Nov 10, 2022

Errant Remark on China Rescuing El Salvador Shows Pressure on Xi

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Investors were momentarily puzzled this week when El Salvador Vice President Felix Ulloa said China had “offered to buy” the nation’s distressed bonds. Anything close to that by a leading sovereign creditor hasn’t happened since the late 1980s, when the US moved to bail out Latin America.

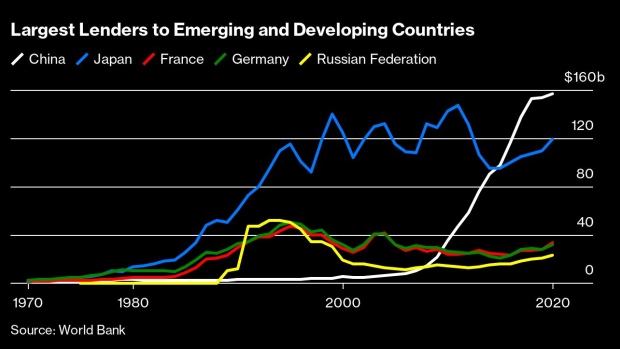

Leaders in the Central American nation quickly walked back the comments, with Ulloa saying he was taken out of context. A spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry on Tuesday denied awareness of such a plan. Either way, the errant remark put a spotlight on a much wider dilemma for Chinese leader Xi Jinping: As the world’s largest creditor nation to the developing world, how much debt relief should Beijing provide?

Over the past decade, China has financed roughly $1 trillion in infrastructure spending around the globe as part of Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative. But spiraling inflation, rising energy prices and increased borrowing costs mean Beijing is now facing the prospect of large-scale defaults for the first time.

About 60% of China’s overseas lending is to countries that are in debt distress, according to a report earlier this year published by the Europe-based Centre for Economic Policy Research. Borrowers like Sri Lanka and Zambia are already engaged in restructuring their debt, and others may follow in what could become a cascade of defaults.

China’s role as the primary lender for many developing nations has increasingly become part of the wider strategic competition with the US for influence across the globe. President Joe Biden, who is set to meet Xi at the Group of 20 summit in Indonesia next week, has pushed an alternative financing program to China’s plan backed by US allies.

The US has repeatedly denigrated China’s lending model as a so-called debt trap, a practice where creditors ultimately seek to take control of key assets, and has sought to rally nations to reject Beijing’s cash or seek better terms. In September, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken urged Pakistan to press China for debt relief after a third of the country was submerged by floods.

Beijing has emphatically rejected US assertions about its lending, snapping back at Blinken for “unwarranted criticism.” Still, China has recently become much more cautious with its overseas financing as Xi’s Covid Zero policy keeps the nation isolated and hurts an economy now expanding at close to the slowest rate in four decades.

China largely stood by earlier this year as Sri Lanka defaulted on sovereign debt for the first times in its history, and also hesitated in rolling over debt to Pakistan -- one of the most important Belt and Road nations. Instead, Beijing has looked to multilateral institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the Paris Club of rich creditor nations to help resolve debt issues, though there are signs it’s stepping up engagement.

An agreement reached with Zambia earlier this year offers a potential template for China to use for countries like Pakistan that are looking to renegotiate debt. The committee of bilateral creditors, co-chaired by China and France, provided financing assurances to unlock a $1.3 billion IMF deal -- though it’s not clear what level of losses they’ll tolerate under a restructuring.

Offering debt support suggests China’s awareness and desire to reframe their aid contributions in a more positive light, particularly as most of this is still provided in the form of loans where a return on investment is expected, said Raffaello Pantucci, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

“The trend signals China is trying to think more laterally about what aid actually means and to be more munificent,” Pantucci said.

A 2021 study co-published by institutions including AidData at William & Mary of 100 debt contracts signed between Chinese lenders and government borrowers across 24 different countries showed unusual confidentiality requirements, an attempt to seek advantages over other creditors and clauses that would potentially allow lenders to influence the domestic and foreign policies of borrowers.

Rather than “debt-trap diplomacy,” China is looking to make money from projects while obtaining strategic access to commodities, foodstuffs, markets and technology, said Evan Ellis, professor of Latin American studies at the US Army War College Strategic Studies Institute.

A key goal for Beijing was “ensuring that those deepening commercial webs also bear strategic fruit, from partner silence on issues such as Taiwan, Xinjiang or Hong Kong, or future access to strategic facilities,” Ellis said.

When El Salvador recognized Beijing in 2018 and severed ties with the self-governed island of Taiwan, Xi’s government provided the country with 3,000 tons of rice and promised about $150 million toward infrastructure projects.

While it wouldn’t be surprising that China would provide some relief to El Salvador, it’s rare for creditor nations to step in and directly buy distressed bonds. The last major effort was in the late 1980s and ’90s, when the US intervened to help manage the fallout of a credit crisis across Latin America after it led a wave of lending to the region.

Any similar deal would be “highly unlikely,” said Matthew Mingey at Rhodium Group. “It’s unclear that China would view El Salvador as geostrategically significant enough to justify lending into a clearly risky situation.”

Both countries hope two-way trade negotiations will start soon after the Latin American country ended its free-trade agreement with Taiwan, a spokesperson for China’s Commerce Ministry said in a Thursday statement.

China also faces its own domestic hurdles in taking on a more proactive role in debt relief. While the financial institutions in China that facilitate the lending must answer to Xi, they have numerous ways to resist political efforts that may threaten to undermine their balance sheet, according to Yufan Huang, a researcher at Cornell University who focuses on China-Africa ties.

“It is the first time for many of the Chinese bankers to deal with a major overseas debt crisis,” he said. “I believe they are still processing the pain and pondering what to do.”

--With assistance from Alonso Soto, Sydney Maki and Matthew Hill.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.