Nov 22, 2022

EU Labor Supplier Romania Turns to Asia to Cover Its Own Gaps

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- No country in the European Union has watched its workforce shrink more than Romania, but thanks to a gradually growing economy -- and an injection of billions of euros from the bloc -- that’s changing.

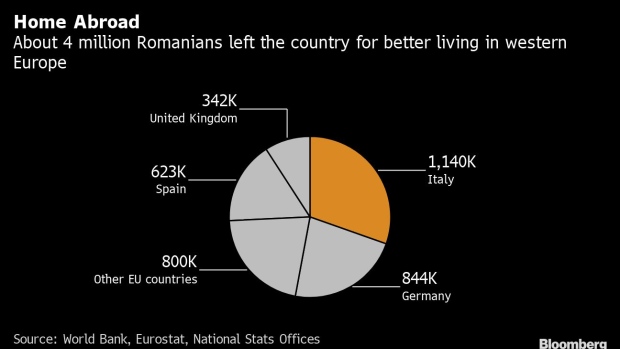

Since joining the EU in 2007, the Black Sea nation’s population has fallen by more than 11% to 19.3 million. Low-skilled workers led the exodus from what was once one of the EU’s poorest countries to better-paying jobs in richer member states.

Now, however, Romania is due to receive more than 80 billion euros ($83 billion) from the EU’s pandemic recovery program and budget allocation, with about a third earmarked for infrastructure in the coming five years. Because of the magnitude of the work, officials are seeking to boost the workforce by as much as 10% by luring about half a million laborers from Asian countries such as Bangladesh and Nepal.

“The risk of losing the money is very, very big,” said Cristian Erbasu, who chairs an association of construction companies FPSC and his own firm Constructii Erbasu SA. “We’ll need a few hundred thousand extra workers.”

The labor shortage underscores a trend that has washed over most of the EU’s poorer eastern wing. With the right to live and work in any country of the world’s biggest passport-free trading area, millions of people have left.

That’s led to both a brain drain -- and record-low unemployment. It’s also opened opportunities for arrivals from less well-off countries outside the EU to take jobs usually filled by people who are now working in the likes of Germany and Italy.

In many former communist countries, those gaps are largely being filled -- at least temporarily -- by people fleeing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, where the destruction wrought by President Vladimir Putin’s military has driven millions from their homes and forced millions more out of the country.

In Poland, more than 370,000 Ukrainians have been hired since the war started, according to Labor Minister Marlena Malag. Next door, Czech companies have hired 100,000 Ukrainians. But Romania has benefited less. With its language a barrier -- Romanian is related to Latin and isn’t Slavic -- it’s only seen a few thousand Ukrainians stay.

Instead it’s turned to workers like Santi, a 24-year-old from Nepal. He arrived in Bucharest last year on a three-year contract and now makes 750 euros a month insulating buildings across the Romanian capital, enough to also support his parents and two younger sisters at home.

“I send at least 300 euros home every month,” Santi, who goes only by one name, said in a downtown park. “I like it in Romania -- I’ll try to extend my contract for at least three more years.”

The influx of workers from less developed countries also underscores another economic trend: Romania’s convergence with richer EU countries.

The 27-member bloc’s second-poorest state when it joined 15 years ago, Romania passed Latvia, Slovakia and Greece last year with an output per capita, adjusted for purchasing power, of 73% of the EU average, an increase of almost half. The average net wage has quadrupled over that time to 900 euros a month.

While significant, those improvements are still insufficient to keep workers at home. As many as 100,000 still leave each year, according to Eurostat. Persistent poverty in rural areas doesn’t help, former central bank board member Daniel Daianu said.

“We still have large discrepancies among regions and living conditions haven’t improved everywhere to the extent to convince people to stop leaving or to come back,” he said. “A big part of that workforce won’t return.”

With unemployment currently at 5.2% -- not far off a record low -- the need for skilled workers has pushed wages higher. The gaps are the largest in services, hospitality, agriculture and construction, the Labor Ministry said in a response to Bloomberg questions.

“We’re seeing some huge wages in the construction sector,” said Lucian Azoitei, the chief executive officer of developer Forty Management, who’s waiting for permits for a 110-million euro real-estate project in Bucharest. “We had a very good site manager who we used to pay 6,000-8,000 euros per month, and he still left abroad for even more money.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.