Apr 6, 2020

Dollar Squeeze Worsens in Lebanon as Banks Restrict Withdrawals

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

Lebanon’s foreign-exchange crisis, which prompted the government to default last month on its Eurobonds, is intensifying.

Local banks have reduced the amount of dollars customers can withdraw from their accounts and even forced them to accept conversions into the local currency in some instances. Two of the largest have almost stopped dispensing foreign exchange entirely, while the central bank has greatly cut its supply, said senior bankers, who didn’t want to be named.

The shortages of hard currency have already led to a deep recession and crippled many businesses as they struggle to import essential goods. The coronavirus pandemic and a nationwide lockdown to stop its spread are adding to the problems, with Lebanese lenders having closed most of their branches.

The Arab country has suffered net capital outflows every month since July, according government data, as the large diaspora that used to prop up the banking system stops sending remittances. Some lenders’ correspondent banks are cutting back on services as dollars run dry, according to the bankers.

The central bank did not respond to a request for comment.

Lebanon’s default on $31 billion of Eurobonds removed one of the last remaining sources of foreign exchange for local banks. Many of them relied on the interest and principal from those to service their clients’ dollar demands.

The government has yet to begin formal restructuring talks with creditors. It decided against repaying a $1.2 billion bond last month to save what’s left of its reserves for imports such as food, medicine and fuel.

Unpegged

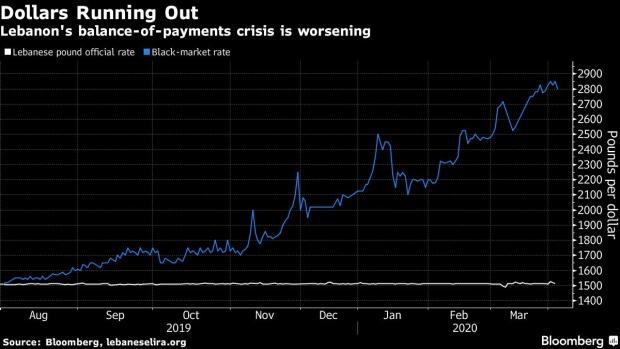

The Lebanese pound has plunged almost 25% on the black market this year to 2,800 per dollar, according to lebaneselira.org, a local website. It’s now 46% weaker than the official rate of around 1,510, which has been pegged for decades.

That’s causing inflation to accelerate and it could reach 25% this year, the government said in a presentation last month. The economy may contract by 12% from 2019, it said.

While the central bank has not said whether the peg will be formally removed, it instructed lenders last week to pay small dollar depositors in pounds at a so-called market rate, rather than the official one. It has not disclosed what the rate will be.

“An official devaluation looks increasingly likely,” Carla Slim, a Standard Chartered economist for the Middle East, North Africa and Turkey, said. “Restructured debt would be assessed in the context of the new” exchange rate, she said.

The government has asked the International Monetary Fund for technical advice. But most senior politicians are against a loan from the Washington lender, given that Lebanon would probably be required to raise taxes and cut subsidies.

Without some form of external funding, the ability of Lebanese banks to meet their foreign-currency obligations “is in serious doubt,” according to Fitch Ratings.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.