Nov 4, 2018

EU Faces a Risk in 2019 That Has Nothing to Do With Populists

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Anti-establishment forces are attracting plenty of attention as they prepare a fresh assault on the European Union next year, but the bloc’s legislative elections may also highlight a more insidious threat: voter apathy.

Turnout at European Parliament elections has fallen steadily since the first direct ballot took place four decades ago, going from almost 62 percent in 1979 to less than 43 percent in 2014.

The assembly, whose two biggest parties are the pro-EU Christian Democrats and Socialists, is mounting an unprecedented get-out-to-vote campaign in a bid to reverse the trend on May 23-26.

The goal is also to counter the kind of energetic, targeted rallying deployed by populist parties, which have gained ground in member states from Italy to Poland. Steve Bannon, an architect of Donald Trump’s U.S. presidential-election win, has set up an organization in Europe to support parties running against further integration in the continent.

“It boils down to whether Europe is regarded as useful or not,” Ramon Luis Valcarcel, a Spanish Christian Democratic vice president of the EU Parliament who oversees its information policy, said in an interview at the assembly’s headquarters in Strasbourg, France. “While anti-Europeans -- populist and nationalist movements -- make up about a quarter of the electorate, pro-Europeans are reacting and showing more interest.”

Voter indifference in European legislative elections to date has posed few dangers for the EU because mainstream parties have remained firmly in the driver’s seat, with the main impact of falling turnout being merely to dent the pride of committed federalists.

Since the last ballot, however, the dynamics have changed as a result of the U.K.’s vote to leave the EU, the rise to power of overtly populist governments in Italy and Poland and the challenge to mainstream parties in such core countries as Germany.

Bannon is creating a loose alliance of populist forces across Europe -- dubbed The Movement -- and will offer parties polling, data analytics and messaging. And while the former Trump aide thinks it’s doubtful nationalist parties will gain a majority in the EU Parliament in May, they’d like to gain at least a third of the seats to be able to disrupt the assembly’s business through “command by negation,” he said.

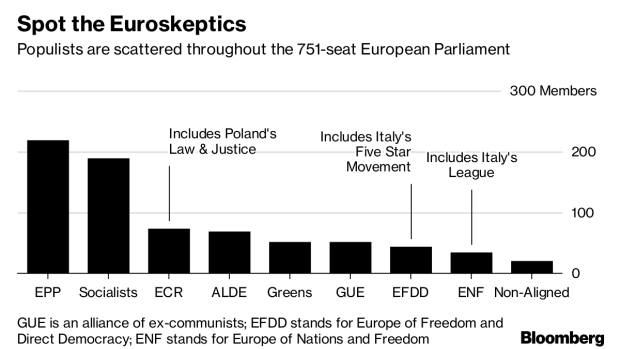

There is an irony in the growing apathy toward EU Parliament elections: The trend has coincided with a steady expansion of the assembly’s powers, which touch on legislative issues ranging from banker bonuses to car emissions and political matters including appointments to top European jobs. Consequently, a wide range of EU business could be jeopardized by further big gains for euroskeptics, who hold close to 200 of the Parliament’s 751 seats.

“In the current part of the campaign, we are talking about the achievements of the EU such as the defense of fundamental values, the display of solidarity among member countries, environmental protection and measures taken to increase investment and jobs,” Valcarcel said in the interview in his Strasbourg office. “That way, citizens will realize that Europe is important.”

In a grass-roots initiative that is the first of its kind, the EU Parliament is mobilizing people to vote and to persuade others to do so. Through a web portal called “This Time I’m Voting,” so far more than 76,000 people have pledged to cast ballots and more than 4,000 have volunteered to help spread awareness of the elections.

This campaign pillar, called the “ground game,” will also make use of the assembly’s offices in EU capitals and target citizens categorized as “weak abstainers” who are inclined to vote but who risk not doing so on the day without encouragement. A priority in all this is to mobilize young people because they are regarded as an instinctively pro-EU segment.

The EU Parliament has also created a unit to counter “fake news,” responding to evidence that in 2016 the U.K. referendum decision to leave the bloc and even Trump’s victory were affected by falsehoods.

“Brexit is a consequence of fake news,” Valcarcel said.

Marjory van den Broeke, who heads the new unit, pointed a finger at forces abroad interested in weakening the EU.

“Part of this disinformation is pushed by foreign countries, feeding on unjustified but persistent bias against the EU,” she said. “We hope to show that this is what it is, unwarranted bias.”

In a further groundbreaking step, the EU Parliament is working with the European Commission, the bloc’s executive arm, to examine ways to counter common misconceptions about the EU.

Not least among these is the view that the bloc is primarily a self-serving, costly bureaucracy that, when it affects the everyday lives of ordinary people, does so by subjecting them to intrusive rules.

Can this strategy, which also includes an “air game” focused on ensuring proper election coverage by television broadcasters, end the 35-year decline in voter participation in the European legislative ballot?

“I believe turnout will be higher than in 2014, but I wouldn’t want to venture a precise prediction,” Valcarcel said. “It will depend on a lot of things.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Jonathan Stearns in Strasbourg, France at jstearns2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alan Crawford at acrawford6@bloomberg.net, Richard Bravo, Nikos Chrysoloras

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.