Feb 11, 2022

Fed Is Slamming the Door on Pandemic Era of Dirt-Cheap Credit

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- For much of the past two years, money managers were handing out credit to just about anyone that asked for it: Tech startups with no profit. Cruise companies struggling to navigate a pandemic. Retailers that rely on fading malls.

But in less than two months, the carefree days of ultra cheap credit have shown signs of coming to an end. Central banks around the world that pumped trillions of dollars into markets to keep economies afloat are now rushing to scale back the liquidity and fend off inflation. Those efforts could be hastened after U.S. Labor Department data on Thursday showed higher-than-expected price increases in January.

Across debt markets, borrowing has gotten harder for the riskiest companies and more expensive for even the most creditworthy. Orders for new U.S. investment-grade notes are dropping. Rogers Communications Inc., a Canadian wireless company, last week scaled back its ambitions on a $750 million bond offering that was initially contemplated at $1 billion, and ended up paying more interest than it expected, according to a person with knowledge of the deal. Ion Analytics, a software and consulting firm, withdrew a junk debt sale in January. Asset-backed securities offerings are taking a few days longer to close.

Cheap credit is hardly gone. There are still pockets where investor demand remains intense, most notably in leveraged loans, and even in investment-grade corporate bonds, money managers will still sometimes pile into deals. Yields have risen but are generally in line with or even below the average of the last decade, which has broadly been a period of easy money.

But as the Federal Reserve and other central banks get ready to mop up excess money in the financial system, companies and other borrowers are seeing the difference. And banks are finding that debt underwriting is a little harder, which could weigh on profit and ultimately trading revenue as well.

“There’s demand, it’s just not the overwhelming demand that we saw last year,” said Matt Brill, head of North America investment grade debt at Invesco Ltd. “You still don’t know what the uncertainty of the Fed is going to bring, so I think people are just being more cautious all around.”

The Fed is expected to start lifting interest rates by as much as half a percentage point as soon as March, the first increase of that magnitude since 2000. Money managers buying bonds now have to accept the real risk of their securities losing even more value than they already have, and losing it soon.

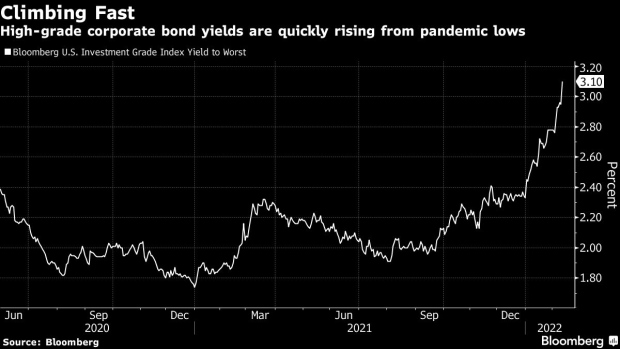

High-grade corporate bonds have lost 5.5% this year through Thursday’s close, performing worse than even U.S. equities, as yields on the average note have risen to 3.1% as of Thursday from 2.33% at the end of last year. That’s right around the average since February 2012. Even for asset-backed securities that rarely see big price movements in short periods of time, such as those tied to auto loans, spreads widened 0.08 percentage point last week.

With more potential losses, investors have been pulling money from bond funds. Junk bond funds have had outflows for the last five weeks, a sum of money totaling more than $13 billion. Municipal bonds saw nearly $3 billion withdrawn in the week ended Feb. 2, one of the largest on record, followed be a small inflow in the latest week, according to Refinitiv Lipper US Fund Flows data.

Falling Orders

In investment-grade company debt, investors this year have placed orders for just around 2.4 times as many bonds as there were notes for sale, on average, compared with 3.1 times at the same point last year and four times for all of 2020, according to data compiled by Bloomberg News. Companies are having to pay a bit more too, with the average borrower paying a yield that is about 0.05 percentage point higher than its existing debt, compared with yields a touch lower than existing debt at this point in 2021.

These figures are only gloomy by the standards of the post-pandemic world. In 2019, for example, companies sold bonds at yields averaging 0.04 percentage point higher than their existing debt.

But lower demand comes even as high-grade bond sales broadly have slowed down this year. Companies have sold about $174 billion of the notes this year, down about 7% from this point in 2021.

“The fulcrum has slanted in favor of investors in the new issue market,” said Jimmy Whang, head of credit and municipal fixed income at U.S. Bancorp, overseeing underwriting, sales and trading.

In the $4 trillion market for municipal bonds, the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority and the New York City Transitional Finance Authority saw weak demand for deals last month. The bonds overall lost 2.7% of value in January, their worst month since March 2020. Market participants were looking to sell $1.2 billion of the bonds in the secondary market on Thursday, an eye-popping amount, compared to the one-year average of about $600 million, according to a Bloomberg index.

Among asset-backed securities, sales processes are slowing down. While typically ABS transactions are announced on Monday morning and are sold by Tuesday or Wednesday, now it might take until Thursday or Friday.

There are still plenty of ABS offerings getting sold. Sales this year through Wednesday have topped $30.6 billion, exceeding the $27.7 billion seen at that point last year. And 2021 as a whole was a record. But there’s no question that selling these deals is harder, according to dealers and investors.

“Deals are a little less oversubscribed, and they’re taking a bit longer to get done,” said Nick Tripodes, a portfolio manager in structured credit at Federated Hermes. “If you look at the rising-rate environment, bonds are getting beat up across the board.”

Leveraged Loans

One of the few parts of the market where demand is still strong is in floating-rate debt in general, especially for leveraged loans. Investors have poured at least $1.3 billion into funds that invest in U.S. leveraged loans for each of the last five weeks.

Even so, issuance is falling, totaling about $79 billion so far in 2022, compared with around $131 billion at the same point last year. With strong demand and lower supply, loans have gained about 0.4 percent on a total return basis, compared with a 3.4% decline for junk bonds.

There is a more than $100 billion pipeline of leveraged buyouts to finance in the U.S. and Europe, and although the plan was always to split it between bonds and loans, now the mix is shifting more heavily in favor of loans.

When McAfee Corp., a maker of computer antivirus software, needed to get debt financing for its leveraged buyout, it had planned to sell about $3.3 billion of fixed-rate bonds and borrow $5.7 billion in the loan market. Last week, it instead borrowed $2 billion in the bond market and got the rest in the U.S. dollar and euro leveraged loan markets.

“If you’re a banker, you just follow the path of least resistance to syndicate and sell these securities, and the loan market has had monstrous appetite,” said Brian Juliano, head of U.S. bank loans at money manager PGIM Fixed Income. “I’ve had more calls with investors with interest in loans this year over, let’s say, the past six months, than I have over the past 15-plus years in my career.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.