May 4, 2022

Europe Confronts Difficult Path in Making a Russian Oil Ban Work

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The European Union’s move to ban Russian crude this year will cause major headaches but it should just about be workable if some countries are shown leniency.

There’s still opposition within the bloc. Hungary has previously said it would veto a ban and Slovakia will demand an exemption, even though the two countries will be given an additional year to to comply. Both rely on crude delivered through the Druzhba pipeline from Siberia to run their refineries. But Germany, which had long argued against the move, is now ready to support it.

Seaborne flows of Russian crude to some parts of the EU are already falling in response to self-sanctioning by refiners and traders, but the actions of buyers vary greatly. Russia’s closest neighbors in the Baltic -- Finland, Lithuaniua, Poland and Sweden -- have have already reduced their purchases of Russian seaborne crude to near zero from about 500,000 barrels a day before Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. In contrast, shipments to Mediterranean countries have soared, partly as a result of increased deliveries to Russian-owned refineries in the region.

Alternative Supplies

Europe is sourcing more from elsewhere. That’s both in response to the war but also, in the case of Poland, part of a longer-term strategy of reducing dependency on Russia. The volume of Middle Eastern oil being shipped to northwest Europe from Sidi Kerir on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast has soared since the start of the year after Polish refiner PKN Orlen SA signed a long-term supply deal with Saudi Arabia in January.

Europe is also pulling record amounts of crude from the U.S. with almost half of all exports from the Gulf coast heading to Europe last month. Rising production and the release of crude from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve have helped boost U.S. shipments, throwing a lifeline to European refiners.

More crude may also come from the Middle East. Iraq, OPEC’s second-biggest producer, is considering shipping more oil to Europe, according to Alaa Al-Yasiri, director general of the state-run marketing oil company known as SOMO.

But don’t expect producers to crank open the taps to offset any reduction in Russian supplies. The OPEC+ group of producers, which includes most of the Middle Eastern heavyweights alongside Russia, is expected to stick to its plan of modest monthly output increases, and is struggling even to keep pace with that.

Mediterranean Challenge

The picture is more challenging in the Mediterranean region than in northwest Europe, where importers are still relying heavily on Russia, than it is in northwest Europe.

Shipments to Italian ports have soared in recent weeks, largely due to a surge in the volume moved by Russia’s Lukoil PJSC from the Baltic Sea to its refinery on the Italian island of Sicily. Italy may need to follow Germany’s lead in tackling the issue of a Russian company owning refining assets, as the government in Berlin is doing with Rosneft PJSC’s ownership of the Schwedt refinery.

What’s happening to flows of Russian crude through the giant Druzhba pipeline network is less transparent. And it is no surprise that the EU’s two most vocal critics of sanctions rely on the route to feed their refineries.

But even here, EU countries are looking at alternatives to supplies from Russia. Druzhba, which translates as ‘friendship’, is often referred to as a Russian pipeline, but that’s not entirely true. Sections in European countries are locally owned and operated, so parts would almost certainly be used to transport non-Russian barrels were a ban to be enacted. That may be easier along the route’s northern branch than in the south.

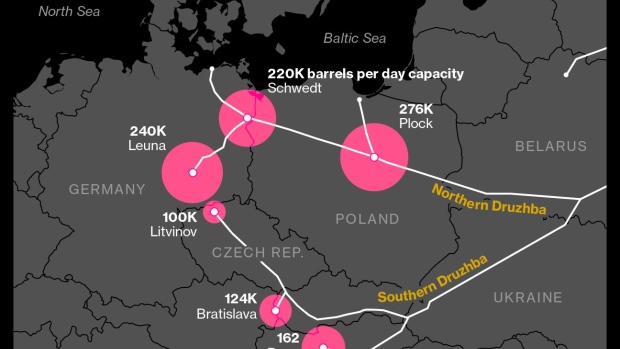

In eastern Germany, the Schwedt and Leuna refineries historically depend on Russian crude delivered through Druzhba, but that appears to be starting to change.

Economy Minister Robert Habeck said Germany has already cut its reliance on Russian oil to about 12%, from 35% before the invasion of Ukraine, enough to make a full embargo “manageable.” The Leuna refinery has already found alternative suppliers, Habeck said, and flows to the two plants will be topped up from stockpiles held in the western part of Germany. That’s only a temporary solution.

Polish Pact

Germany and Poland are finalizing a deal to allow spare capacity in the Polish pipeline system to be used to carry crude from the port of Gdansk to the refineries in eastern Germany. That route would utilize the Pomeranian pipeline from the coast to storage tanks at Plock, and then the western section of the Druzba line from there to Germany.

But ending Poland’s own purchases of Russian crude will limit the capacity of that route to deliver supplies further west, with the key bottleneck likely to be at the port of Gdansk, which also handles deliveries for the local refinery.

In other words, it still looks challenging to get the right amount of crude to eastern Germany without depleting inventories.

If Germany has gone a long way to solving its crude-diversification conundrum, that leaves refineries in Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic as the ones most at risk from a loss of Russian supplies. Plants in all three countries depend on deliveries through Druzhba. As in Germany’s case, Russian crude could be replaced with supplies from elsewhere, but alternatives are likely to be more expensive and logistically difficult to receive.

Reality Test

Hungarian oil refiner MOL Group said in February that it has sufficient pipeline capacities to supply its landlocked refineries -- the Duna refinery in Hungary and Bratislava in Slovakia -- through the Adriatic pipeline. That route can be used to transport potentially non-Russian supplies delivered to the Croatian port of Omisalj to the refineries using the local sections of Druzhba.

The Czech Republic, whose Litvinov refinery lies at the end of the southern branch of the Druzhba pipeline, has taken the opposite stance to its eastern neighbors. Foreign Minister Jan Lipavsky told reporters in April that the country wants the EU to halt Russian oil imports during its presidency of the bloc in the second half of 2022.

Litvinov can receive non-Russian crude through existing pipeline networks. The Trans-Alpine and IKL pipelines allow supplies to be piped from the Italian port of Trieste all the way to Litvinov, utilizing the western end of Druzhba’s southern branch.

So, in theory at least, Europe stands a chance of being able to work around any loss of Russian crude. The reality might be something else. The bloc’s refineries will be competing for the right types of oil for their needs in an international market place. The solutions also appear to rely on a global logistics network running like clockwork.

More Tankers

Even if refiners’ needs can be met, it will come at the expense of efficiency and that’s going to raise coasts and stretch supply chains. More Russian crude will be sent from ports in the west of the country to refineries in Asia, heading off on voyages four times as long as traditional routes to northwest Europe.

Meanwhile, European refiners will need to rely more heavily on crude shipped across the Atlantic or through the Suez Canal as supplies form nearby Russian ports are slashed. That’s going to boost demand for tankers, with vessels tied up for four times as long as before on each shipment. Not only will delivery costs rise in line with longer voyages, but the underlying shipping costs are set to increase too, pushed higher by rising demand.

We face the prospect of tankers carrying Russian crude diverted from Europe to Asia passing vessels carrying Middle Eastern crude diverted from Asia to Europe in the Suez Canal.

Diesel

Crude is far from the only problem, and not even the biggest one.

That accolade almost certainly goes to diesel that’s needed to power industry and transport. The 27 EU countries imported about 18 million tons of Russian diesel in 2020, according to Eurostat, and that’s likely to have risen last year amid the recovery from the Covid pandemic. Russian supplies accounted for more than 40% of the fuel imported from outside the bloc.

As with crude, European countries are turning to supplies from elsewhere. Flows of the transport fuel from the Persian Gulf to Europe were set to rise almost 130% in April to 379,000 barrels a day, according to lists of charters and tanker tracking data compiled by Bloomberg. That’s the highest figure since October 2020 and bigger than the 166,000 barrel-a-day slump in European imports from Russia, according to the bookings data, which is still provisional.

Although alternative diesel supplies will face similar cost pressures to crude, logistics ought to be easier, as product is already delivered by ship to European ports. That avoids the problem some crude importers face of having to replace pipeline supplies with seaborne deliveries.

But one area where the EU will have to come up with clear guidance is on refined product origin. Although it is relatively easy to determine what is, and isn’t Russian crude. That is potentially much more difficult for refined products.

Blends of products that include Russian material may well be banned, but what about diesel fuel produced in, say, an Indian refinery that has started to process Russian crude? Is that Indian, or is it Russian? Classing it as Indian may provide relief to European buyers, but it also throws a lifeline to Moscow.

Only time will tell how that would play out in practice.

Net Impact

Finally, there’s a question: What does Europe really want? Does it want to completely stop Russian exports or does it want to stop buying them. There is a huge difference in the two missions.

If Europe just stops buying, the main impact could be a reshuffling of trade.

However, a proposed ban on insuring ships moving Russian oil suggests the EU may want to target overall petroleum sales. If that were the case, and if the steps proved successful, then Europe -- and the world’s -- challenge in replacing Russian oil would be far bigger.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.