Nov 23, 2022

ESG Fight Injects Fresh Risks Into Public Pension Portfolios

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- When Florida Governor Ron DeSantis emerged as one of the most vocal critics of so-called woke money managers, he thrust the state’s pension funds into a red-hot debate.

On one side are Republicans, who say ESG investment strategies leave returns on the table for the sake of political correctness. On the other are Democrats who argue failing to account for climate change will exact steep financial costs in the long term.

Both say they’re upholding their fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of clients. Making investment decisions based on anything other than performance would violate that obligation. But some research has found that politically motivated investment decisions can hurt long-term performance, costing some state pension funds billions of dollars as they’re struggling to keep the promises made to retirees.

Republicans in Missouri, Louisiana and South Carolina pledged to pull a combined $1.5 billion of public pension and state treasury funding from BlackRock Inc. after the world’s biggest asset manager became a prominent backer of ESG investing strategies. Meanwhile, those in more liberal states, including New York and Minnesota, proposed divesting from the fossil-fuel industry.

The current debate is reminiscent of the 1990s and early 2000s, when several retirement systems voted to divest from so-called sin stocks such as tobacco or weapons manufacturers. States including Massachusetts, Maryland and Florida purged tobacco investments from their pension funds.

A 2001 tobacco industry divestment ultimately cost the California Public Employees’ Retirement System $3.69 billion over almost two decades, according to a report last year by Wilshire Associates.

In October 2020, the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College reported an analysis of 176 pension funds, roughly two-thirds of which had “a social investing state mandate or an ESG policy in place.” Plans with state mandates had them for an average of 10 years and saw a decrease in returns of almost 2 basis points a year.

“Just to go down 20 basis points, that costs the state of Florida about $400 million each time just as an ongoing annual budget item,” said Leonard Gilroy, senior managing director of the Pension Integrity Project at the Reason Foundation, a libertarian think-tank.

Chris Ailman, chief investment officer of the California State Employees’ Retirement System, told Bloomberg this year that Calstrs has divested six times in two decades -- for purely financial reasons -- and the moves cost the pension fund money, without moving the needle on social issues.

Read more: Calstrs Says Dumping Oil Stocks Risks a Polluter ‘Rebellion’

Jean-Pierre Aubrey, the lead author of the Boston College study, sees risk in both the pro-ESG and anti-ESG camps.

They’re “two sides of the same coin,” he said in an interview. “When you start meddling in pensions for any other reason than getting returns, the outcome is gonna be pretty clear -- and again, it’s hard to really affect anything through just not holding someone’s stock.”

Florida’s State Board of Administration, which oversees the state pension fund and other investments, adopted a resolution in August reiterating a commitment to its fiduciary duty and, notably, didn’t include language that would require it to liquidate any of its current holdings.

DeSantis’s office referred questions to the SBA, which said in an emailed statement that neither it nor its managers “use ESG ratings as a way to screen or limit an available investment opportunity set.”

In oil-rich Texas, meanwhile, a law that took effect last year is designed to limit state business with companies that restrict investment in the fossil-fuel industry. The state will have paid $303 million to $532 million in additional interest in the first eight months following enactment, according to a study by the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business.

Those increased costs are the result of five large municipal bond underwriters leaving the state after being banned from working with certain banks, the study found.

Read more: BlackRock Tells Texas It Supports Investments in Oil and Gas

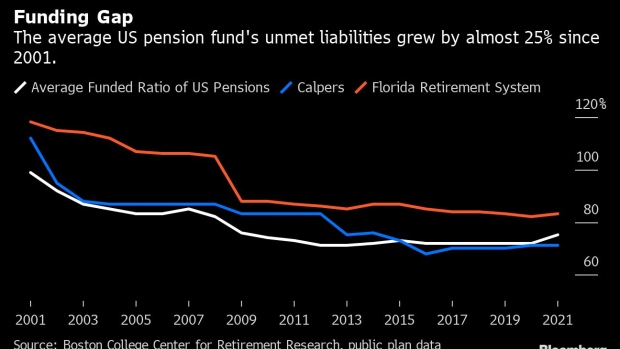

Like most public pension funds in the US, Florida’s is facing a funding shortfall, meaning state taxpayers and the public schools system -- whose employees make up 48% of the state’s pensioners -- are increasingly burdened with filling the gap. Florida is 83% funded -- above the national average, but still $35.6 billion short of what it needs to meet its long-term obligations to 2.6 million beneficiaries.

Calpers, the nation’s biggest public pension plan, said this year that it has just 71% of the necessary funding.

The 2008 financial crisis forced a reckoning for most public pension plans. Florida slashed costs, scrapping cost of living adjustments to future benefits, and imposed an annual employee contribution to help pay down its pension needs, which had been amplified by years of underreported losses.

For decades, the state’s retirement system assumed annual returns would surpass at least 7%, but they exceeded that threshold in just 10 of the past 20 years. Since 2017, Florida incrementally dropped its assumed rate of return to 6.8%, helping to lower the pension fund’s long-term debt.

--With assistance from Annie Massa and Saijel Kishan.

(Updates to add QuickTake video)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.