Jul 8, 2020

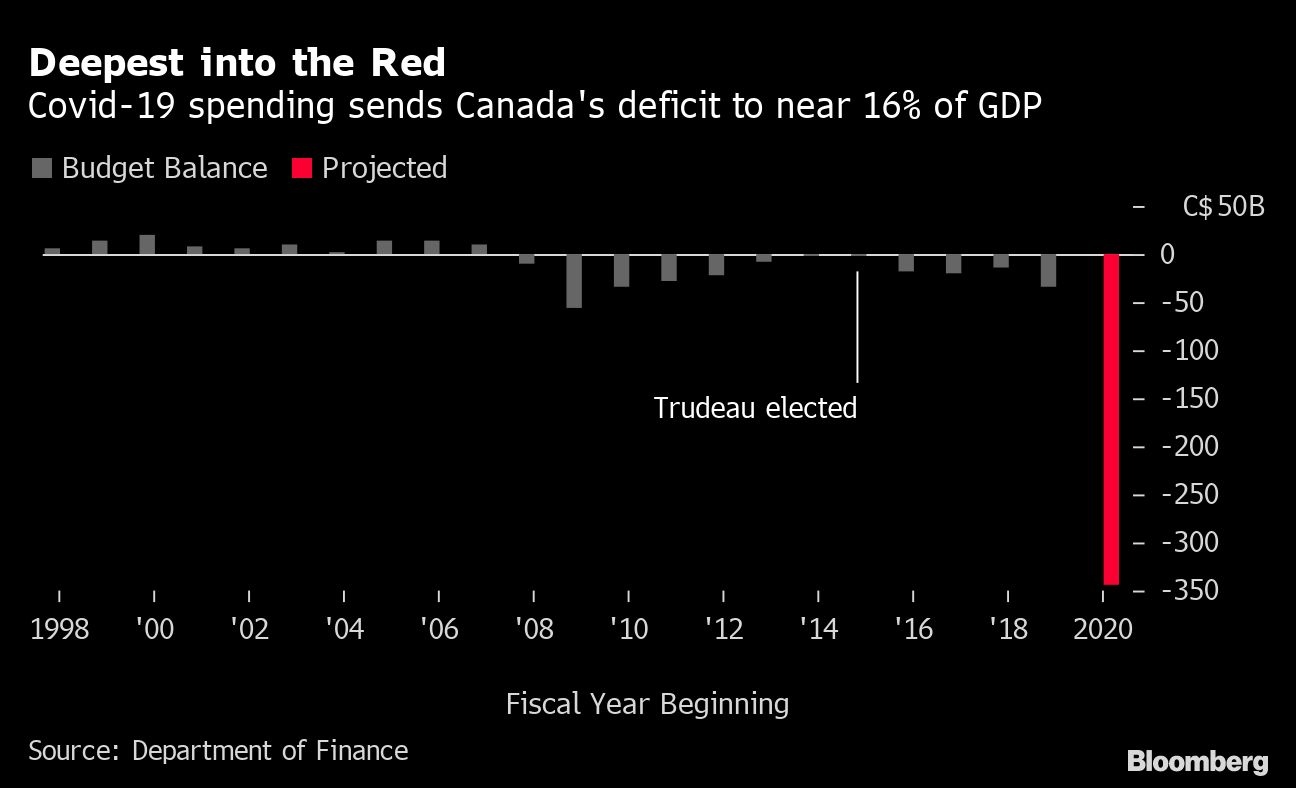

Federal deficit swells to to $343B as massive virus aid costs mount

, Bloomberg News

What's next as feds see $343.2B deficit

Justin Trudeau’s government said it will run a budget deficit equivalent to nearly 16 per cent of economic output, a level not seen since World War II, in a race to safeguard Canada from its deepest recession in almost a century.

Finance Minister Bill Morneau forecast a $343 billion (US$254 billion) shortfall in a fiscal update Wednesday that detailed the full cost of the COVID-19 crisis. Direct support to individuals and businesses will total $212 billion this year, driving spending levels to their highest since 1945. The recession has also taken a toll on revenue, which will drop as a share of the economy to the lowest since 1929.

The crisis will force Canada to issue an unprecedented amount of debt, including $106 billion in the 10-year and 30-year sectors this fiscal year. Yields rose across the curve, especially on longer-dated debt. The yield on benchmark 30-year debt increased 10.8 basis points to 1.092 per cent, according to Bloomberg data, as investors reacted to the forthcoming flood of paper.

While the announced deficit surprised on the upside -- most economists expected a deficit of just over $250 billion -- Trudeau is justifying the shortfall as the lesser of two evils. The prime minister argued the economy would be in much worse shape were it not for the government’s response, in part to thwart the need for households to take on more debt.

“We made a very specific and deliberate choice throughout this pandemic to help Canadians, to recognize that overnight people had lost their jobs,” Trudeau told reporters in Ottawa. “We decided to take on that debt to prevent Canadians from having to do it.”

While the shortfall has broad political support, it’s a dramatic departure for a country with a longstanding aversion to debt and leaves Canada with the prospect of running large deficits for years to come.

Morneau, the first finance minister to oversee a credit rating downgrade in 25 years, is under pressure to provide at least cursory assurances the government will return to a more fiscally prudent path once the coronavirus crisis has passed. “The cost of inaction would have been far greater,” he said in the prepared text of a speech to the legislature.

The government now projects debt will rise to 49.1 per cent of gross domestic product in the fiscal year that started April 1, up from 31.1 per cent last year. In his speech, Morneau didn’t provide any forecasts beyond 2020, or provide any indication of future fiscal plans other than to say Canada will continue to hold its low-debt advantage relative to other major economies. That status is facilitated by historically low interest rates, with public debt charges actually declining as borrowing costs fell.

“We, the collective we, will have to face up to our borrowing and ensure it is sustainable for future generations. Canada’s debt structure is prudent, it’s spread out over the long term, and it compares well to our G-7 peers,” the finance minister said. “And we will continue to make sure this is the case in he months and years to come.”

Debt Strategy

In his update, Morneau signaled the government plans to issue more long-term bonds in order to lock in low rates, but will first hold consultations to gauge the market’s capacity to absorb the supply. Annual gross bond issuance is planned to be about $409 billion in the fiscal year, $285 billion higher than the $124 billion issued for 2019-20.

Total market debt, which includes a ramp up in Treasury bills, will grow to $1.2 trillion from $765 billion.

Federal government spending, along with the deficit, is poised to hit all-time highs as a share of GDP outside of World War II. Program expenses will surge 69 per cent to $592.6 billion, or 27.5 per cent of GDP. That figure has averaged about 15 per cent in the past half century.

That includes a cost of $80 billion for the the main income support program -- the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, or CERB. One change in Wednesday’s documents is a top up of almost $40 billion in the government’s wage subsidy program to $82.3 billion. The numbers suggest the government anticipates to transition Canadians from the $2,000-per-month cash support beginning in September.

Revenue will drop 21 per cent to $268.8 billion, or 12.5 per cent of GDP, reflecting a sharp decline in receipts from personal income and sales taxes.

Wednesday’s fiscal update is based on an assumption the economy will contract by 6.8 per cent this year, the largest drop since the Great Depression, before rebounding by 5.5 per cent to 2021.

The deficit was initially estimated at $256.2 billion by the Parliamentary Budget Officer, the country’s budget watchdog. The discrepancy reflects lower tax revenue, an eight-week extension of CERB and the wage subsidy increase.

HAVE YOUR SAY