets. The Markit CDX North America High Yield Index, which tracks the cost of insuring against defaults, surged on Monday by 145 basis points, the largest increase ever in data going back to 2012. It’s within striking distance of the highest level on record. The investment-grade fear gauge jumped by the most since Lehman Brothers crumbled.

More specifically, significantly lower oil prices have immediate consequences for speculative-grade energy companies. At the end of last week, their yield spread widened to 1,080 basis points, up from just 612 basis points in January. It’s only going to get worse, and the spread could soon reach a record high, judging by recent trading. A Chesapeake Energy Corp. bond maturing in 2025 with an 11.5% coupon came into 2020 at a price just below 100 cents on the dollar. The same security, with a composite credit rating of triple-C, traded at 27 cents on the dollar on Monday.

Investors are even losing confidence that some companies will survive the next year or two. Antero Resources Corp. debt due in November 2021 plunged 37 cents on Monday to 46.5 cents, while Whiting Petroleum Corp. securities maturing in March 2021 fell 25 cents to a mere 20 cents. There will be bankruptcies and defaults, full stop.

The most scary prospect for bond traders is that this deflationary spiral ensnares other parts of the credit markets that are leveraged to the brim. It’s no secret, for instance, that the universe of triple-B rated corporate bonds has expanded to more than $3 trillion from $800 billion at the end of the last recession. Borrowing costs have remained historically low in the post-crisis era, creating the incentive for blue-chip companies and risky upstarts alike to finance themselves through debt. Carrying a vulnerable balance sheet can work when inflation is low but steady along with economic growth and when the credit markets are wide open for business. It’s an open question whether any of those assumptions still hold.

Bond traders expect the Fed will do what it can, up to and including cutting its key short-term rate all the way back to the lower bound of 0% to 0.25% in short order. Such a move, in theory, would spur inflation. I’m skeptical, judging by the years of stagnant price growth in Europe and Japan. So too, apparently, are the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan. There’s a reason that neither one is in a rush to drop interest rates further into negative territory.

As Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Investment Management told me last week, “when the short rates start coming down toward zero, even before they get to zero, you reach a reversal point and the counterproductive effects of the lower rates offset the beneficial effects of having a lower cost of borrowing.”

Banks are one such industry feeling the pinch. They struggled enough with short-term rates near the zero bound and longer-term yields around 2%. How are they supposed to earn net interest income now, with the 10-year yield at 0.5%? Investors aren’t waiting to find out: The KBW Bank Index plunged about 10% on Monday.

With the coronavirus outbreak, there was always the feeling that maybe it wouldn’t be as bad as the worst-case scenario. The plunge in oil prices appears to have more staying power.

Whether that one-two punch brings about outright deflation remains to be seen. But it’s looking more likely than any point in the past decade, which is an ominous sign for bond markets of all stripes. Flocking to the haven of Treasuries provides almost no income. The reach-for-yield trade is quickly unraveling in the riskiest debt. One of the cornerstones of the longest expansion in U.S. history — a benign corporate default rate — no longer looks so sturdy.

The bond markets have cracked. Any further move toward deflation would most likely create a chasm.

To contact the author of this story: Brian Chappatta at bchappatta1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.