Oct 14, 2020

Finance industry gets pushed closer to key sustainability rules

, Bloomberg News

The accelerating climate crisis is increasing pressure on regulators and corporate executives to set universal standards for the burgeoning sustainable finance industry.

Sustainable finance has quickly become a core business for most banks and fund managers, since the transition to a lower-carbon world will require trillions of dollars of investment in renewable energy, electric vehicles and a host of related technologies and infrastructure.

But there’s a problem: the absence of consistent guidelines and definitions with which players can examine markets -- including carbon credits, ESG funds and green bonds.

Thanks to a “proliferation” of varying standards, incorporating company ESG disclosures into conventional regulatory filings and frameworks has been difficult, said Christine Kung, head of international affairs and sustainable finance at Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission.

Investors can’t get comparable and consistent disclosures when making decisions, and there are no globally consistent definitions and taxonomies, Kung said during a briefing hosted by Natixis Investment Managers.

“The good news is that regulators are working together to address these challenges,” she said Wednesday.

The push for more transparency comes as total green bond issuance exceeds US$1 trillion, and a similar amount of money sits in ESG-focused funds.

Financial companies and market authorities must collaborate on a universal framework, said Kevin Stiroh, executive vice president and head of the supervision group at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

“The financial risks of climate change are part of our core risk-management perspectives,” said Stiroh, speaking on a panel discussion hosted by the Institute for International Finance (IFF).

“It’s absolutely important that as a regulatory community, we harmonize and coordinate with international bodies across the globe,” said Rostin Behnam, commissioner of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, speaking at the IIF conference. “We don’t have to reinvent the wheel, but there needs to be more specificity, there needs to be more questions asked and more work done so we can have standard, reliable, common terms and common information.”

Candido Bracher, chief executive officer of Sao Paulo-based Itau Unibanco SA, said that when it comes to corporate claims made under the banner of environmental, social and corporate governance, calls for differentiating between what’s “green” and what’s not have been getting louder.

“We should make a move toward having this standardized in one single measurement, one single regulation, which would make it easy to understand and easy to deal with,” Bracher said.

Daniel Klier, global head of sustainable finance at HSBC Holdings Plc, agreed, adding that the fast pace of ESG adoption makes promulgating a coherent set of rules all the more important.

“We’ve seen so many large multinationals using this crisis to change their business models,” Klier said. “Look at the big oil and gas majors, technology companies, transportation companies.”

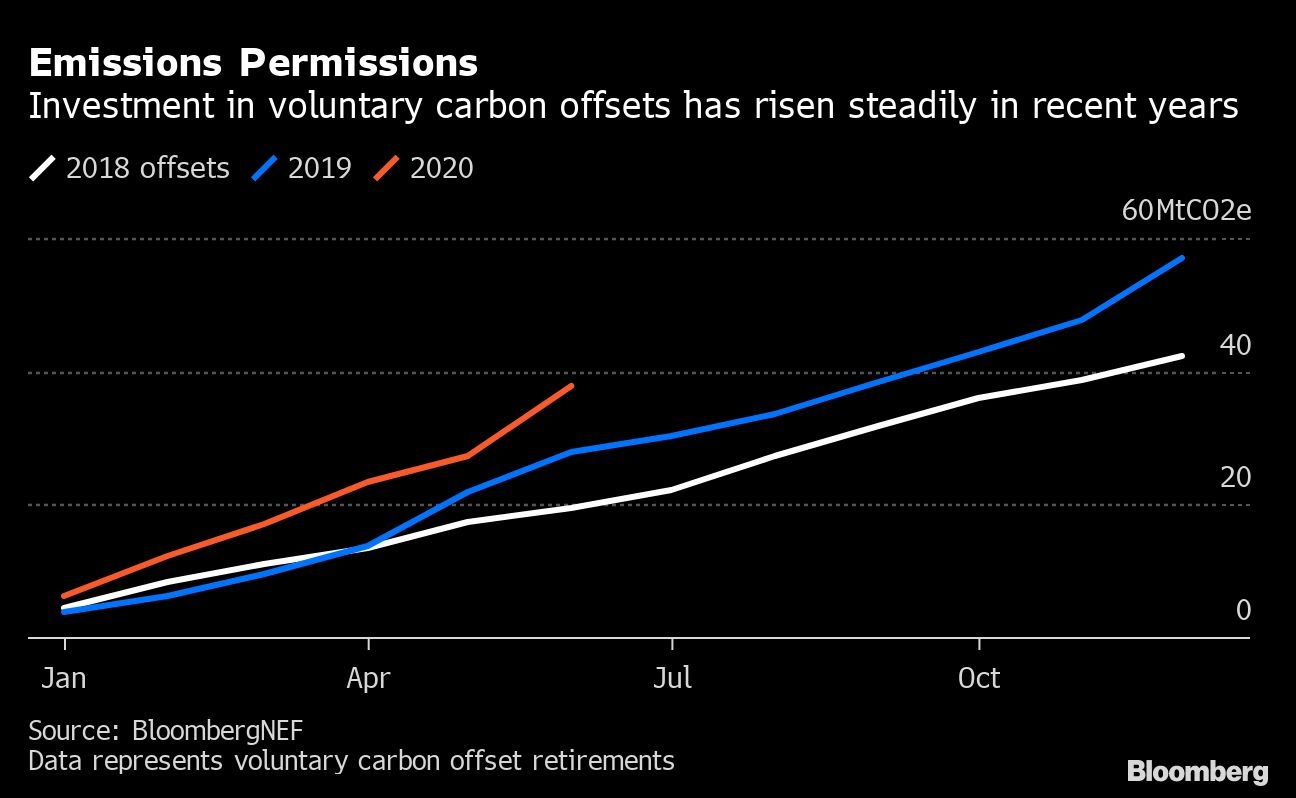

Former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney said one of his main focuses is achieving clarity in the market for carbon offsets, which can be built into something much larger to help achieve net-zero global emission targets.

Carbon offsets are used by individuals and companies to compensate for their carbon footprints. Each credit is supposed to be backed up by activities that reduce emissions, like forest conservation or the promotion of cleaner-burning wood stoves. But those projects are so varied that it’s difficult for buyers to determine the value of carbon saved from different initiatives.

It’s also not clear how much money actually goes to the pollution-saving pursuit and how much goes to the broker that sells the offset.

While “complex,” the market will be “a very major component” of the climate solution, Carney said during an IIF panel.

Standard Chartered Plc CEO Bill Winters, who also spoke at the IIF conference, is chair of an industry task force looking to boost credit offsets. The group, which has more than 40 members including BP Plc, Royal Dutch Shell Plc and Unilever NV, estimates the market needs to grow by between 15 and 160 times in order to meet the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The carbon offset market is currently regulated by non-governmental organizations and carbon registries – some of which are taking steps to set standards. But Winters has said tougher rules are needed to make it easier for regulators to be consistent and transparent around pricing and trades, similar to the way ratings agencies operate. Doing so could help to deliver a higher global carbon price, he said.

“We haven’t made much progress as a practical matter, and at least one big reason for that is that we haven’t harnessed private markets to the fullest extent,” Winters said Wednesday.