Jun 12, 2018

Does the World Need Another Megadeal?

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Three years and more than $3 trillion worth of megadeals later, investors may well wonder if bigger is better.

Shares of Boston Scientific Corp. spiked 7.4 percent on Monday after the Wall Street Journal reported that fellow medical-device maker Stryker Corp. had offered to acquire it. It's unclear how Boston Scientific feels about a deal, if in fact there's one on offer. Following the report, shares of both companies were halted for "news" that ended up being a Boston Scientific statement acknowledging the story and saying it doesn't comment on speculation. Cool.

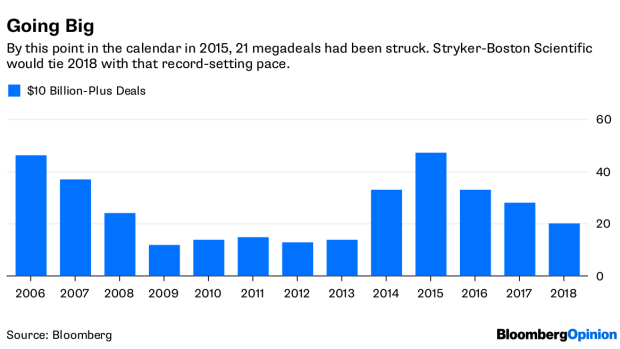

On average, analysts estimate Boston Scientific could command $39 a share in a takeover, implying an almost $60 billion deal including debt. Amazingly, that would be only the third-biggest acquisition announced this year, trailing Takeda Pharmaceutical Co.'s $80 billion bid for Shire Plc and Cigna Corp.'s nearly $70 billion purchase of Express Scripts Holding Co. All in, there have been 20 megadeals ($10 billion-plus) in 2018, essentially tied with the record pace set in 2015.

This flurry of outsize dealmaking has generally been predicated on the idea that scale is needed to offset shrinking margins as business models are upended by new entrants and digital strategies. A Boston Scientific-Stryker tie-up would be a prime example. It's essentially a bet that bigger medical-device makers have more negotiating power with hospitals and are better positioned for a consolidating health-care environment. AT&T Inc.'s $109 billion purchase of Time Warner Inc. rests on similar logic (a verdict on the U.S. Justice Department's effort to block that combination is expected on Tuesday afternoon).

The weaknesses these deals are trying to shield are real, but megamergers aren't always the fix they're designed to be. Bigness can stifle innovation (see, Kraft Heinz Co. and Allergan Plc).

For those in consolidating industries, if everyone is getting bigger, the yardstick just moves and no one gains much of an advantage at the negotiating table. Perhaps most importantly, customers often don't actually want a bundled basket of products. They like having a wide variety of options and the ability to piece together systems via different suppliers. Usually, they face profit squeezes of their own.

United Technologies Corp.'s $18.4 billion takeover of landing-gear maker Goodrich Corp. in 2012 is instructive in this regard. The consolidation allowed it to cut costs, but it's debatable how much negotiating heft it gained. After United Technologies balked at demands for price cuts, Boeing Co. handed a 777X landing-gear contract to small Canadian manufacturer Heroux-Devtek Inc. instead. Grappling with a flagging stock and weak global growth, CEO Greg Hayes nevertheless decided to try the same strategy and announced a $30 billion takeover of Rockwell Collins Inc. last year. I'm skeptical it will work as Boeing continues to turn the screws and ramps up its effort to make and service more plane parts of its own.

Back in the medical-device industry, Medtronic Plc's $53 billion takeover of Covidien in 2015 should be flashing even bigger warning signs for Stryker. The deal was a tax inversion, but those benefits have faded in the wake of the new U.S. legislation. In fact, it’s kind of been a dud. Medtronic has noted that a broad bundling of products for hospitals isn't really a thing yet, while Stryker and Boston Scientific have actually talked up the importance of focusing on fast-growing niches rather than sheer size, says Jefferies analyst Raj Denhoy.

What's most interesting to me is that people like Denhoy are willing to be skeptical about the merits of a megacombination. That was rarely the case in the heyday of 2015. You also see this from investors. Stryker shares fell about 5 percent on Monday and continued their decline Tuesday. Comcast Corp. has taken a beating amid speculation that it could try to disrupt Walt Disney Co.'s $66 billion acquisition of 21st Century Fox assets. As my colleague Tara Lachapelle notes, it doesn’t really matter what Comcast shareholders think, but elsewhere, investors may start forcing companies to come up with a more creative solution than a megamerger for their weak spots.

Stryker management may want to think about that.

To contact the author of this story: Brooke Sutherland at bsutherland7@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.