(Bloomberg) -- Want the lowdown on European markets? In your inbox before the open, every day. Sign up here.

Europe’s unconventional experiment with negative interest rates to spur economic growth and inflation is looking like a trap.

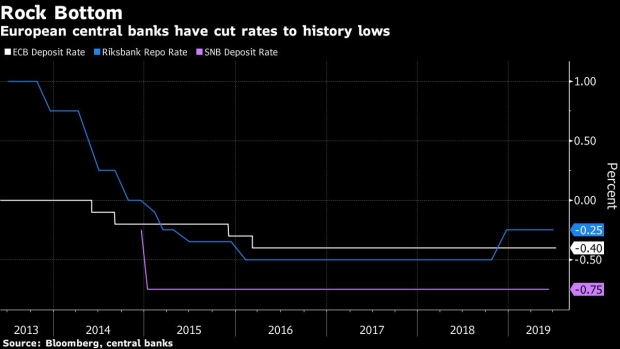

Five years into what was supposed to have been a temporary shot in the arm for the euro area, the European Central Bank still hasn’t achieved its goals and may be about to push rates even lower. Japan, Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark have also stepped over the zero bound, once seen as the lower limit for monetary policy.

With global economic growth slowing, negative rates are staying around. But the longer they persist, the louder the criticism grows. They’re blamed for weakening banks, expropriating savers, keeping dying companies on life support, and fueling an unsustainable surge in corporate debt and asset prices.

Central bankers acknowledge they’re not ideal, but they’re also resolute that their actions helped prevent deflation and support growth. That said, to say anything else would damage credibility of their primary policy tool.

The risk is that negative rates become permanently entrenched. That’s a pressing fear in banks, which can’t readily pass on the cost -- effectively a charge on their spare cash -- to their retail depositors.

“I would never say you cannot go negative, you can do everything for a short time,’’ Axel Weber, chairman of UBS and a former ECB policy maker, said in Zurich this month. “But it’s like diving into water. You can stay under water for some time, you can’t stay there forever.’’

Deutsche Bank economist David Folkerts-Landau estimates euro-area lenders lost about 8 billion euros ($9 billion) a year to the policy. Nordea Bank CEO Casper von Koskull described it as a “dangerous environment that is actually suffocating the European banking players.”

‘Peanuts’

The ECB sees it differently, saying what lenders lose on profit margins they more than recoup on volume, as low rates boost demand for credit. Executive Board member Benoit Coeure called the 8 billion euros “peanuts” and said the bigger problems are non-performing loans and technological change.

“The sector has to be healthy to transmit accommodative policy to the broader economy,” said Carl Riccadonna, chief U.S. economist at Bloomberg Economics. “Negative interest rates are not an effective policy tool if you are hamstringing the banking sector.”

Negative rates are an extreme version of the standard central bank strategy of reducing borrowing costs to spur consumption and investment.

But ultra-low rates can allow a buildup of unsustainable debt as companies and consumers finance acquisitions. The combination of high leverage and elevated valuations in areas such as real estate may also weaken an economy’s tolerance for higher rates later on, forcing central banks to stay accommodative.

They can also undermine faith in the banking system, leading to people hoarding banknotes and gold. There’s been some evidence of that in Switzerland, particularly with the 1,000-franc note, one of the world’s highest denomination bills.

The policy also throws a lifeline to unproductive “zombie” firms that crowd out resources and hurt productivity growth.

That’s one of the lessons from Japan, where rates were cut to zero two decades ago, and finally moved below that level in 2016. The nation’s never-ending policy accommodation also suggests that what the economy really needs is structural economic reforms.

European rate setters have been giving that message for years, to little response from governments. They may push the message again at a Group of Seven meeting taking place in Chantilly, France, on Wednesday.

Unlike many of its European counterparts, the Federal Reserve never went below zero with its benchmark rate. U.S. policy makers have been consistently dubious of the theoretical benefits of charging savers to keep their cash in the bank, worried in part about the impact on small banks. There’s also a question over their legality in the U.S.

But the debate is far from over. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers signed on to a paper this year that warned negative rates could make matters worse by compressing bank profits. Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan said in February he was a “skeptic” about the policy, though a paper published by the San Francisco Fed makes the case that they could have made America’s last recession less severe.

For those central banks that have implemented sub-zero rates, they’re unbowed in their view that they have worked. That’s certainly the case in Switzerland, where the minus 0.75% rate is the lowest anywhere.

“For the economy as a whole, this has been the necessary tool,” said Swiss National Bank policy maker Fritz Zurbruegg. “If we had not implemented them, we would definitely be in a worse situation than we are today.”

--With assistance from Piotr Skolimowski and Alessandro Speciale.

To contact the reporter on this story: Catherine Bosley in Zurich at cbosley1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Fergal O'Brien at fobrien@bloomberg.net, Paul Gordon

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.