Mar 19, 2023

Finnish School Children Solve This Climate Puzzle Every Year. Can You?

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Every year, hundreds of teenagers in Lahti, Finland, play a game.

Instructors pull out a large board with a series of squares, each labeled with a climate-friendly action. “I will reduce the energy of doing laundry,” reads one. “I will buy items secondhand or recycled (90% of purchased items),” goes another. “I will favour organic food.” “I will try a vegan diet (12 months/person/year).” “I will favour sustainable services.” The size of each square corresponds with the impact of the action it outlines; the square about eating organic, for example, is less than a tenth the size of the one about going vegan.

This is the Climate Puzzle, a board game developed by Finnish sustainability company D-mat Ltd.and purchased for Lahti’s schools to help students learn to live more sustainably. The game uses emissions data from “1.5-Degree Lifestyles,” a study that D-mat Chief Executive Officer Michael Lettenmeier helped write, which calculates how much carbon each person can emit to keep global warming below the 1.5C threshold outlined in the Paris Agreement. Numerically, the report suggests an individual carbon budget of 2.5 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per person per year by 2030. Practically, that means many people would need to dramatically change how they travel, eat and vacation in an ever-warming world.

“This puzzle means that we have a whole box of different options to decrease carbon footprints,” Lettenmeier says. His ideal outcome is for players to pick the right squares for the board and then try to implement those behaviors in their real lives.

Crunching the numbers

In 2015, world leaders adopted a goal under the Paris Agreement to keep global warming below 1.5C; multiple studies soon emerged to document what that might require from governments and corporations. But Lettenmeier wanted to know what he should do personally — so he started looking into individual emissions. Eventually, he linked up with a team of researchers from Japan’s Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) to calculate how much carbon each person on Earth could emit to achieve the Paris Agreement goal.

The researchers looked at what they described as “lifestyle carbon footprints,” or greenhouse gas emissions “directly emitted and indirectly induced from the final consumption of households, excluding those induced by government consumption and capital formation such as infrastructure.” These emissions include how a person fuels their car, for example, or what products they buy and which foods they eat. The report found that by 2030, every person should be emitting 2.5 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year or less; by 2050, that drops to 0.7 tonnes.

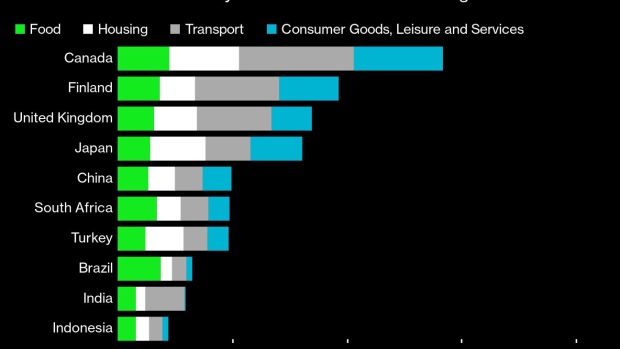

To determine how close the population is to those targets now, the researchers chose 10 countries (most from the G-20) to represent different lifestyles and levels of wealth. Using 2019 estimates, they found that the average person in just one of those countries, Indonesia, was below the 2030 carbon threshold. The rest — India, Brazil, Turkey, South Africa, China, Japan, the United Kingdom, Finland and Canada — were over budget, with the highest emitters releasing about four times the allotted per capita emissions for 2030. None of the countries studied met the 2050 target.

“We need to change our ways of living,” says Lewis Akenji, the lead author of the 1.5-Degree Lifestyle report and managing director of climate think tank Hot or Cool Institute. “But it's unclear what to prioritize.”

Akenji concedes that the report’s methodology lacks some nuance. Calculating the average emissions of any single person or country is complex, and the report relied on datasets — from governments, academic studies and international organizations like the United Nations — that offer approximations in lieu of exact figures. Per capita emissions also vary by individual, and wealthier people emit the most. Between 1990 and 2015, according to one estimate, the richest 10% of people in the world accounted for over half of greenhouse gas emissions. Lastly, while individual choices do matter, change from governments and corporations matters more, so pointing a finger at regular people comes with risks of its own.

“It’s quite a guilt-inducing area,” Akenji says. “We have to be careful to understand where individual agency comes in, collective responsibility comes in, and where policies and businesses need to take responsibility for this.”

Living the lifestyle

When Toronto-based climate writer Lloyd Alter first read about the 1.5-Degree Lifestyle in 2019, he decided to try and live it for real — for an entire year. Alter stopped driving a car and rode an e-bike instead. He cut out red meat and took just a single flight that year. He ultimately succeeded at keeping his individual emissions below the 2030 goal, and went on to publish a book about the experience.

“A lot of people said for years that personal actions don't matter,” Alter says. “Personal actions are very important.”

In 2021, his experiment caught the eye of Kate Power, a climate researcher at the Hot or Cool Institute who decided to replicate Alter’s trial for one month with 16 people across six countries. The researchers recruited friends and colleagues, yielding a sample group that was far more sustainably-minded than the average person. Still, nearly a third of participants failed to meet the emissions goal.

“It was much harder because no one else was doing it,” says Florence Miller, a study participant who lives in a village outside of London. “But if everyone else was doing it, it wouldn’t have felt hard at all.”

Lettenmeier hopes The Climate Puzzle can help more people get there. So far D-mat has sold about 150 puzzles, which now go for about $130 a pop, mostly to institutional clients who use them to run workshops. Because each edition must include country-specific emissions calculations, the company has only made puzzles for a handful of European countries, including Finland and Germany, but Lettenmeier is seeking funding to develop more versions. In the meantime, he’s been traveling Europe to present the game at conferences.“It's not only about individuals,” he says. “But individuals always can start doing something while they're waiting for the politicians."

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.