Dec 7, 2021

Europe Warned of National Security Risk From China Chip Advances

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China’s rapid advances in semiconductor technology pose a national security risk to Europe that requires governments to make sweeping changes to their plans to build out the chip industry, according to the conclusions of a new report.

Current European Union proposals to secure a leading-edge chip fabrication plant don’t amount to a viable strategy and “won’t suffice,” said Jan-Peter Kleinhans of the Stiftung Neue Verantwortung think tank, and John Lee, formerly of the Mercator Institute for China Studies.

The EU is working on a bloc-wide semiconductor strategy that aims to ensure access to what have become crucial components of digital life amid chip supply-chain shortages and the geopolitical challenges of a hardening U.S.-China tech rivalry.

A key target of the EU Chips Act, which is to be formulated by mid-2022, is for the bloc to account for 20% of global semiconductor market share by 2030, in part by designing and manufacturing its own cutting-edge chips.

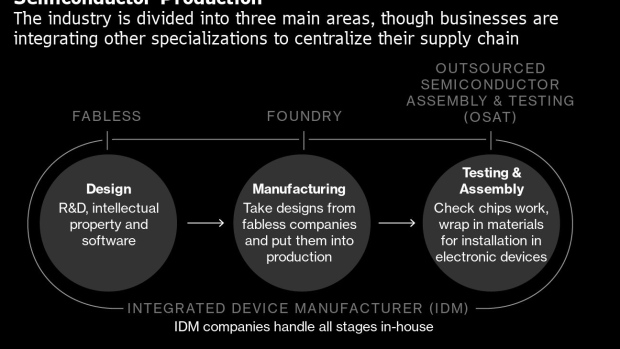

Kleinhans and Lee instead urge the EU to pour funds further down the supply chain, focusing on assembly, testing and packaging alongside encouraging local startups and universities to focus on chip design. The pair also called for the region to get a better grasp of its supply chain to avoid further bottlenecks and shortages.

Neglected But Crucial

These areas “are neglected in current debates but crucial to Europe’s technological competitiveness and security,” they say in a joint paper to be released in Berlin on Wednesday.

As project director of Technology and Geopolitics at the SNV, Kleinhans’s research is closely watched for his analysis of the political dimension of the chip industry, while Lee is a China expert who worked for Australia’s foreign ministry and defense department before becoming a senior analyst at Merics.

Over the past two decades, Europe has become increasingly dependent upon China in various steps of the value chain for computer chips, the basic building blocks of technologies from home appliances to self-driving cars. That poses potential risks in terms of national security, technological competitiveness and supply chain resilience, according to the report.

So far, the EU and member governments including Germany and France have responded by championing plans to attract a “fab” capable of producing the most advanced chips. Currently only Taiwan and South Korea have that capability, which is why the U.S. and Japanese governments have offered billion-dollar subsidies to lure Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and Samsung Electronics Co. to set up plants in their respective countries.

Chip Design

While subsidizing the construction of such fabs is necessary, the EU needs to move away from “a narrow set of policy prescriptions” and enter strategic partnerships with east Asian economies that play a critical role in the value chain, including Taiwan and South Korea, but also Japan, Singapore or Malaysia, the authors write.

One area in which they advocate “substantially investing” to counter dependency is chip design, particularly through improving conditions for startups, small and medium-sized enterprises and research institution spinoffs.

Chip design is gaining in importance as semiconductors become increasingly specialized. While the U.S. is still dominant in the field through companies including Nvidia Corp. and Qualcomm Inc., they are “highly dependent” on sales to China for continued profit growth and research and development investment, according to the White House Supply Chain review published in June.

China is meanwhile making inroads with “hyperscalers” such as Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu increasingly designing their own chips for tasks including artificial intelligence and cloud computing, according to Kleinhans and Lee.

Military Capabilities

That burgeoning design capability has national security implications since it “gives China’s military access to potentially more powerful and efficient chips,” they write, citing the use of supercomputers to simulate missile trajectories.

What’s more, U.S. sanctions have a limited impact on China’s ability to design cutting-edge chips, merely displacing talent to other companies.

Another key area of the researchers’ focus is chip assembly, test and packing. Such “back-end” manufacturing used to involve cutting out chips from a wafer, testing and then mounting them. Labor intensive and low value, it was mostly outsourced to Asia: more than 60% of global capacity is based in Taiwan and China. Now, however, advanced packaging is increasingly important to developing high performance and energy-efficient chips.

Yet with less than 5% of global capacity, Europe, like the rest of the world, is already heavily dependent on China for back-end manufacturing.

This step also provides the most opportunities for a malicious actor to compromise a chip, write Kleinhans and Lee. “Expanding Europe’s wafer fabrication does not alleviate the national security threat if those wafers are then shipped to China for assembly, test and packaging,” they add.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.