Sep 23, 2022

Fed’s Hawkishness Casts Doubt on Bank of Canada’s Soft Landing

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The Federal Reserve’s efforts to step up its fight against inflation will cast doubt on the Bank of Canada’s ability to limit its own interest rate hikes.

At a decision Wednesday, Chairman Jerome Powell signaled Fed officials are poised to increase borrowing costs by more than expected, and are willing to tolerate much slower growth in the process.

It’s an increasingly foreboding outlook for the US that raises questions about whether Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem will be able to pull off the soft landing that many analysts still expect.

Canada is seen having both faster growth and lower interest rates over the next three years -- a peculiar mix of economic outcomes that assumes the country is more buffered from global headwinds -- including a potential US recession -- but won’t face the same pressure to match the Fed higher.

Short-term money markets are betting the Bank of Canada will stop its hiking cycle at about 4%, versus a Fed benchmark rate seen peaking at about 4.6%, and remain below US short-term rates for at least another three years.

That’s even as the Canadian economy is projected to expand at a faster pace than the US. According to Bloomberg surveys of economists taken before the Fed decision, growth is expected to average 2.1% in Canada between 2022 and 2024, versus 1.4% in the US.

“The market has the relative Fed versus Bank of Canada narrative upside down,” Derek Holt, an economist at Bank of Nova Scotia, said by email Thursday.

Historically, when Bank of Canada rates have fallen below those at the Fed, it’s typically not coincided with a relatively stronger Canadian growth picture. That suggest markets may be underestimating how high Macklem will have to go, or overestimating Canada’s capacity to grow.

To be sure, higher commodity prices are giving Canadian incomes a stronger tailwind, which helps explain the growth outperformance but not why interest rates need to be lower in Canada. New government spending aimed at helping Canadians cope with the higher cost of living is adding to inflationary pressures. Higher US rates, meanwhile, are putting downward pressure on the Canadian dollar and stoking import prices further.

“Why would a commodity producer that keeps spending its riches on here-today-gone-tomorrow consumption in serial fashion be seen as facing less rate risk than a net commodity importer going into policy gridlock for the next couple of years,” Holt said.

One possible explanation is that underlying price pressures in the US are running deeper, perhaps because of a tighter labor market. Unlike its neighbor, Canada is ramping up immigration, which should in theory at least help ease pressure off wages and potentially give it more scope for non-inflationary growth.

Inflation data for August in both countries provide some support for this theory, showing weakening price pressures in Canada but escalating inflationary forces in the US.

The Bank of Canada may also be more reluctant to jack up borrowing costs given higher household debt levels in the country, though that argument suggests underlying economic weakness rather than the outperformance many analysts expect.

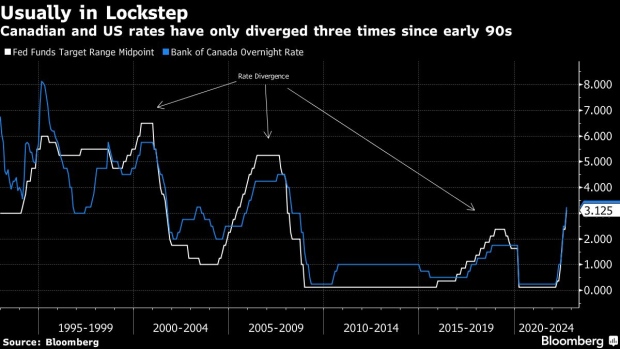

But history shows that while Canada can occasionally take a different policy stance than in the US, there are limits to this divergence -- in part because Canada’s economy is so closely linked to its southern neighbor.

Few economists are willing to project any major divergence of inflation between the two countries over the next couple of years. Immigration, meanwhile, creates its own inflationary problems in the short-term, especially in housing. And Canada’s weak productivity numbers give economists little confidence that potential growth will far exceed that in the US.

So far, the Bank of Canada has moved in lockstep with the Fed through the first half of this year. Its overnight rate is even slightly higher -- at 3.25%, versus the 3.13% midpoint for US central bank’s target range.

While Canadian policy rates have historically exceeded the Fed’s on average, it’s not uncommon for short-term borrowing costs in the US to diverge higher for a spell of time.

There have been four times since the mid 1990s that US rates have outstripped Canadian rates over a multi-year period -- often coinciding with times of global economic stress. In all but one case (1999-2000), the Canadian economy was either slightly underperforming or at best equaling US growth.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.