Feb 14, 2019

Don’t Like Buybacks? It’s Harder to Bet on the Flip Side

, Bloomberg News

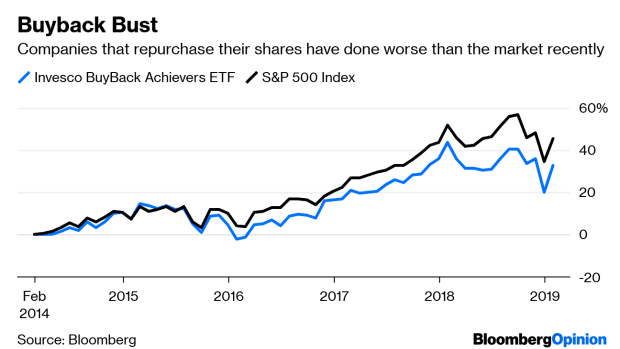

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Senator Marco Rubio has joined the buybacks-are-bad-for-America bandwagon, calling for a new tax that would neutralize the advantage repurchases have over dividends. The perceived advantage that buybacks have for investors might have gone away a while ago, but it turns out it’s harder to bet that way.

Earlier this week, Bloomberg Intelligence compared the stock performance of companies that have devoted more of their earnings to share buybacks with those that use their profits to invest back into their businesses through increased capital expenditures. The surprise was that even as buybacks have surged in the past few years, companies that have done the most repurchases have generally performed worse than those that have increased capital spending.

A reversal appears to have happened in 2017. Before then, the stock repurchasers did better. But in 2017 and last year, the cap ex group was up 25 percent, as measured by the Nasdaq US CapEx Achievers index, compared with a rise of just 13 percent for the S&P 500 Buyback index. And only the group of capital expenditure companies performed better than the average company in the market. The S&P 500 Index was up nearly 17 percent in the same time.

It’s not clear why that shift occurred. Investors have long rewarded companies that buy back stock and have often been cautious about companies that spend a lot on capital expenditures. It’s likely because of the nature of the bets. Share buybacks are immediate and a sure thing. They reduce the number of shares and in theory make the remaining ones more valuable. Reinvesting in business is less of a sure bet. That new plant or product line or equipment might turn out to be a good investment, but perhaps not, and either way it will take time.

That doesn’t mean that capital expenditures are a worse use of cash, just less certain. Warren Buffett, for one, has argued that buybacks in certain cases can be a bad investment that hurts a stock’s value. If, for instance, a company buys its own shares for more than they are worth with its own cash, then it is wasting shareholders’ money. The overall value of the company should go down, though it doesn’t always work that way.

One reason for the reversal in performance could be volume. In the past few years, the number of companies buying back stock has perhaps grown too large. That seems most likely last year, when the companies in the S&P 500 spent $770 billion on buybacks, or about three times the $286 billion they spent in 2012. With so much being spent on buybacks, it’s a decent bet that some good money is chasing bad. In the same period, the number of companies that increased their spending on cap ex declined, raising the likelihood that a greater percentage of the remaining bets will work out, though again there’s no guarantee.

Another reason could be timing. The capital expenditure index tracks companies that have increased their spending three years in a row. Companies that started investing in their businesses in 2014 or slightly earlier may have hit the best portion of this economic cycle to capitalize on those bets. The same might not be true for companies starting to spend now.

Finally, the buyback hype machine could be winding down. Investors, after years of being told that buybacks only make stocks go up, have started to notice that the strategy of overinvesting in those companies hasn’t been paying off. And so they have been pulling their money from investments that target buybacks. The Invesco Buyback Achievers ETF, the largest exchange-traded fund that tracks stock repurchases, has dropped to $1.1 billion in assets, down from $3 billion four years ago.

But here’s the odd thing. Despite a multitude of ETFs, including ones with complicated options strategies that many think will eventually result in large losses, not a single one specializes in companies that are increasing their capital expenditures. The last one that did closed in 2017. Numerous ETFs focus on buybacks.

So this is perhaps why investors have heard so much about buybacks and why they have taken off. Wall Street explains the plain-math virtue of buybacks to companies that then have to hire brokers to do their buybacks. That creates products that will focus on those buybacks to sell to investors, pushing up those stocks in a virtuous cycle, at least for Wall Street fees, for a while.

The finance literati, including Goldman Sachs’s former CEO, Lloyd Blankfein, have recently taken to Twitter to mock plans being put forth by Bernie Sanders, Rubio and others to limit buybacks as ill-informed.

I have my doubts about those plans as well. But here’s the thing: After years of Wall Street pumping the buyback hype machine as hard as it could, investors appear to be catching on to the excess. They could use a better vehicle for backing the alternative.

To contact the author of this story: Stephen Gandel at sgandel2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Stephen Gandel is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and equity markets. He was previously a deputy digital editor for Fortune and an economics blogger at Time. He has also covered finance and the housing market.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.