Jul 7, 2019

Denied Iran's Oil, Syria Has Few Options But Russia

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The noose strangling the flow of oil to Syria tightened a notch last week, when British Royal Marines boarded a tanker carrying Iranian crude into the Mediterranean Sea through the Strait of Gibraltar. With Syria’s Iranian supplies halted, the flow will have to come from somewhere else, and the alternative is troubling.

The Very Large Crude Carrier Grace 1 loaded a cargo of Iranian oil from the Kharg Island terminal in mid-April and set off on a long voyage around the southern tip of Africa to the eastern Mediterranean. The ship was apprehended because it was believed to be heading to a refinery that is ultimately owned by Syria’s ministry of petroleum, an entity subject to European Union sanctions.

The journey from Iran to Syria around Africa is about 14,500 miles (23,300 kilometers), compared with about 4,100 miles via the Red Sea and Suez Canal. Why take such a circuitous route? Because Iranian crude is not accepted by the owners of the Sumed pipeline, which crosses Egypt to link the Red Sea to the Mediterranean. It is also banned from the Eilat-Ashkelon pipeline across Israel, originally built with the express purpose of carrying the Persian Gulf nation’s output to the Mediterranean.

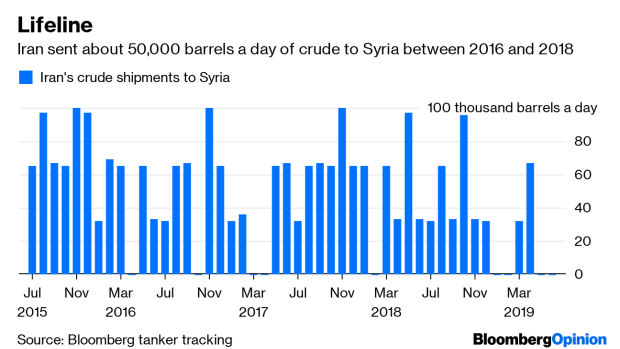

More recently, ships carrying Iran’s crude to Syria also seem to be prevented from using the Suez Canal. That looks to be a new development, since the oil trade between the two countries between 2016 and 2018 via the waterway averaged 50,000 barrels a day. All of those ships involved in that transport that have not been scrapped or sold appear on a list of vessels undertaking sanctionable activity published in March by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control.

The fate of one of those ships, the Suezmax tanker Sea Shark, is instructive. It was hauling a cargo of around 1 million barrels of Iranian crude when it arrived at the southern approach to the Suez Canal at the end of November, but turned back a day later, according to tanker tracking data compiled by Bloomberg. It then spent nearly five months anchored off the Egyptian coast before returning to Suez in late April. It is a still there and it is still full of oil. Prior to its interrupted voyage, the ship had made at least 11 journeys in 2017 and 2018 carrying oil from Iran to Syria.

This doesn’t mean Iran’s crude is completely forbidden in the waterway, since ships heading to Turkey are still able to pass. But it does mean that Syrian-bound ships carrying its cargoes have to rely on the much longer route around Africa and that a larger ship would make the journey more economic – the Grace 1 can carry twice as much oil as the Sea Shark. But that route passes through European Union waters as ships enter the Mediterranean and it was here that the Grace 1 was impounded. The government of Gibraltar has denied the claim by the Spanish Foreign Affairs Ministry that the action was carried out at the request of the U.S.

If Syria can’t get Iranian crude via the sea, what about by land? That will be difficult. U.S. allies control most of the oil-producing territory in Syria itself, while American forces straddle most of the crossings from Iraq into Syria, which might have been used to create an overland route for Iranian output.

Syria clearly needs to import oil. Aside from all the normal reasons, President Bashar Al-Assad has a war to fight. Since sanctions have severely constrained his universe of potential suppliers, he has little recourse but to look to his supporters.

If the smuggling routes set up by ISIS during its now-defunct caliphate to export oil from Syria are not now operating in reverse, perhaps they soon will be.

Or, perhaps some of the fuel delivered to keep Russian military aircraft and vehicles operating in Syria could find its way to the Syrian state.

The Syrian government has two big oil-producing friends, Iran and Russia. With the routes from the first apparently closed, it may have to turn to the second. This presents a new host of potential risks. Impounding an Iranian ship in the Strait of Gibraltar is one thing. Stopping a Russian ship in the Aegean Sea is quite another.

--With assistance from Elaine He.

To contact the author of this story: Julian Lee at jlee1627@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at jryan13@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg. Previously he worked as a senior analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.