May 22, 2020

Europe’s Bread Lines Get New Faces In Warning of Crisis to Come

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Giovanni Bruno, head of Italy’s food bank network Banco Alimentare, has never seen a crisis like the one sparked by the coronavirus: not only have requests for help surged by 40%, but the profile of those seeking help has changed.

Volunteers are seeing new faces among the overwhelming number of people who show up each day, unable to feed themselves. Many are workers and the self-employed who until the coronavirus lockdown had always been able to put a meal on the table.

“People tell us they are ashamed, they never needed to ask for food before,” he said. “Some call for their neighbors who don’t want to ask for help.”

The growing number of professionals in bread lines is a sign that Europe’s relatively comprehensive safety nets are fraying or failing to capture new classes of vulnerable people, even with vast new emergency aid programs. With the economy in a deep recession, and facing a slow recovery, that raises the specter of an increase in income inequality in a region that’s traditionally done a better job of tackling the problem than the U.S.

Many of the hardest hit by the sudden stop in activity are those who don’t qualify for the support that usually comes with a permanent job contract. That includes small business owners, freelancers, or temporary workers who could normally rely on a rotation of jobs in industries like tourism, hotels and restaurants.

“Even in the most developed, most comprehensive system there are significant gaps that some workers are falling through,” said Stefano Scarpetta, director of employment, labor and social affairs at the OECD in Paris.

The impact on the low-skilled and low-paid is a particular problem as many of them were merely getting by even before the crisis. They don’t have a big cushion of savings to get them through the lockdown, whether they’ve lost their job or just had a reduction in earnings.

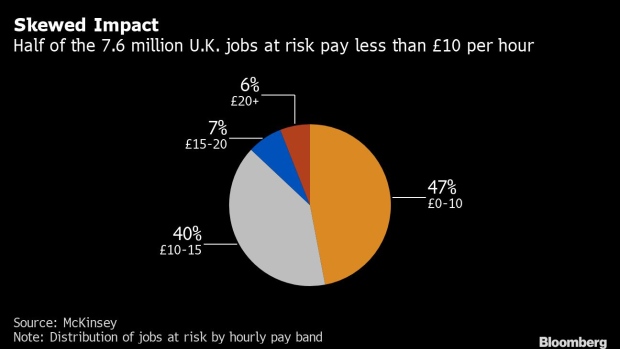

Across Europe, the rate of in-work poverty has risen since 2008 to close to 10%. In the U.K., half of the workers at risk of losing their jobs or facing reduced hours or pay are in occupations earning less than 10 pounds ($12.36) an hour -- below the target rate for the national minimum wage, according to McKinsey & Co.

And in a chilling warning, the official who oversees the U.K. national death statistics said a prolonged, sluggish economic recovery could lead to a “significant number of deaths as a result of people being pushed into poverty or into long-term unemployment.”

More Yellow Vests?

Conrado Gimenez, who runs a non-profit organization called Fundacion Madrina in Madrid, says he and his volunteers fed around 400 families a month at their food bank before the crisis. Now, they are feeding 2,500 families each day, including many waiters, cooks and other professionals.

“No crisis can compare to this one,” Gimenez said.

With the most vulnerable taking the brunt, the health crisis that’s become an economic crisis could also lead to long-term social repercussions.

That could mean a voter backlash at the polls or a rise in unrest. Less than two years ago, a fuel tax increase in France viewed as hitting poor rural workers was enough to spark the Yellow Vest protests that expanded into national riots. In Italy, young voters with limited job security helped fuel the populist Five Star Party’s rise to power.

“There is a strong risk that lots of people put their yellow vests back on for a social revolt in the street,” said Julien Damon, a sociologist and associate at Fondation Jean Jaures. “I don’t see how the pay scale can be totally transformed in a few months.”

Governments have made efforts to help, quickly putting together programs to protect jobs. France has encouraged firms to pay bonuses to those on the lowest wages and vowed to boost the incomes of front-line health workers after the crisis.

Italy’s latest 55 billion-euro stimulus package includes more tax cuts, temporary subsidies of between 600-1000 euros for self-employed workers and a special emergency income for people who don’t qualify for welfare payments.

In Spain, the government has suspended mortgage payments for some and eased access to unemployment programs for temporary workers. It’s also accelerated plans to roll out a living minimum wage this summer to help the lowest-income families.

The greater impact on temporary and gig workers partly reflects the damage to tourism, travel and leisure. That’s put staff in bars, hotels and cinemas across the region in the cross hairs. Southern Europe, with its heavy reliance on tourism, is particularly hit. In the Italian regions of Campania, Calabria and Sicily, requests for food packages are up around 60%.

The recession is also laying bare the fact that Europe’s policy makers haven’t done enough since the last crisis to close the gap between the labor market’s haves and have nots. Those on permanent contracts are harder to lay off and therefore fare better during a recession, something borne out in unemployment numbers.

Nearly 75% of the 905,000 workers who lost their jobs in Spain in March and April were on temporary contracts. Almost 16% of employees in the euro-area were on such contracts in 2019, according to the EU statistics agency Eurostat.

In France, the government put in place an unemployment insurance scheme for self-employed workers last year, but the benefits are capped at 800 euros for a maximum of six months. “By the end of the crisis, there could be a strong increase in people with zero resources,” said Eric Chevee, vice president of French small business federation CPME.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.