Dec 3, 2019

ECB Sub-Zero Rate Policy Faces Pushback From Finance Ministers

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Explore what’s moving the global economy in the new season of the Stephanomics podcast. Subscribe via Apple Podcast, Spotify or Pocket Cast.

European Central Bank officials face increasing pushback against their negative interest-rate policy in private engagements with the region’s finance ministers, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

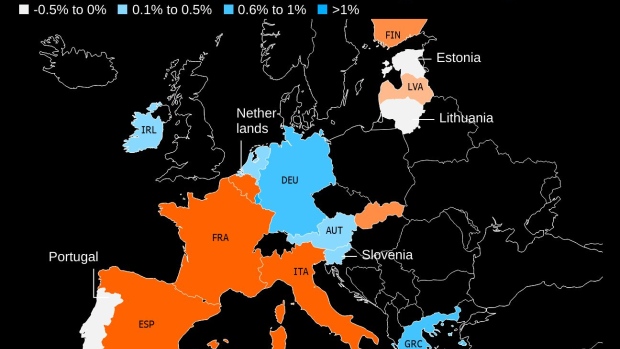

Some euro-zone finance chiefs, particularly from northern Europe, are challenging the ECB’s sub-zero monetary stance during confidential discussions on the economy, complaining about its detrimental impact on savings and pension systems, said the people, who declined to be identified because of the sensitivity of the matter. The ECB says negative rates wouldn’t last so long if governments did more to stimulate economies.

The tensions behind closed doors may mirror disagreements between central bankers, highlighting the challenges faced by newly installed ECB President Christine Lagarde as she navigates a policy path already beset by a legacy of controversy. Ministers’ concerns may be formally irrelevant because her institution is independent to ensure freedom from influence, but it derives its legitimacy from political consensus -- and its actions directly affect voters.

Lagarde will attend a gathering of euro-zone finance ministers in Brussels this week, though the discussion will focus on finalizing contentious overhauls to shore up the euro area, including a reform of its bailout fund and a push for common deposit insurance.

One prior instance of discord took place in the immediate aftermath of the ECB’s decision to cut its deposit rate to minus 0.5% on Sept. 12. At a meeting of the Eurogroup ministers the next day, both Belgium and Luxembourg complained about risks posed to asset prices by ultra-low monetary policy, a person with knowledge of the matter said.

At another Eurogroup meeting on Oct. 9, the Netherlands also raised the matter of negative interest rates and “possible risks for savers and financial stability,” according to a report by Dutch Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra for his country’s Parliament.

Such sentiments may reflect the controversy of the September decision -- both Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann and Dutch central bank chief Klaas Knot opposed the broad stimulus package, especially the resumption of quantitative easing -- and also frustration among voters at the lack of interest earned on savings.

Hoekstra warned in September that the ECB rate cut would have “huge consequences” in the Netherlands. In Germany, the head of Bavaria’s regional administration called on the government to prohibit banks from passing on negative rates to savers, or else to help deduct the cost from tax bills. A convention of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s ruling CDU party discussed seeking a change in monetary policy to protect retirement savings.

Financial institutions are also loudly complaining. Last month, Deutsche Bank AG President Karl von Rohr described low rates as “the biggest challenge facing the European financial industry.”

The ECB’s response, both in public and in private, has been to shift the responsibility to governments. That can be seen in Draghi’s repeated emphasis toward the end of his term on the need for fiscal stimulus by countries with the space to do so, to complement easing and thereby accelerate the prospect of a return to more normal policy.

“If governments want to see a faster exit from unconventional policies, it is in their interests to align with monetary policy,” he said in Athens just days before the Oct. 9 Eurogroup meeting, in one such example. “But this is not what we have seen.”

Some governments take the ECB’s side. At the Sept. 13 Eurogroup, French and Italian ministers spoke out to share the central bank’s assessment that national budget policies should complement its monetary easing, the same person said. The main candidates to do that are those with fiscal space such as Germany and Netherlands, neither of whom are rushing to respond.

In the meantime, alternatives such as a change to the EU’s deficit rule to allow for more leeway by other countries, or a common fiscal stimulus program, have no majority support among finance ministers, according to another official.

--With assistance from John Hermse and Zoe Schneeweiss.

To contact the reporters on this story: Birgit Jennen in Berlin at bjennen1@bloomberg.net;Viktoria Dendrinou in Brussels at vdendrinou@bloomberg.net;Patrick Donahue in Berlin at pdonahue1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Ben Sills at bsills@bloomberg.net, Craig Stirling

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.