Aug 21, 2019

Democrats Should Care More About Russia

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When the poll-analysis website FiveThirtyEight surveyed the Democratic presidential candidates to get their views on key foreign policy issues, it decided not to ask about Russia, because it couldn’t formulate a provocative question on the subject. That’s a problem — not for FiveThirtyEight, but for the Democratic field.

“It’s a safe bet that any of the Democratic candidates, if elected president, would be more critical of Russian President Vladimir Putin than President Trump has been,” FiveThirtyEight’s Perry Bacon Jr. wrote, “but it’s hard to design a question that would illustrate the differences between the candidates on that subject. So there are some major foreign policy issues (like how the U.S. should deal with Russia) that are not represented.”

Some of the questions the survey did ask, however, found no differences among the candidates, either. For example, all 15 who answered the questionnaire have said they favor ending U.S. military involvement in Yemen and repealing the 2001 congressional authorization for troop deployments wherever a president perceives a terrorist threat. So why is it more difficult to ask a meaningful question about Russia?

The problem, I think, is that a kind of Pavlovian reflex has formed in American political circles since 2016, when Russian trolling and hacking operations against the Democrats were first widely reported. Years of “Russiagate” and unrealistic expectations from the Mueller investigation have strengthened it. Now, whenever Russia is mentioned, the associative chain immediately drags up “Russian election interference” and “Trump is a Putin stooge.”

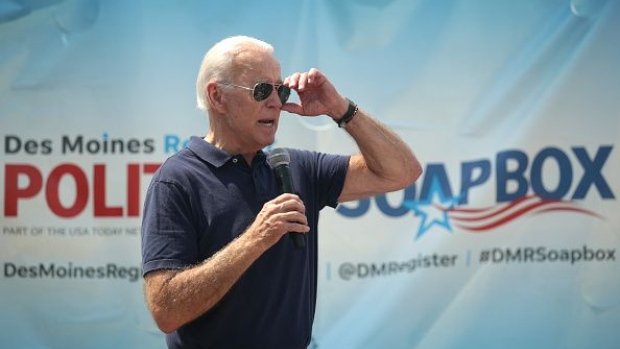

OnTheIssues, an organization that tracks politicians’ publicly expressed positions, includes Russia among its topics. Most of the Democratic candidates have said something about Russian attacks on U.S. democracy. Some of their claims — including those from Joe Biden about Putin “undoing elections” in the U.S., Hungary and Poland — are too outlandish to even start unpicking.

As Samuel Greene, director of the Russia Institute at King’s College London, wrote in a Twitter thread on the subject, Russiagate turned Russia from a foreign policy issue into a U.S. domestic one.

“As a result,” Greene wrote, “all of the oxygen has gone out of conversations about Russia’s ongoing war with Ukraine, about the occupation of Crimea, about the challenges posed to the future of the European project (in which we also have a stake), about the Balkans, about gas pipelines....”

One could add more issues to Greene’s list. How about Russia’s increasingly tight relationship with Saudi Arabia, based on their ability to set the oil price together? Russia’s bid for dominance in the Arctic? Russia’s asymmetrical responses to U.S. sanctions, like its de-dollarization, which is setting an uncomfortable example for other developing countries? Russia’s development of new weapons meant to breach U.S. anti-missile defenses? And, while we’re on the subject, how about arms control, an area in which a major U.S.-Russian treaty has just collapsed?

The FiveThirtyEight survey shows that 12 out of 15 Democratic candidates want to cut U.S. defense spending. But Russia-related issues should serve as a litmus test of that anti-war stance. How would these candidates respond if Russia moved to swallow up Belarus? Would they sit on their hands if Russia closed what it calls the Northern Sea Route for U.S. shipping? How would they react to a Russia-instigated coup in one of the African countries where Russian mercenaries, supplied by a Putin crony, have recently established a presence?

Thanks in large part to Donald Trump, prevented by Russiagate from pursuing any coherent Russia policy, and to the previous three American presidents, who tended to write off Russia as a waning regional power, the U.S.-Russia relationship has become not just adversarial but also deeply dysfunctional. Any post-Trump U.S. leader will face a dilemma: Should he or she take an implacable stance while waiting for Putin to die and his system to collapse — or pursue an active Russia policy aimed at least at laying down basic rules of interaction, perhaps even locating common interests? (For example, both Russia and U.S. allies recently welcomed a government change in Moldova.)

It’s difficult to ponder this dilemma amid the Russiagate scenery, which stagehands appear to have forgotten to put away. A responsible leader can’t really avoid it, though, especially not after the election. But then, the winning candidate — should Trump be displaced in 2020 — may have to rethink most of his or her current foreign policy positions, because Russia has a hand in every one of the global crises in which the U.S. is involved, including in North Korea, Venezuela, Afghanistan and China.

Sooner or later, candidates and voters alike will have to wake up to the real Russia issues; hacking and propaganda are nowhere near the top of the list.

To contact the author of this story: Leonid Bershidsky at lbershidsky@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mary Duenwald at mduenwald@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.