Jan 16, 2020

EnLink’s Dividend Cut Doesn’t Go Nearly Far Enough

, Bloomberg News

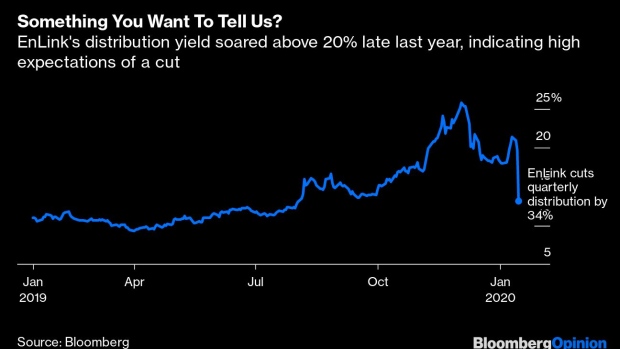

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The language around a dividend cut is necessarily delicate. Hence, EnLink Midstream LLC characterizes the 34% drop investors are about to experience as a “resetting.” The problem is EnLink has taken the delicacy thing a bit too far — and thereby garbled the message.

To say this distribution cut was expected would be something of an understatement.

EnLink’s problem is a familiar one among pipeline operators. Growth across much of its business has slowed, bringing high leverage and calls on its cash flow into sharp focus. New guidance suggests Ebitda will creep up a little in 2020. The old distribution would have taken half of that; interest and payments on preferreds roughly another third. That wouldn’t leave much for capital expenditure or cutting debt, which stood at 4.2 times adjusted Ebitda at the end of September (more if you layer on the preferreds).

The new distribution saves just shy of $190 million a year, enabling EnLink to generate $10-$70 million of free cash flow after capex and distributions in 2020, according to the company’s own guidance. Here is where, despite EnLink having done the right thing in resetting dividends, it took its delicacy a bit too far.

EnLink’s sky-high dividend yield was a signal it was distressed. The way to cure distress is to cut leverage. Even at the high end of guidance, $70 million merely scratches the surface, equivalent to less than 2% of debt outstanding at the end of September. EnLink’s own guidance suggests leverage will barely drop (and may even rise a little) this year.

It is clear that, rather than diverting as much cash as possible to paying off debt, EnLink hopes to ultimately grow its way to lower leverage. On its call Thursday morning, management emphasized the first call on excess cash flow would be investing in new projects. This is why, oddly and as laid out toward the back of the latest slide deck, EnLink’s guidance is for free cash flow to actually drop in the high case for Ebitda versus the low case.

The messaging here is upside down. Promises of growth, once a strong currency in energy circles, have been debased over the past five years. EnLink’s own guidance for “modest” growth in Ebitda actually encompasses $75 million of promised cost savings, which tells you how much pressure is bearing down on the underlying business.

There’s a lot of history to learn from here. Back in late 2015, Kinder Morgan Inc. slashed its dividend by roughly three quarters to deal with its debt, presaging the great resetting that was to come across the midstream sector. Even then, though, Kinder tried to soften the blow by maintaining a robust capex budget centered on growing its way out from under — a budget it had to slash twice in a matter of months as it became clear that wouldn’t fly. Similarly, Plains All American Pipeline LP’s “one and done” convertible issue in early 2016 segued into what one might have called a “two and through” distribution cut — except that another, even bigger cut followed a year later. Both stocks have been dead money for much of the past four years.

EnLink could have used this as an opportunity to rip off the band-aid. As it is, the 34% cut leaves the stock yielding about 13%, still at the high end in a troubled sector and looking more stressed than generous. A 65% cut would have taken that yield down to a still-robust 7% and, using the company’s own guidance, resulted in almost $220 million of free cash flow.

The problem, of course, is the elephant not quite in the room called the Global Infrastructure Partners term loan. GIP took on a $1 billion loan when it bought 46% of EnLink. That stake is now worth only about $1.2 billion, not much more than the loan balance, which stood at “less than $900 million,” according to an EnLink presentation in late November.

It is also serviced by distributions from EnLink (see this column from a couple of months ago for details). And this is perhaps the biggest problem with EnLink’s delicate touch. One of the questions that has dogged EnLink is whether GIP’s loan-servicing needs would trump the imperative of fixing the balance sheet. By my math, assuming a loan balance of just under $900 million, GIP needs a minimum annual payout of roughly $75 million. A 65% cut to EnLink’s distributions, while offering faster direct deleveraging, would have cut GIP’s distribution to less than $90 million — not much more than the bare minimum. At 34%, it gets $168 million.

In taking the path of a smaller cut and emphasizing growth, EnLink’s strategy looks more closely aligned with its big, private-equity shareholder than the zeitgeist in the public market. Its own guidance indicates a listless 2020 for the stock, with distributions lower but leverage staying flat. Rewards are backdated to 2021 and beyond. As messages go, that sounds so 2015.

To contact the author of this story: Liam Denning at ldenning1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.