(Bloomberg) -- To understand German banks’ lost decade, start with a now infamous birthday dinner for then-Deutsche Bank AG chief Josef Ackermann, held in April 2008 by Chancellor Angela Merkel.

The menu was inconspicuous, schnitzel and asparagus along with a $10 white wine. But the public outcry that followed, after the government was forced to support the industry with bailouts and vouch for savers’ deposits, held a key lesson for Merkel early on in her tenure: there’s little to gain in German politics from being seen as too close to the country’s top bankers.

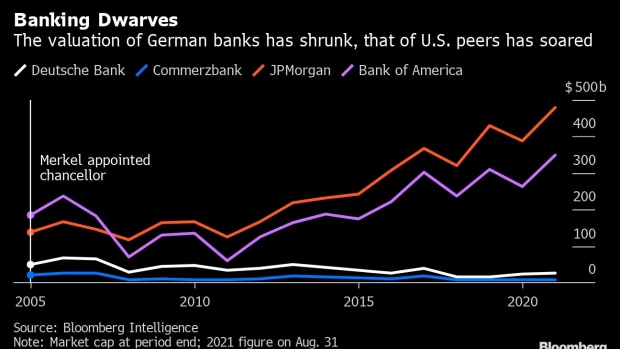

As her era ends this month, Frankfurt’s once-powerful investment banks have been diminished by years of negative interest rates and tighter regulation that Merkel helped drive. How they will emerge from that long decline depends not least on who will take over and whether the next chancellor can complete a key project that has remained unfinished: Europe’s banking union.

The frontrunner, Olaf Scholz of the left-leaning Social Democrats, has been an unlikely ally of Germany’s large banks as finance minister under Merkel. He brought on a former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. executive as adviser and backed merger talks between Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank AG when both lenders struggled with their turnaround plans. He also started a fresh effort to revive negotiations about a joint European deposit insurance, the missing leg of the bloc’s banking union.

But his hands-on approach has yielded few results -- in part, say people familiar with the matter, because of a lack of enthusiasm by Merkel, a member of the conservative Christian Democratic Union who has kept lenders at arm’s length since being forced to rescue several during the financial crisis.

The chancellor championed regulation that prompted institutions to dial back risk and focus on the bread and butter business of lending, but she failed to create a functioning single market for banking services that would have made it easier for Europe’s investment banks to compete with Wall Street.

“Merkel and her governments saw the banking sector as a servant to the industrial sector,” said Axel Wieandt, a former Deutsche Bank executive who went on to lead Hypo Real Estate Holding AG after its bailout. “The banking sector is now in better shape in terms of capital and liquidity buffers, but when it comes to competitiveness, German banks haven’t caught up.”

Hypo Real Estate’s near-collapse in 2008, along with the worsening credit crisis, forced Merkel to come out with a public statement guaranteeing all savers that their deposits were safe, a key moment that helped shape her resolve to pursue stricter bank rules. Merkel set the tone for Germany’s support of international standards for banks to hold more capital with which to absorb losses, as well as the establishment of a European fund for winding down failed lenders.

While Wall Street banks also had to contend with stricter and costlier regulation, firms like JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. won market share from Europe’s investment banks after the U.S. forcibly recapitalized major lenders in the financial crisis. Under Merkel’s stewardship, banks took longer to build up their financial reserves, and they weren’t able to consolidate in a meaningful way beyond national deals.

Europe also had a longer hangover because the ensuing sovereign debt crisis, which put a spotlight on the “doom loop” between heavily indebted governments and the banks that held their bonds. In 2012, the region’s leaders decided the answer was a banking union that could raise the bar on oversight, jointly handle failed lenders and pool protection for deposits. But that final leg hasn’t been completed because of disagreements over how to tackle risks.

“Germany took a pretty half-hearted approach to banking union,” said Valeriya Dinger, a professor of economics specialized in banking at the University of Osnabrueck. “Merkel took action in the 2008 crisis, but pretty quickly it became clear that this isn’t an industry she has a burning interest in.”

People who have worked with the chancellery say the events after the Ackermann dinner convinced Merkel that business executives, and bankers especially, were fair-weather friends. The tenuous nature of Ackermann’s loyalty to the chancellery was on display later in 2008, when he said that it would be “a shame” to accept state aid. The comments were criticized by German lawmakers as unhelpful while the government sought to stabilize the banking sector.

To be sure, Germany’s large banks also had a hand in their own decline. Deutsche Bank’s aggressive expansion as a global investment bank landed it with the highest legal bills of any European lender, and Commerzbank’s foray into shipping loans and commercial real estate saddled it with soured debt. For years, both banks pursued piecemeal overhauls that failed to decisively cut costs.

In 2019, with turnaround efforts at both lenders stalling, they held merger talks that were backed by officials in Scholz’s finance ministry, which oversees the government’s Commerzbank stake. But inside the chancellery, there wasn’t much enthusiasm to push for a deal, people with knowledge of the matter said. The negotiations eventually fell apart.

Scholz also sought to end a years-long impasse in discussions over European banking integration by saying Germany was ready to consider a form of joint deposit insurance. But the proposal failed to gather much support in Berlin, which has long been concerned that the mass of small German savings and cooperative banks could be on the hook for risks at lenders in southern Europe.

Merkel’s designated successor as candidate of the CDU, Armin Laschet, has given little indication that he’d deviate from viewing the banking sector primarily as a source of credit for industry. And with pressing challenges like climate change, the pandemic and the debacle in Afghanistan, banking regulation has taken a backseat for other candidates in the election.

Should he win, Scholz would have to overcome that indifference, not only at home but across Europe.

Banking union “is a topic that can only succeed if it has political priority,” he said last week. “I for one am prepared.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.