Feb 3, 2023

Food Costs Are Tumbling But Shoppers Still Face Soaring Bills

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As a rout in the price of food commodities from wheat to cooking oil deepens, the cost of products on grocery shelves continues to rise.

Almost a year on from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sent grains and other staples soaring to a record, a United Nations’ index of food-commodity costs fell for a 10th straight month in January. The longest falling streak in at least 33 years contrasts with the food inflation that’s worsening a cost-of-living crunch for consumers.

Food executives are warning of more price hikes to come, even as commodities like palm oil and dairy decline. Diplomats talk of the worst food crisis since World War II, with parts of Africa on the brink of famine.

This striking dissonance underscores the significant time lag for farmgate prices to feed through to those paid by households. Moreover, food commodities only make up a small proportion of the cost inputs for products such as breakfast cereals.

In the US, the farm level portion of food consumed at home is about quarter of the costs, and only about 5% when eating out, according to Joseph Glauber, former chief economist at the US Department of Agriculture.

Take bread. The cost of wheat accounts for as much as a 10th of the total cost of a loaf, Glauber said. The rest is driven by transporting the wheat, milling it, making and baking the bread, packaging it and stocking grocery stores, he said.

Higher energy prices are still feeding through to processing costs, workers are demanding higher wages and suppliers are pushing retailers for higher pay.

It’s “the tail-end of the energy price impact that’s still washing through,” Archie Norman, chairman of UK retailer Marks & Spencer, said in an interview last week. “And secondly, labor costs. We’ve got the minimum wage rising. That has a bearing on almost all growers, producers, manufacturers.”

Inflation has peaked but food prices have not, said Alan Jope, the outgoing boss of Unilever, which makes Hellmann’s mayonnaise and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. Food giant Nestle SA expects inflation to persist in the first half of the year with some softening after that, according Chief Financial Officer Francois-Xavier Roger.

To be sure, there are signs some prices are easing. In the US, food inflation saw the smallest increase in December in 21 months as prices for bacon, flour and fresh fruit fell. Inflation is starting to moderate, but prices are still rising, according to the boss of Conagra Brands Inc., the maker of Birds Eye frozen food and Slim Jim jerky.

“This inflation super cycle has been more significant and more persistent than I think anybody expected at the beginning,” Chief Executive Officer Sean Connolly said in an interview last month.

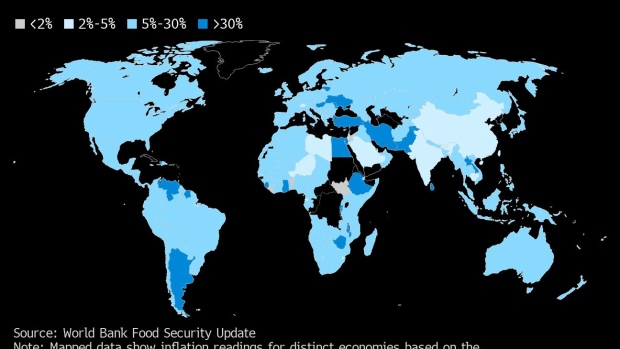

That moderation won’t console many consumers in low- and middle-income countries, which have been particularly hard-hit by soaring food inflation, the World Bank said earlier this week. A combination of shrinking foreign exchange reserves, weakening local currencies and debt pressures are undermining local economies.

And as for commodity prices themselves, there is still much uncertainty in markets, said Glauber, a research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute.

Agri-commodities and fertilizers are still historically expensive, while grain stockpiles remain tight just as extreme weather in places like Argentina and East Africa damages crop prospects, the Washington-based think tank said last week. Also rice, the backbone of global food security, needs to be closely watched.

“There are still risks,” Erin Collier, an economist at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, said in an interview. “Prices have come down but they’re still high and looking firm.”

--With assistance from Zoe Schneeweiss, Dasha Afanasieva and Deena Shanker.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.