Dec 5, 2022

EU Zeros In on the Balkans as Its Popularity There Starts to Ebb

, Bloomberg News

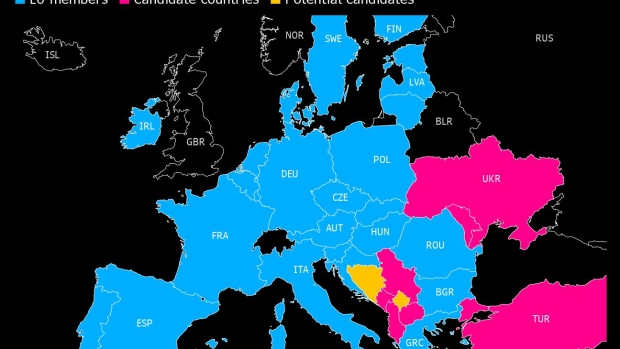

(Bloomberg) -- For decades, joining the European Union was seen as the holy grail for the countries of the Western Balkans. But for most of them, that dream remains elusive, and they’re starting to look for alternatives.

People in Albania, Serbia, North Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro have all become more vocal in their disillusionment this year as Europe grapples with the aftermath of Russia’s war in Ukraine and a cost-of-living crisis.

“The polls in the past 18 months, both in our country and the region, show a decline in support for the EU,” North Macedonia’s president, Stevo Pendarovski, said last week. Brussels is mainly to blame, he said, as “we objectively don’t see the euro-integration process moving forward.”

The EU has taken notice. It’s holding a summit on Tuesday with the leaders of its 27 members in Albania’s capital, Tirana, to show it still believes the Balkan states will one day join the fold.

It’s the first such official meeting to take place in the region, and the choice is notable -- Albania has been among the most vocal proponents of EU membership.

“It’s the first time in our history that we can choose,” Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama said in an Interview on Monday. “And for us, Europe is very much the same as it was for them who founded it, a place of refuge from war, from dictatorships, from conflicts, a place of peace and security.”

Complaints about delayed integration haven’t only come from countries where hope of joining the EU remains strong. Even the European Parliament rebuked the bloc’s leaders for “not delivering on the EU’s long-standing promises.”

“The EU’s lack of engagement and credibility over the past few years has created a vacuum, thereby opening up space for Russia, China, and other malign third actors,” it said.

Being left out means being left behind economically. The six Balkan countries that haven’t won membership all had living standards below 50% of the bloc’s average last year, while the 12 former communist states that have joined since 2004 exceeded that level.

Take North Macedonia, which along with Albania started accession talks in July after waiting for 17 years to do so after a tumultuous process in which it even changed its name to qualify.

Having cleared that hurdle, its progress has still stalled due to a spat with neighbor Bulgaria, which is asking for a change in North Macedonia’s constitution before it can proceed with the membership process.

That’s been hard to swallow for people in North Macedonia, as the delay may add more years to their chances of a richer life that would more resemble EU standards.

“There are many countries that believe the process should be faster,” U.S. Special envoy for the Balkans Gabriel Escobar said last week.

In Tirana, EU leaders will stress the importance of aligning the bloc’s position on sanctions against Russia with Western Balkan countries, according to an EU official familiar with the matter. Vucic, who has sought to retain close ties with Russia, has repeatedly refused to join the sanctions.

But, while also in limbo regarding the EU, Serbia has lent a hand, trying to increase its influence in a region that it once dominated from Belgrade before the bloody breakup of Yugoslavia.

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic, who’s juggling close ties with Russia and a desire to join the EU, was first to send Covid-19 vaccines to North Macedonia two years ago.

And his government changed laws in October so it could start exporting natural gas to its southern neighbor.

Vucic is also pushing to strengthen the Open Balkans forum, which facilitates trade and travel and eases telephone roaming charges. He argues that, without a clear EU membership target date, the Balkan states should strengthen economic ties.

The EU has slammed the initiative, along with officials from several Balkan nations that have shied away from it. They’re concerned that countries that fought wars to become independent from each other in the 1990s may lose focus on accession.

But ultimately, it’s the EU that should bear the brunt of the blame for a lack of progress toward membership, according to Skopje-based political analyst Ljupco Popovski.

“In the absence of a big reward, people have sought to look for some immediate benefits, even if they were smaller,” he said.

--With assistance from Misha Savic, Andrea Dudik, Rosalind Mathieson and Irina Vilcu.

(Updates with comment from Albanian prime minister in sixth paragraph, sanctions against in 14th.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.