Apr 17, 2021

Draghi Is Betting the House With Europe’s Biggest Stimulus Plan

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Mario Draghi is using his position as Italian prime minister to deliver the one thing he could never conjure up when he was head of the European Central Bank: massive fiscal stimulus.

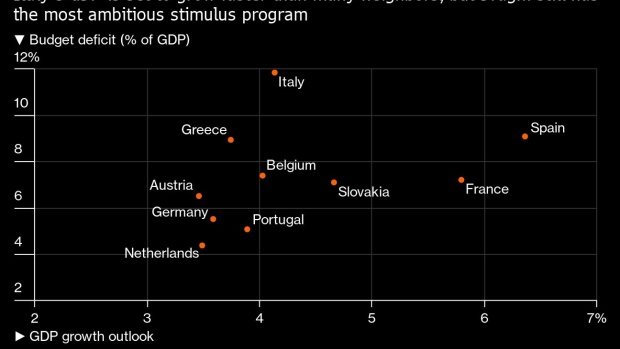

In his first few months in office he’s already on track to run through over 70 billion euros ($84 billion) in support for the economy. Combined with stimulus measures passed by the previous government, that adds up to over 170 billion euros to protect the country’s families and businesses from the pandemic. The government says that will push this year’s budget deficit to 11.8% of output the government says, making it the biggest stimulus effort in Europe.

Draghi is acting from the conviction that Europe’s economies will be stronger in the long run if fiscal and monetary authorities work together to jolt them back to health as soon as possible. While that means running up massive debts in the short run, the alternative might be a cycle of half measures and anemic expansion that would leave Italy and the European Union lagging further and further behind the U.S. and China.

“Draghi himself has said it’s a wager,” said Veronica De Romanis, professor of European Economics at Rome’s Luiss University. “But it’s the only chance we have, the alternative is austerity.”

That all-in strategy is the most audacious manifestation yet of a sea change in fiscal philosophy in Europe since the austerity-driven response to the sovereign crisis a decade ago. Draghi’s determination to make growth as the lodestar of his policy cements Italy’s place alongside France in brushing off potential constraints on spending and taking advantage of the market’s willingness to underwrite economic recovery.

Read More: France Is Driving the Campaign for Fiscal Stimulus in Europe

The extra spending will push Italian debt near to 160% of output this year, higher even than the 159.5% touched after the devastating impact of World War I. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that Italy’s economy will expand by 4.2% this year, faster than the euro-area average. But Draghi’s deficit plans are more aggressive than those of any of his European peers.

“Judged with the eyes of yesterday it would be very worrying. Today’s eyes are very different because the pandemic has made the creation of a great deal of debt legitimate,” Draghi said during a press conference in Rome on Friday. “Debt is good if you can put a company back on the market and allow it to support itself.”

Italy’s 10-year bond yields were at 0.747% on Friday after closing at a record low of 0.456% in February, while investors are still paying the French government to take their money for a decade.

With European fiscal rules suspended until 2022, the door is wide open for countries that want to provide large-scale stimulus and Italy is due to get more help when about 200 billion euros in European recovery funds starts to come through later this year.

While disputes within Poland’s governing coalition have threatened to delay the ratification of the plan, European Commission Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis said Friday that the EU is in “the final stage” of preparations for releasing the funds, although a handful of countries still have work to do. “For a vast majority of member states plans are in advanced stages,” he said at a press conference in Brussels after talks with EU finance ministers.

Draghi made a name for himself when he was head of the European Central Bank with the famous pledge to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro, signaling to markets that he was ready to push monetary policy to its limits.

The U.S. Example

Convinced that the region faced the threat of deflation, Draghi steered the ECB onto a stimulus path encompassing multiple unconventional tools from negative interest rates to quantitative easing that were previously considered unconscionable in the context of the euro zone, not least amid German dissent.

Draghi’s taboo-busting approach took its cue from the Federal Reserve in Washington but left the euro area riven by disagreements by the time he left the ECB in late 2019. He had pushed through his final round of bond purchases over the public opposition of central bankers from Germany, France and the Netherlands, leaving scars that his successor, Christine Lagarde, is still tending to.

While he was driving the monetary policy engine at the ECB, Draghi at times voiced his frustration that governments weren’t doing more with fiscal policy to support demand.

Now that he has control of the fiscal levers in the EU’s third-biggest economy, he’s helping to drive the bloc more into line with a push across the advanced world to prioritize extraordinary stimulus as the central response by governments to an exceptional economic crisis. In the U.S., that approach has been reinvigorated this year with direct payments to citizens authorized since the onset of President Joe Biden’s administration.

As he presented his plans for another round of borrowing on Friday, one reporter asked him if he didn’t feel that another 40 billion euros was going too far. The prime minister’s answer suggested having embraced his fiscal gamble, he’s going all in.

“I don’t think if, instead of being 40, it had been 30 you would not have had the shivers,” he said. And then he added, “Growth is the key criterion: it must be sustainable growth.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.