Aug 13, 2019

Fears of Argentina default loom large as traders dump everything

, Bloomberg News

How investors should play Argentina's political uncertainty

Argentina is once again on the cusp of a full-blown financial crisis.

In the wake of President Mauricio Macri’s stunning rout in primary elections over the weekend, investors dumped its stocks, bonds and currency en masse, leaving much of Wall Street wondering whether the country was headed for yet another default.

The upset, widely seen as a preview of October’s presidential vote, threw the doors open to the very real possibility a more protectionist government will take power come December and unravel the hard-won gains that Macri made to regain the trust of the international markets. It deepened worries his populist opponent, Alberto Fernandez, and running mate, former president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, will try to renegotiate its debts as well as its agreements with the International Monetary Fund. The country has billions in foreign-currency debt due over the coming year.

“The market is starting to price in default,” said Edwin Gutierrez, the London-based head of emerging-market sovereign debt at Aberdeen Asset Management. “The market is unwilling to give Fernandez the benefit of the doubt.”

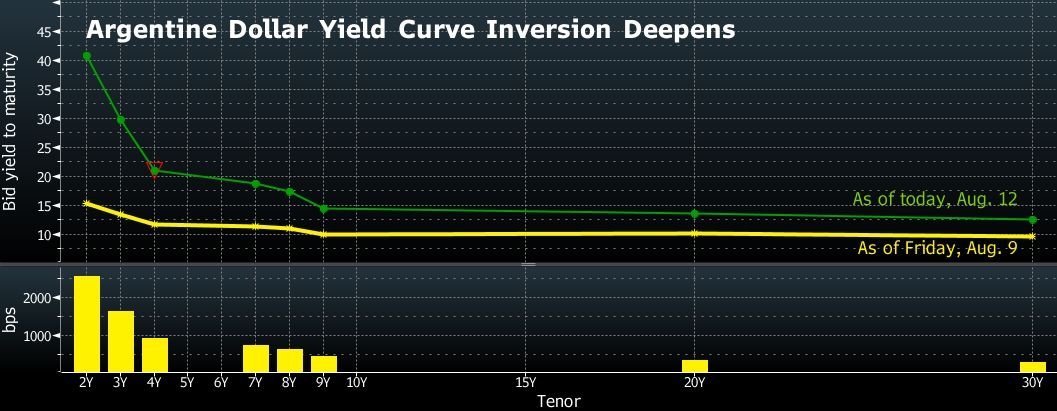

Credit-default swaps showed that traders were pricing in a 75 per cent chance that Argentina will suspend debt payments in the next five years. On Friday, the likelihood was just 49 per cent. Its dollar-denominated government bonds lost roughly 25 per cent on average, pushing down prices to as low as 55 cents on the dollar. Yields on shorter-maturity notes soared past 35 per cent.

The peso tumbled as much as 25 per cent to a record-low 60 per dollar Monday and the Merval stock index lost the most ever in intraday trading. Other markets were largely unaffected by the turmoil, with the Brazilian real and Mexican peso each weakening about 1 per cent.

Expected to trail his opponent by just a few points, Macri was instead pummeled at the polls Sunday, with voters giving Fernandez a 15-point lead. The sudden shift in voter sentiment shocked foreign investors and Argentines alike, who have suffered through years of high inflation, economic malaise and political division.

Argentina has a long history of fiscal crises and it was only in 2016, under Macri, that the country put its most recent sovereign default behind it. Argentines still remember the 15-year default saga and deep recessions following a record default in 2001.

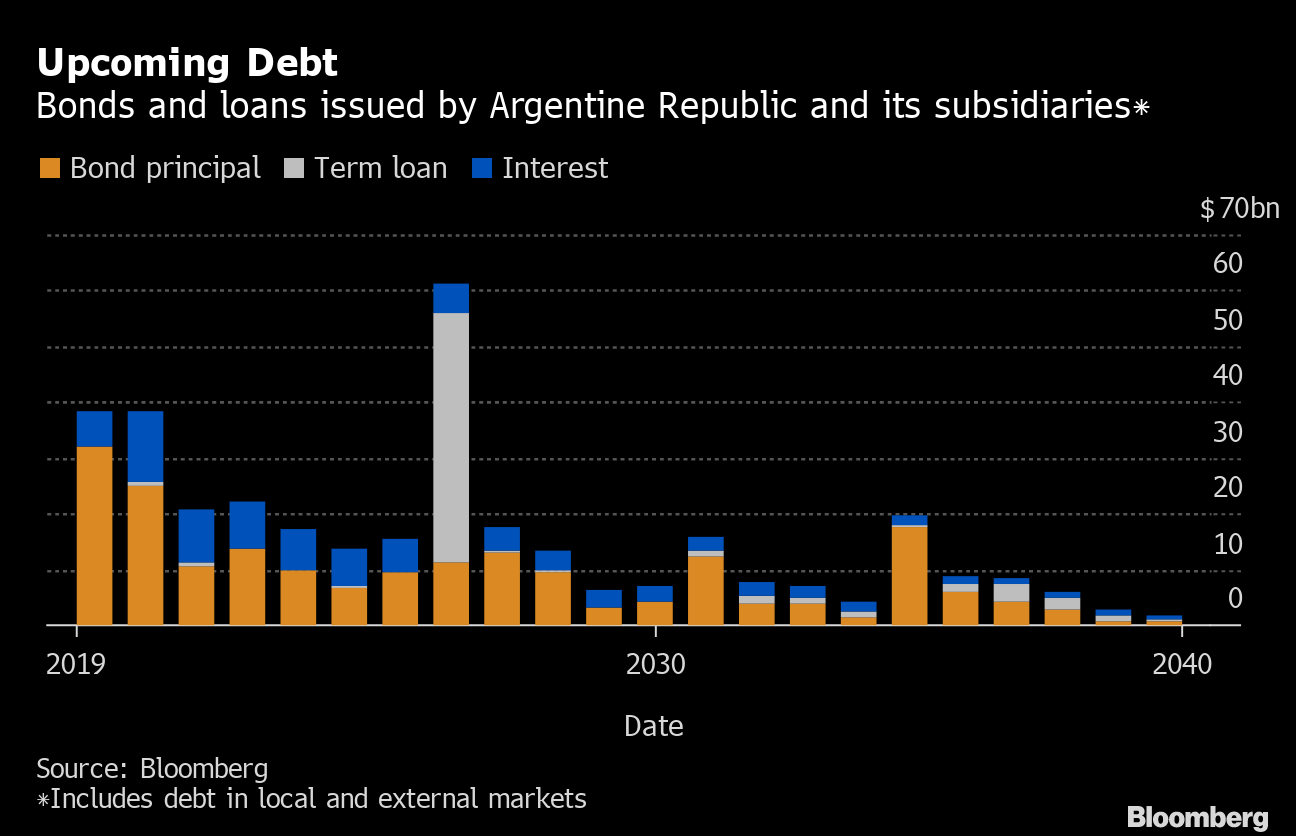

The government and its subsidiaries currently have US$15.9 billion in debt payments denominated in dollars and euros due in 2019, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. There are another US$18.6 billion in bond principal, loans and interest payments issued in pesos.

Investors are fearing the worst. Fernandez was cabinet chief under former President Nestor Kirchner, while his vice presidential pick, Cristina Kirchner, led the republic for eight years before Macri came to power. During her time in office, Argentina was marked by currency controls, data manipulation and protectionist policies on trade to protect national industry. And, of course, it was also punctuated by another default that made the country an international pariah for years.

“The hopes of Argentina becoming a sustainable, well-functioning economy have been shattered for now,” said Patrick Wacker, fund manager for emerging-market fixed income at UOB Asset Management Ltd. in Singapore. “I do not see a silver lining in the results.” The company expects to cut its exposure further on Argentine bonds once prices stabilize, he said.

“It is going to be an extremely tough period for Argentinian assets,” said Marcin Lipka, a senior analyst at brokerage Cinkciarz.pl in Zielona Gora, Poland. “Without moderation of the Fernandez duo and regarding increasing expectations of another fight with the IMF, I would not exclude that peso could hit 100 level to the dollar in the next 12-month period.”

Lipka, whose outlook on Latin America currencies has been among the most accurate since the second quarter of 2018, said a rate of 100 pesos per dollar wasn’t his base case, but that he does expect extreme volatility in the coming weeks. There’s a risk the currency will be doubly hit amid liquidity issues, capital outflows and string inflation pressure.

Luiz Ribeiro, the lead money manager for Latin American equities at DWS Group in Sao Paulo, said he will probably cut his exposure to Argentina in half. His Latin American equity fund outperformed 92 per cent of rivals in the past year after building up holdings in Argentina amid expectations of political continuity.

“What we are pricing right now is radical change in economic policies,” he said in an interview. Still he’s staying overweight relative to the benchmark as “Alberto Fernandez could come up with more moderate speech, which I think is possible given the kind of turmoil we see in the market right now.”

It’s also possible, though would be difficult, that Macri could come back as the Oct. 27 election approaches, he said.

“If Fernandez comes out with some market friendly comments (especially on the IMF front) and/or a credible economics team, this would certainly help the sentiment,” said Esther Law, senior portfolio manager for emerging-market debt at Amundi Asset Management in London. “There is a chance for this but it is difficult to predict the timing.”

In a press conference Monday, Macri said he still has a shot to reverse the trend in October and that his economic team is working on measures to address voter concerns on the economy. He also said that the market and international community lack confidence in Fernandez and the opposition as evidenced by the selloff.

While the market was hoping for Fernandez to give some words of encouragement to investors who are desperate to know his government plans, he made no apparent overtures during his victory speech on Sunday.

On Monday, he told a local radio network that the securities regulator should look into information shared late last week that prompted a rally ahead of the vote.

He suggested that the market look to Macri for answers rather than to him and that the reaction shows how investors react when they feel they’ve been “ripped off.”

--With assistance from Tomoko Yamazaki, Alex Nicholson, Ney Hayashi, Felice Maranz, Justin Villamil, Lilian Karunungan and Yumi Teso.