Nov 7, 2022

Europe’s Energy Crunch Will Trigger Years of Shortages and Blackouts

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Bills will be high, but Europe will survive the winter: It’s bought enough oil and gas to get through the heating seasons.

Much deeper costs will be borne by the world’s poorest countries, which have been shut out of the natural gas market by Europe’s suddenly ravenous demand. It’s left emerging market countries unable to meet today’s needs or tomorrow’s, and the most likely consequences — factory shutdowns, more frequent and longer-lasting power shortages, the foment of social unrest — could stretch into the next decade.

“Energy security concerns in Europe are driving energy poverty in the emerging world,” said Saul Kavonic, an energy analyst at Credit Suisse Group AG. “Europe is sucking gas away from other countries whatever the cost.”

After a summer of rolling blackouts and political turmoil, cooler weather and heavy rains have alleviated the immediate energy crisis in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and the Philippines. But any relief promises to be temporary. Colder temperatures are on the way — parts of South Asia can be more bitter than London — and the chances of securing long-term supplies are slim. The strong US dollar has only complicated the situation, forcing nations to choose between buying fuel and making debt payments. Under the circumstances, global fuel suppliers are increasingly wary of selling to countries that could be heading for default.

The center of the issue is Europe’s response to tightening fuel supplies and the war in Ukraine. Cut off from Russian gas, European countries have turned to the spot market, where energy that isn’t committed to buyers is made available for short-notice delivery. With prices soaring, some suppliers to South Asia have simply canceled long-scheduled deliveries in favor of better yields elsewhere, traders say.

“Suppliers don’t need to focus on securing their LNG to low affordability markets,” Raghav Mathur, an analyst at Wood Mackenzie Ltd. said. The higher prices they can get on the spot market more than make up for whatever penalties they might pay for shirking planned shipments. And that dynamic is likely to hold for years, Mathur says.

Damage caused by global warming, such as the devastating floods in Pakistan, is also wreaking economic havoc on emerging nations, prompting leaders at UN climate talks in Egypt this month to discuss how richer countries can help provide more support.

At the same time, Europe is speeding up construction of floating import terminals to bring in more fuel in the future. Germany, Italy and Finland have secured the plants. The Netherlands started importing LNG from new floating terminals in September. European demand for natural gas is expected to surge by nearly 60% through 2026, according to BloombergNEF.

Exporters in Qatar and the United States are now entertaining bids from European importers looking to buy fuel to fill the new capacity. For the first time, emerging nations like Pakistan, Bangladesh and Thailand are forced to compete on price with Germany and other economies several times their size.

“We are borrowing other people’s energy supplies,” said Vitol Group Chief Executive Officer Russell Hardy. “It’s not a great thing.”

Usually when there’s a short-term shortage, nations can sign long-term supply contracts, paying a fixed rate for the assurance of reliable deliveries for years. That hasn’t worked this time. Even bids for deliveries starting years into the future are being rejected.

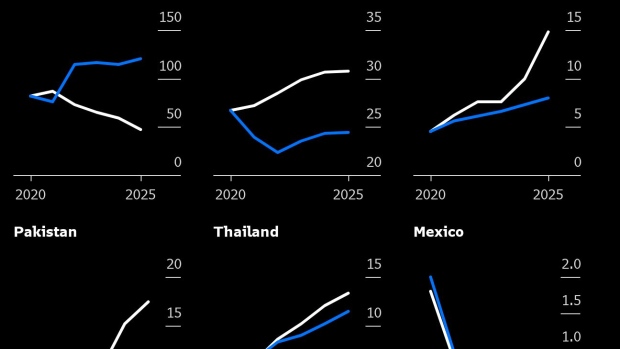

India failed in its latest attempt to lock in shipments starting in 2025. Bangladesh and Thailand essentially abandoned efforts to get contracts that start before 2026, when massive new export plants in Qatar and the US plan to start shipping fuel. Pakistan last month was unable to close an six-year deal that would have started next year, after several attempts at short-term purchases also failed.

“We’d thought the crisis would be over by the end of the year, but it isn’t,” said Kulit Sombatsiri, permanent secretary of Thailand’s energy ministry, at a briefing on Monday. If LNG prices continue to rise, he added, the government would have to consider measures such as closing down convenience stores and other high-energy businesses.

LNG suppliers fear that these nations won’t be able to pay for promised deliveries. Fuel is priced in US dollars, and a single shipment currently costs nearly $100 million. For comparison, LNG shipments averaged $33 million during the 2010s. And costs are higher still in domestic currencies because the dollar has been rapidly appreciating, adding to pressure on the countries' beleaguered finances.

Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves dropped to the lowest level in three years last month, pushing the nation’s credit rating by Moody’s Investors Service deeper into junk. Reserves for Bangladesh, India and the Philippines are at two-year lows. In Thailand, where inflation is already at a 14-year high and reserves at a five-year low, the central bank warned that the situation will worsen if the baht doesn’t stabilize soon.

Without Russian gas flowing into Europe, the global gas markets will stay tight. Spot prices will remain high, and without the ability to secure long-term supplies, developing countries may look to dirtier fuels or other partners.

Momentum behind natural gas growth in developing economies has slowed, notably in South and Southeast Asia, putting a dent in the credentials of gas as a transition fuel, the International Energy Agency said in its World Energy Outlook 2022. Natural gas is the cleanest burning fossil fuel, and emits less CO2 than coal when combusted.

The energy shortage has already brought the emerging world and Russia closer together. Russia’s been more than happy to offer fuel to Pakistan, India and others who’ve been shut out of the spot market.

“We have established contact with the Russian side. We are, of course, very much interested in procurement of LNG,” Shafqat Ali Khan, Pakistan’s ambassador to Russia, told the state-run Tass news agency. “If the rich countries take away all the LNG, what is going to happen to us?”

While China’s LNG imports have dropped overall in part because of high spot prices, the nation has increased purchases of Russian LNG at a deep discount. Deliveries from Russia to China are up about 25% so far this year, according to ship-tracking data compiled by Bloomberg.

Poorer countries may also turn to cheaper fuels like coal and oil. Or they’ll look to develop their own domestic resources. The International Chamber of Commerce-Bangladesh urged the government to move faster with natural gas exploration both on-shore and off-shore to replace expensive LNG. Critics of Pakistan’s government are asking why they haven’t tapped gas reserves in parts of the country.

“The only saving grace will be if it doesn’t get too cold,” said Shaiq Jawed, managing director at JK Group, a Pakistan-based supplier of textiles to global hotel chains. This summer, for the first time in 25 years, the company only received half of the gas it needed, he said. If it needs to, it can rely on electricity and coal-generated power. “This is the last resort, but closing down is not an option.”

For people worried about climate change and the environment, none of those are good options. Coal and oil are much dirtier than gas. The process of extracting new fossil fuels is energy-intensive and linked to increased pollution and earthquake activity.

“If natural gas is going to be beyond our means, obviously you’re looking at reverting to coal to an extent because you need the base level of electricity to be generated,” Nirmala Sitharaman, India’s finance minister, said last month. “And that just cannot be done only through solar or wind energy.”

Renewables, like solar, could provide relief eventually. Until then, high prices will do some of the work. Emerging Asia’s gas demand growth slowed “markedly” between January and July as sky-high prices dragged down consumption, according to the IEA. Thailand, the region’s top gas user, saw a 12% drop in demand over that period as high prices squeezed power sector use and falling domestic production reduced supply.

Governments will have to do the rest, rationing fuel and scheduling blackouts when there isn’t enough energy to go around.

It will take up to four years for the market to balance, said WoodMac’s Mathur. Until then, volatile prices will be the norm and, he said, “LNG will belong first to the ‘developed,’ with the leftovers for the ‘developing.’”

Countries in South America, like Brazil and Argentina, may be slightly more insulated, given investments in hydropower. Even so, Brazil’s import bill more than doubled during the first seven months of this year to $3.7 billion, the result of surging overseas prices and delays on a domestic pipeline project. If the rainy season is late this year, Brazil may need to buy time with still more LNG imports.

“We shouldn’t forget that the part of the LNG that we get, somebody else doesn’t get,” said Gunvor Group Ltd.’s Chief Executive Officer Torbjorn Tornqvist.

Meanwhile, the Philippines and Vietnam are rethinking plans to start importing LNG. The Philippines continues to delay the start of their first import terminal, while the government in Vietnam is considering cutting capacity for planned gas-fired power plants. Those projects were designed to meet surging domestic demand. Policymakers have yet to put forward an alternative.

--With assistance from Ann Koh and Patpicha Tanakasempipat.

(Adds details in 20th paragraph.A previous version of this story correctedKulit Sombatsiri’s title.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.